Maryland never seceded from the Union, and therefore was not subject to the Reconstruction policies of either the President or of Congress. This meant that soothing old animosities and healing old wounds, not to mention creating a plan for a world that no longer encompassed slavery, would fall to the state of Maryland and to the localities. The war had made the fate of slavery unequivocal, but it had not provided any blueprint for a smooth transition to a new society. It soon became clear that many people who were ready, however reluctantly, to accept the end of slavery were not ready to accept changes to the social structure that slavery had supported. Nor were they ready to welcome back those who had fought against the Union.

This was the case along the mid-Maryland border. When questions of political and social democracy arose for both former Confederates and newly freed slaves in the region, it was evident that old political, social, and racial divisions had survived the war.

Return of the Soldiers

In the months that followed the end of the war in April 1865, soldiers from both sides began to return to their homes. In the mid-Maryland region, Union soldiers were welcomed with public ceremonies and celebrations. The following appeared in the July 5, 1865 Hagerstown Herald and Torch Light:

Soldiers of Washington County, We extend a cordial invitation to all of you to come to Hagerstown, on the 12th of July. The Union men of our County wish to give you a Public Welcome back to your homes. They wish to show you that they appreciate the services you have rendered our country and to join their congratulations with yours on the happy termination of the struggles for the preservation of our liberties.

In Frederick, the Frederick Examiner extended a similar “cordial greeting to the returned veterans of Frederick city and county.”

The Confederate soldiers who returned to the region received no such public reception. The Frederick Examiner made a point of comparing the return of the “eager and faithful” Union soldiers with that of the “Traitor” who sought to “tear down” the “fairest fabric of government ever created.” The Union soldier will be “taken warmly by the hand” with the gratitude of the nation, while the Confederate, “bearing the mark of Cain,” will be shunned.

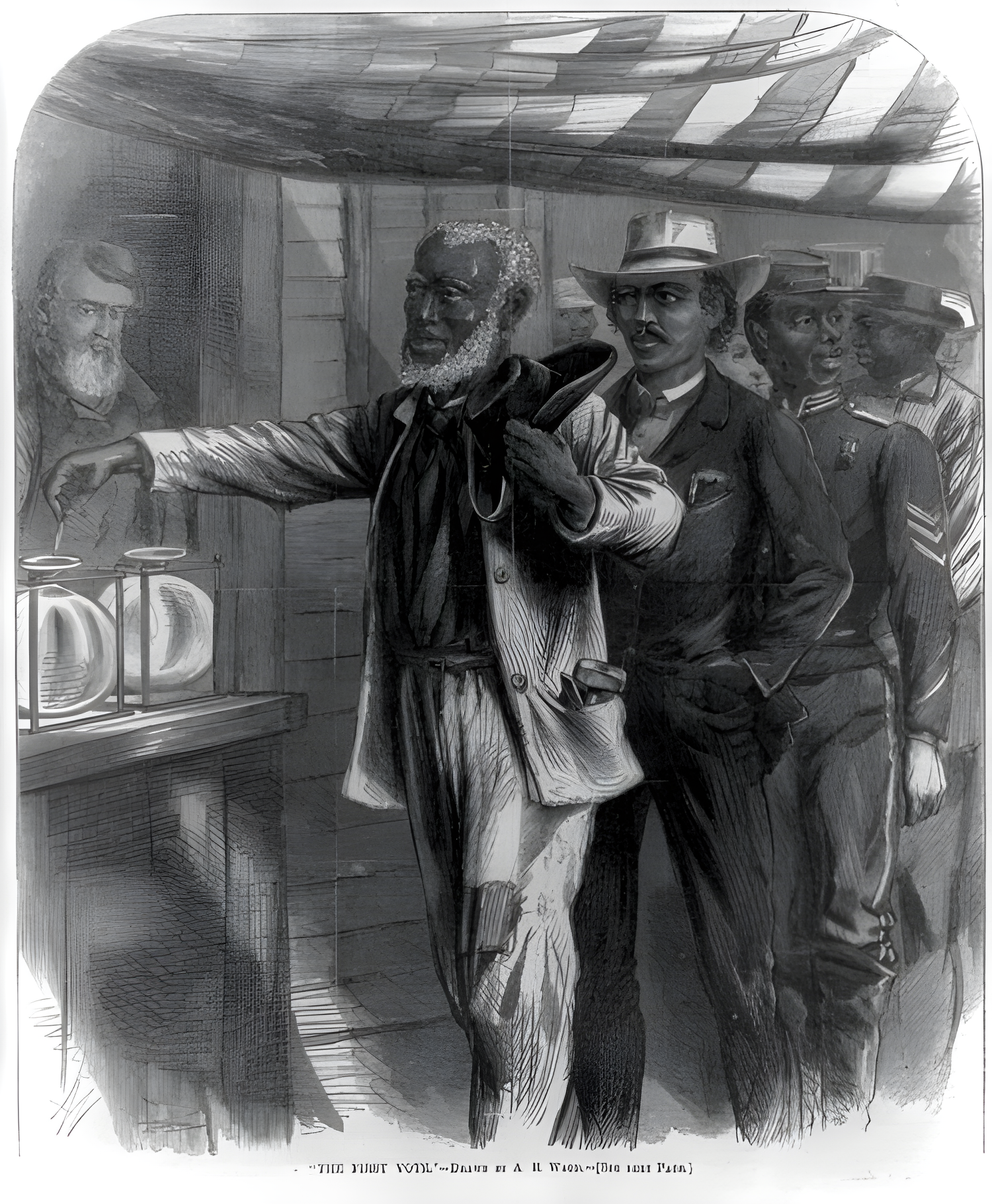

Under the terms of President Lincoln’s General Amnesty Proclamation, issued December 8, 1863, former Confederates had to report to the local provost marshal and take an oath of loyalty to the Union to avoid arrest. Frederick County held a public meeting on April 20, 1865 to consider its response to the expected return of former Confederate soldiers. There it was resolved to not molest those who complied with the terms of the President’s proclamation and who intended to live as law abiding citizens.

This was not enough for Unionists in Washington County. Since their county had suffered the most from the Confederate invasions, Washington County citizens would determine for themselves if they would permit former Confederates to live amongst them. The convention held for this purpose created a Vigilance Committee to consider the question. The Vigilance Committee announced its decision on May 6, 1865: with “all the crimes committed by them [the former Confederates] fresh in our memories,” “outlawed traitors” would not be allowed to return to the county.

The simmering rancor of some Unionists on the border, who blamed ex-Confederates for the devastating war and found their presence “insulting,” resulted in instances of citizens taking measures into their own hands. InHagerstown, former Union soldiers roughed up paroled ex-Confederates who were brave enough to return. In Boonsboro, a Vigilant Committee ordered John Wakenight, a former Confederate soldier, to leave town which, “after some parleying,” he did.

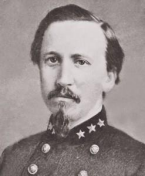

If ex-Confederate soldiers encountered hostility upon returning, the experience of former Frederick attorney Bradley T. Johnson illustrates the difficulty ex-Confederate officers had integrating themselves back into their old communities. Confederate officers above the rank of colonel were not included in the President’s General Amnesty Proclamation; they had to appeal directly to the President for a pardon. Bradley T. Johnson, who had led a military company from Frederick County to Virginia in 1861 and rose to the rank of brigadier general in the Confederate Army, fell into the category of those ineligible for the general amnesty. After the war ended, Johnson applied for a presidential pardon. Johnson’s wife and son returned to Frederick during the summer of 1865, and he himself hoped to do the same even though his property in town had been seized and sold. During that summer, however, Johnson was indicted for treason in Maryland. Months later, on March 26, 1866, he was placed under arrest and was released only after posting a $20,000 bond. Friends and supporters worked for dismissal of the charges against him. Even a former foe, U.S Army Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant, wrote a letter indicating that Johnson was among those who had been paroled during the war in an agreement between Union Maj. Gen. Philip H. Sheridan and Confederate General Joseph E. Johnston. President Andrew Johnson intervened in Johnson’s case and ordered that the charges against him be discharged and his bond released. A few months later, however, when Bradley T. Johnson came to Frederick to visit relatives and friends, it was clear that animosity and distrust from the war years remained. The reported:

Brad T. Johnson, late of the rebel army, arrived in this city, on Wednesday last. He received a warm welcome at the hands of his old friends, who feasted him in an elegant style. What a change time has wrought. A few years ago when it was announced that Bradley was approaching the city, many of our citizens scampered off to places of safety, evidently afraid of the rebel hero. Under the law, Mr. Johnson has a right to come here—and we respect the law that gives him that right, but had he not accompanied the raids which inflicted so much harm and injury upon our citizens, he could have come back with a much better face. We suggest while he is here to have his name registered. He can take the oath with as clear a conscience as some of those who applauded him whilst he wore the rebel uniform.

Ultimately, Johnson chose not to live in his native city. Instead he moved to Richmond where he practiced law and was elected to the Virginia General Assembly. Little did Johnson realize when he led a military company out of Frederick toward Virginia in early May 1861 that he would never live in his hometown again.

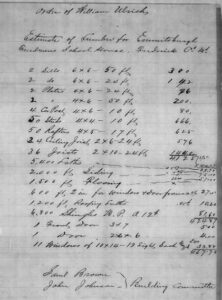

Veterans of the United States Colored Troops found a mixed reception upon their return. Within their own communities, Black veterans often played important roles in the development of local African American institutions. Many served as church or school trustees. In Sharpsburg, Wilson Middleton, who served in Co. F of the 115th Regiment, USCT from April 1865-February 1866, was among the founding trustees of the Sharpsburg “Colored” ME Church (later Tolson’s Chapel), built in 1866. In northern Frederick County, USCT veterans Samuel H. Brown and John Johnson served on the “Building Committee” for the Lincoln School in Emmitsburg. At the same time, a Frederick newspaper editorial displayed the writer’s disrespect of Black soldiers as he justified his opposition to voting rights for Black men. Published under the title “The Right of Suffrage,” the writer began:

It is a fallacy that the negro, because he is a human being, and is possessed of rights that may be affected by law, should have a right to vote. It is equally a fallacy, that because he may have served in the army, he should have this right.

Physical abuse by individuals who took issue with Black service in the Union cause occurred most often in states south of Maryland. In a particularly egregious case, Freedmen’s Bureau agent Marcus S. Hopkins reported on an incident that took place in Prince William County, Virginia in January 1866. Hopkins wrote that James Cook “was conceived to be “impudent” by a white man named John Cornwell,” noting, “this “impudence” consisted in the sole offense of saying, that he had been in the union army and was proud of it.” As Cook attempted to walk away from Cornwell, he followed and threatened him shouting, “you d——d black yankee son of a b— —h I will kill you.” Cornwell then shot at Cook, but missed, then “he beat him with the but of a revolver.” Cook managed to get away and immediately reported the incident to Hopkins.

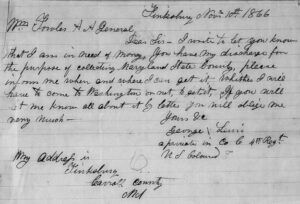

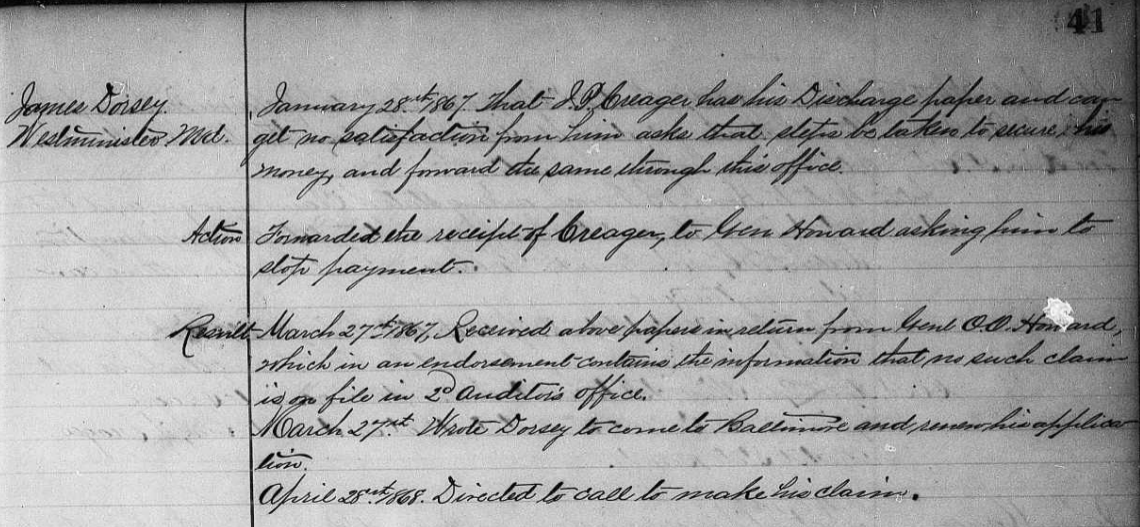

While the Freedmen’s Bureau’s presence in communities provided a layer of protection for returning Black soldiers, it was also tasked with facilitating USCT veterans’ or their heirs’ claims for payment of back pay and enlistment bounties. Maryland USCT veterans were entitled to a $300 state bounty. In the mid Maryland counties, many waited more than a year for their claims after claims agent Col. J.P. Creager reportedly took their discharge papers and collected their claims but often did not pass the bounty payments back to the rightful recipients. In Perry sent an inquiry on behalf of James H. Bryan, Elisha Caution, and Jacob L. Hatter. After submitting their discharge papers to Col. Creager, the three men said that Creager had collected their bounties but “refuses to pay the money over to the colored men.” Perry and the men he represented still had not received an answer or the money by August 1867.

Sometime in early 1868, Hatter reported to the Complaint Division that Creager had collected his Federal and state bounties totaling $400, but had sent Hatter only $200. In June 1868, the States Attorney “decided this embezzlement not to be indictable and nothing can be done in the case.” Josiah Mathews, of Unionville in Frederick County, complained in March 1868 that Creager still owed him $160 on his claim. His case was also referred to the States Attorney, who replied “the law affords no redress in this case against Creager,” and the case was closed. In all, according to a March 1868 report prepared by A.W. Bolenius, Agent for the Complaint Division, twenty-two complaints were recorded against Claims Agent Creager.

Post-war Politics

During the Civil War, the Union Party gained political control of Maryland. By 1863, however, the party had split into two factions: the Unconditional Unionists and the Conservative Unionists. Unconditional Unionists favored the immediate emancipation of Maryland’s slaves and encouraged their enlistment in the Union army. The Conservative Unionists, on the other hand, favored a gradual and compensated emancipation of slaves, encouraged their colonization outside of the United States, and opposed their enlistment in the Union army. By 1864 the Unconditional Unionists had gained the upper hand and were able to prevail at the convention that produced a new constitution for the state of Maryland. The 1864 constitution freed Maryland’s slaves without compensation to slave owners, passed a registry law that denied voting rights to former Confederates and their supporters, and based representation in the General Assembly on the white population, which had the effect of weakening still further the minority Democratic Party. When the new constitution was sent to the people for ratification, the vote revealed that significant division persisted in the state. It was approved narrowly, by only 375 votes out of nearly 60,000 cast.

Following the war, most Unconditional Unionists became Republicans, while most Conservative Unionists began to recognize common interests with the Democratic Party. By 1866 a resurgent Democratic Party gained political control of the state. Once in power, the Democrats worked at rewriting Maryland’s 1864 constitution, especially the registry law and representation based on the white population. In 1867, the state legislature abolished all provisions that would hinder returning voting rights to the state’s former Confederate soldiers. As a way to counter the strength of the Democrats, Republicans began to favor suffrage for African Americans. As a result, race would become the significant social/political issue between the two parties, both locally and statewide.

Local newspapers that had supported Southern rights before the war opposed civil rights for African Americans after the war; newspapers that had supported the Union now supported black rights. Some communities on the border had newspapers representing both positions, including Westminster, Frederick, and Hagerstown. The March 8, 1866 Westminster Democratic Advocate described plans to extend the powers of the Freedmen’s Bureau as “an extensive scheme for the education and support of the colored people at the expense of the whites.” The June 5, 1867 Hagerstown Herald and Torch Light, on the other hand, published a letter from Williamsport in which the writer encouraged people to support freedmen’s schools.

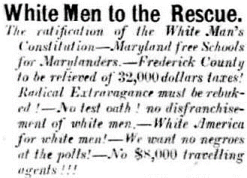

Efforts to rewrite Maryland’s Constitution also split the parties. Local newspapers that supported the Republican Party urged citizens to vote “Union” to prevent the Democrats from establishing a new constitutional convention, which, it was feared, would pass a provision to compensate Maryland’s former slaveholders from the public treasury for the loss of their slaves. With Democrats in the ascendancy, however, a new constitutional convention was authorized. The delegates drew up a document that would not only deny the vote to African Americans, but would allow blacks to be counted for the purpose of determining representation in the General Assembly. This would increase the representation of those counties that had large numbers of African Americans who could not vote, but whose white population tended to vote Democratic. After the new constitution was drawn, the Frederick Republican Citizen published a list of scheduled meetings designed to rally support for its passage. The headline included: “No test oath! no disfranchisement of white men.—White America for white men! — We want no negroes at the polls!”

The August 28, 1867 Hagerstown Herald of Freedom and Torch Light urged citizens to vote against the new constitution: “The consequence of this arrangement is that one old slave holder’s vote in Calvert county, will count as much in the election of a member of the Legislature, as the votes of three poor white men in Frederick or Washington counties.” Ultimately, at a September 18 referendum, the new constitution was approved. The constitution did give blacks the right to testify in court, but this feature was redundant since citizenship rights had been granted to African Americans by Congress in the Civil Rights Bill of 1866.

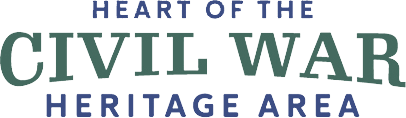

Voting rights for blacks was a contentious political issue in the border region during Reconstruction. The Democrats charged that Republicans desired suffrage for blacks not out of any concern for the African American, but only to increase their political power. Republicans and sympathetic newspapers argued that black suffrage was inevitable and that it was unjust to deny African Americans the vote. Even before the passage of the Fifteenth Amendment, the Republican Party at the state and local level worked to bring black Republicans into the political process. The Hagerstown Herald and Torch Light reported that for the 1868 Maryland Republican convention, delegations from the counties were directed to appoint one African American Republican from each county “to act as a medium of communication with the colored Republicans of the several counties, and to co-operate with the colored members of the Executive Committee in all matters affecting their people.”

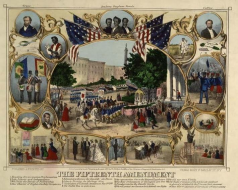

The debate over African American suffrage formally ended in 1870 with the passage of the Fifteen Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, which decreed that voting rights could not be denied to one “due to race, color or previous condition of servitude.” This did not mean that all attempts to exclude African Americans from the political process ended, but with their right to vote affirmed in the Constitution, African Americans in Frederick and Washington countiesheld celebrations to salute their new rights. Those, opposed to the idea, sought to exploit the new amendment for political gain. In a stump speech, Democratic congressional candidate John Ritchie of Frederick declared that he did not want any blacks to vote for him. This ploy backfired for Ritchie. The Middletown Valley Register predicted that black registration in the congressional district would total about 3,300, whose votes against him would effectively deny Ritchie the seat. Indeed, in the 1870 election, another Democratic candidate—not Ritchie—won the contest.

Representative Francis Thomas, former governor of Maryland and originally from Petersville in Frederick County, was the lone representative for Allegany, Washington, Frederick, and Carroll Counties in the U.S. House following the war. By 1867 he was the state’s only Republican in Congress. In September 1866 a writer to the Frederick Republican Citizen pointed out that Thomas’ voting record included votes for the Civil Rights Bill of 1865, the bill that created the Freedmen’s Bureau, and the bill that allowed black suffrage in the District of Columbia. The author added: “He is in fact, the black man’s candidate; how then can white men trust him for Maryland?” In another column, the newspaper warned that hundreds would not vote for him as a result. Thomas survived these political attacks and served in Congress through 1869.

Some newspapers tried to draw line between support of suffrage rights and support for the racial equality. The Frederick Examiner, for example, advocated in favor of black suffrage: “As for social equality, that is a question of ethics and not of politics. Political equality will not necessarily lead to social equality.” The Frederick Republican Citizen predicted that those who support black political equality will next support social equality, which it found offensive.

Democratic politicians and newspapers occasionally expressed the real reason for their opposition to African American civil rights: social equality would lead to an “amalgamation,” or a blending, of the races. The Westminster American Sentinel countered: “The less they say about ‘negro equality’ the better, for it is a fact that cannot be denied, that the immense number of mulattoes, quadroons, octaroons, &c., at the South conclusively show that something more than social equality has existed between the chivalry and colored people. These rampant ‘white men’s’ organs would do well not to slander their own family connections.”

In the 1867 legislative session, the Maryland General Assembly considered a bill that would have made fornication between a black man and a white woman a crime. In order to expose the hypocrisy of the law, an opposition legislator proposed an amendment that also would have made fornication between a white man and a black or mulatto woman a crime. The amendment was defeated, but the original measure was passed. The Hagerstown Herald of Freedom and Torch Light responded: “The people of Maryland have been told that the Union party is in favor of negro equality, “miscegenation,” &c., and that the only advocates for the purity of the Caucasian blood were the pro slavery champions and rebel sympathisers. . . . They cry out against the horrid crime of mixing the blood of the two races, and yet refuse to protect its purity by the power of the law and its avenging judgments. White men have already given to our State a population of 30,000 mulattoes.”

The people of Maryland have been told that the Union party is in favor of negro equality, “miscegenation,” &c., and that the only advocates for the purity of the Caucasian blood were the pro slavery champions and rebel sympathisers. They cry out against the horrid crime of mixing the blood of the two races, and yet refuse to protect its purity by the power of the law and its avenging judgments. White men have already given to our State a population of 30,000 mulattoes.

Emancipation

The most immediate result of the Maryland Constitutional Convention in October 1864 was the emancipation of Maryland’s remaining slaves. The U.S. Census of 1860 recorded nearly 90,000 slaves in the state, including over 5,000 in mid-Maryland. By 1864, that number had been greatly reduced by African Americans who had simply left their farms and by others who had joined the Union Army or found other employment with military forces. Freedom for the enslaved was reiterated in 1865 when the Thirteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution abolished slavery across the nation.

One Washington County owner, Otho Nesbitt of Clear Spring, recorded his reaction in his diary the day after emancipation took effect:

Nov. 2, 1864– I told the negroes that I had nothing more to do with them, that they were all free, and would have to shift for themselves.

Nesbitt offered to allow his former slaves to remain with him through the winter, “but that I couldn’t pay a whole family of negroes to cook a little victuals for me after all that I had lost to both armies.”

While some of Nesbitt’s former slaves may have remained for the winter, many freedmen throughout Maryland began the process of establishing their own communities in towns and rural areas. The seeds for some communities had been sown decades earlier, where free blacks had purchased land and settled. Many freedmen chose to leave their home counties for work in Baltimore and cities elsewhere.

The 1864 constitution freed the slaves of Maryland, but it did not provide for much civil recourse for the treatment many blacks received at the hands of white employers, neighbors, and even county governments. The Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands, more commonly known as the Freedmen’s Bureau, was created by Congress in 1865 to address issues of Reconstruction in the South. The Freedmen’s Bureau also operated in southern Maryland and around the Federal capital city. But by 1866, the Bureau’s activities expanded to cover all of Maryland, a result of numerous complaints of unfair and abusive treatment of black Marylanders.

Initially, the issue of forced apprenticeship of Black children by former masters was a primary focus for the Bureau in Maryland. The post-emancipation Maryland legislature failed to address issue, continuing to allow county orphans’ courts to decide the fate of children, even over their parents’ objections. The apprenticeship grab in Maryland began, according to historian Barbara Jeanne Fields, “the very day of emancipation, all over the state…whisking them off to the county seats, sometimes in wagonloads, to be bound as apprentices by the county orphans’ courts.” In Worcester County alone over 500 children were “bound out” in 1864. Ostensibly, apprenticeship was billed as a form of social welfare, suggesting that only children from families who could not care for them were indentured. Fields noted the action by many former slave owners, however, was a “vague hope” for the recovery of slavery, but in the meantime, apprenticeship served as a source of needed laborers.

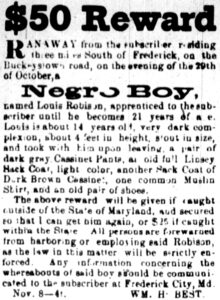

Although mid-Maryland farmers were well acquainted with free Black labor, they too were not immune to the apprenticeship grab. Frederick farmer William H. Best apprenticed 14 year old Louis Robison, apparently against his will. In November 1865, Robison ran away from the Best farm on the Buckeystown Road, prompting Best to offer a $50 reward for his return and warning others not to employ the runaway “as the law in this matter will be strictly enforced.” In a report by William Logan, Register of Wills for Washington County in 1867, there were seven apprentices bound in the county before December 1865. The Orphan’s Court, whose charge it was to sanction such arrangements, “refused to bind persons of color” in the two years following, according to Logan’s report. By 1868, there were 127 contested apprentice cases on record that were handled by the Freedmen’s Bureau in Maryland, involving 206 children largely located in the Eastern Shore counties. All of the cases were settled with the children released from bondage, including Edward Lee’s son, who had been bound “against his consent” by Edward Harris in Frederick County.

The Freedmen’s Bureau played an important role in reuniting family members lost during slavery, separated by the auction block as enslavers sold their “property” at will and irrespective of family ties. Bureau field offices received numerous letters seeking help to find spouses, children, brothers, and sisters. Many were written by the freedpeople themselves, others by those willing to help. In February 1868, Frederick Schley wrote a letter to the Maryland field office on behalf of Ruth Coursey, then living in Frederick City. She was seeking her two sons, Columbus and Charles Coursey, who had been sold south during their enslavement. While she believed Charles might be in Louisiana, she knew that Columbus had been sold by Lewis Ramsburgh to someone in Tennessee. From February through September of 1868, letters were passed from the Bureau office in Baltimore to offices in Nashville, Pulaski, and Knoxville, Tennessee, but to no avail.

In addition to providing legal aid for freedmen involved in court cases, the Freedmen’s Bureau facilitated labor contracts between African Americans seeking paid employment and white farmers and businessmen seeking laborers. Most contracts were for one year of labor at a set monthly or annual pay-rate. Many were arranged for one or two individual laborers or whole families, however larger agricultural operations hired multiple laborers – in some cases hundreds of men – in a single contract. Contracts written out of the Washington, DC field office arranged labor contracts in Maryland, Virginia, and Pennsylvania, as well as New York, Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, and as far as Mississippi. Employers committed to providing “quarters, full substantial and healthy rations, all necessary attendance and supplies in case of sickness,” while employees agreed to work “for the time and rate per month set.” In 1865, thirteen contracts were prepared for twelve Carroll County residents seeking farmhands, house servants, and general laborers. In August 1865, Samuel Bentz, a farmer in Freedom District, hired ten “freed laborers” on a three-month contract to make railroad ties at 7 cents per 8-foot tie produced. Joshua Shipley, another Freedom District farmer, contracted the Cheeks family in September 1865 for a one-year term. Bristo (age 58), agreed to a $70 salary for the year’s work, Sophia (45) $50, and Amelia (14) $40, while Catherin (8), and Meda (4) were promised “quarters and rations.” Five years earlier, Shipley held seven adult men and women, and seven children in bondage. Indeed, of the twelve men who contracted laborers in Carroll County, ten were enslavers in 1860, all of them living in Freedom District. In Frederick County, Jonathan R. Belt of Buckeystown District, who enslaved three African Americans in 1860, hired two laborers, Ned White and David Minters, on an open-ended month-to-month contract.

Perhaps the greatest impact the Freedmen’s Bureau had in western Maryland was its help in the establishment of schools. Although an 1865 Maryland law required that school taxes collected from black landowners “shall be set aside for the purpose of founding schools for colored children,” this provided precious little in the form of monetary support for black education. In Washington County, for example, there were fewer than one hundred black land owners in 1870; the school taxes collected there were actually quite small. In February 1867, Washington County School Board minutes recorded, “…the appropriation made in November last [$30] to Colored Schools shall be equally divided between Williamsport and Hagerstown.” And a year later they paid “to the Colored Schools of the County – the sum of $25 a piece.” Based on this, in 1868, the Board reported to the Freedmen’s Bureau that it had “paid what the law allows for these schools.” According to the Freedmen’s Bureau Harpers Ferry Region director, it was the only county in Maryland to have done so.

Clearly, few county school boards were committed to the education of African-American children and adults. In cooperation with a number of philanthropic organizations working out of Baltimore and the Northern states, the Freedmen’s Bureau assisted in the construction of school buildings and acquisition of teachers for schools in Baltimore City and rural communities throughout the state. In a number of these schools the Bureau only provided the teacher, but did not fund the salary; the African-American communities in fact financed the schools themselves, often operating them in their own church buildings. The Freedmen’s Bureau assisted in the establishment of at least eleven schools in Frederick County, seven in Washington County, and three in Carroll County.

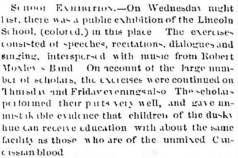

The June 20, 1866, a Hagerstown newspaper, The Herald of Freedom and Torch Light, described “a public exhibition” at the Lincoln School, identified as “colored,” which had been established with the help of the Freedmen’s Bureau five months earlier. “The exercises consisted of speeches, recitations, dialogues and singing, interspersed with music from Robert Moxley’s Band.” The Bureau had provided the school with one teacher, Stillman A. Tucker, “a young gentleman from Massachusetts.” Mr. Stillman oversaw the education of more than one hundred students, according to the article, “and their progress in learning has been very rapid, as one who was present at the examination could not fail to perceive.”

Given the lack of local government funding in the early years of Reconstruction, it was common for church buildings, particularly in rural areas, to double as schoolhouses. This was true despite the involvement of the Freedmen’s Bureau in Maryland. In Sharpsburg, the local black community’s small log chapel, known as Tolson’s Chapel, built in 1866, housed the school with a teacher brought in by the Freedmen’s Bureau in 1868 and 1869. Ezra A. Johnson, the first teacher at the Sharpsburg school, noted in a letter that the Freedmen’s Bureau customarily provided “$20 or $25 for the use of their churches where used as school houses provided the Freedmen would allow the teacher to use it for board, &c…” Johnson, who was having difficulty getting paid, observed in his April 1868 letter, “I have since learned that the Bureau no longer pays for the use of coloured churches…”

In 1869, the Freedmen’s Bureau reported over 2,000 schools established in the southern and border states, with as many 250,000 children and adults attending. It was in 1869, however, that Congress discontinued most of the Freedmen’s Bureau functions, except the education and servicemen’s claims departments. In 1870, education programs ended and 1872, the Freedmen’s Bureau was abolished by Congress.64After the demise of the Bureau’s education program in 1870, county school commissions slowly took on their legal responsibility. County atlas maps drawn in the 1870s show the growing number of “colored” schoolhouses in rural areas. In 1881, Thomas Scharf noted twelve “colored” schools in Washington County. However, Scharf’s list of school buildings in the county revealed only three buildings for black students, and 126 buildings designated for whites. Presumably, church buildings housed the remaining eight colored schools. The school opened in Tolson’s Chapel in 1868 remained in operation in the chapel building through 1898 when the county built Colored School No. 4 in Sharpsburg.

Throughout the last half of the 1860s, black Marylanders struggled to establish themselves as free Americans in an atmosphere of white fear, mistrust, and often-outright bigotry. The quick retreat by many Maryland citizens and politicians to the Conservative Union/Democratic coalition was as much motivated by fear of “negro equality” as by opposition to the Reconstruction policies enacted by the Republican-led Congress. But the national march toward civil rights had begun in 1866 with the passage of the Civil Rights Bill. The first test of the Frederick County courts came in April 1866, when a white man was arrested for shooting a black man. Though the defendant “objected to the admissibility of negro testimony,” Justice Mahoney “ held white man to bail in the sum of $200 or his appearance at the October term of the Circuit Court.” In another case in January 1867, Justice Simmons of Frederick County was arrested for refusing to allow “testimony of colored people” in his court.

Also in 1866, Congress gave African American men in the District of Columbia the right to vote, a move soundly condemned among conservatives in Washington County:

Resolved, That this meeting, asserting that this is a government of white men, framed by and for white men – that we are opposed to negro suffrage here and elsewhere and unqualifiedly condemn the vote of Francis Thomas, Representative in Congress from this district, in conferring upon the negroes the right of suffrage in the District of Columbia and who would in fact, with the friends and the party in power in Congress, fasten this policy on the whole country.

Many opponents of “negro equality,” whose greatest fear was African American suffrage, tapped into the most basic fears of the white population of Maryland, particularly the fear of “miscegenation” or “mixing the blood of the two races.”

The message of fear apparently resounded and in the state election of 1867, voters elected Democrats (Conservatives) across the board. Despite the heavy loss, the editor of the Hagerstown Unionist (Republican) newspaper Herald & Torch Light noted,

Ten years ago the State would have given a larger majority against Emancipation than she now does against colored suffrage. Now all parties are in favor of the former, and we predict that in five years from to-day the latter will have quite as many friends.

Indeed, his prediction was not too far off. In 1870, Congress passed the Fifteenth Amendment, providing the right to vote to African American men in all states, although Maryland did not support the amendment.

Despite setbacks and the prevailing racism of the day, African Americans in mid-Maryland celebrated the freedoms that had been hard won. Over three hundred African Americans, led by a band of black musicians, celebrated by marching through Westminster in 1867. Afterwards participants enjoyed a dinner and listened to speeches. The Westminster American Sentinel described the event: “The Freedmen of this County on Wednesday last had a public demonstration in honor of their emancipation, and we are pleased to say, was one of the most creditable and orderly ones we have ever witnessed. . . . Their conduct throughout was unexceptionable, and might well be emulated by some of our white men who talk so loudly about their superiority.”

African Americans in Frederick County held their first emancipation celebration in August of 1865. A report of the celebration in the Frederick Examiner claimed that 3,000 people attended the event, and that the celebration commenced with the singing of the hymn, “Blow Ye the Trumpet, Blow,” in which the main refrain is “The year of jubilee is come!” In addition to “one of the most eloquent and impressive prayers it was ever our good fortune to listen to,” offered by Rev. Benjamin Tucker Tanner of Frederick’s Quinn Chapel, the main event was an address by Rev. Henry Highland Garnet, one of the most prominent African American leaders in the country at the time.

Two years later even more people attended the Frederick County emancipation celebration. A reporter for the Frederick Examiner said this “was one of the largest gatherings that ever took place in this county.” The gathering was preceded by a grand parade with over 2,500 participants, and between 5-8,000 people crowded into an area known as Worman’s Woods, north of Frederick City, for the actual celebration. The Frederick County emancipation celebration became an annual event, and often special train excursions brought participants from Baltimore, Hagerstown, Westminster, and other cities. These festivals often included parades, speeches, picnics, and other entertainment. This celebration was held every year from 1865 until 1939.

Return to Conservatism

As the rancor of the war years faded, most white Marylanders seemed eager to promote unity between the North and South. A conservative Democratic government regained control of Maryland’s political machinery, former Confederate soldiers regained their citizenship rights, and African Americans were once again denied theirs.

Rev. Benjamin Tucker Tanner, minister of Bethel A.M.E. Church (Quinn Chapel) in Frederick, while looking at the changed status of African Americans in the United States, declared in 1867 that “some of the Kitchen furniture is to be taken into the parlor, and some of the parlor furniture into the kitchen.” This was said following the adoption of the Thirteenth Amendment in 1865 abolishing slavery in the United States; the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1866, which declared that African Americans were indeed citizens of the United States, with at least most of the rights enjoyed by whites (and which was later embodied in the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution, ratified in 1868); and at a time when returning rebel soldiers and other Southern sympathizers in Maryland had been stripped of most of their rights of citizenship. Tanner’s assessment proved too optimistic. African Americans in mid-Maryland persevered in creating a new life after emancipation, but decades of oppression and racism and Jim Crow laws followed the initial years of hope after the war. Unfortunately, it would take a century, and longer, for most of this hope to be fulfilled.

Stories in Focus