As US society during Reconstruction increasingly divided along the “color line,” African Americans found support and opportunities for growth within the structure of their own communities. Rural groupings of African Americans grew around long-established or new Black landowners, often expanding through strong kinship ties. They could be widely scattered or a cluster of farmsteads that formed a community; some were on the edges of rural towns and villages. Similarly, Black neighborhoods in the region’s larger towns and cities expanded around institutions established long before the war. At the center of the Black community framework stood the church, providing not just spiritual and financial support, but also avenues for personal improvement, mutual aid, and freedom to speak openly. Many Black churches served a dual function as places of both worship and education. For the most part, it was the African Americans themselves who took the lead in ensuring that there would be schools for their children and aid for the poor—whether with the help of the Freedmen’s Bureau or state and local governments, or through their own traditions of mutual aid and support rooted in African culture and centuries of slavery and oppression in America.

In his seminal history of the Reconstruction era, Eric Foner described the Black church, schools, and benevolent societies as the “key institutions of Black America” that not only supported African Americans through the daily struggles of the late 19th century, but also “became the springboards for future struggle”:

In stabilizing their families, seizing control of their churches, greatly expanding their schools and benevolent societies, staking a claim to economic independence, and forging a distinctive political culture, Blacks during Reconstruction laid the foundation for the modern Black community, whose roots lay deep in slavery, but whose structure and values reflected the consequences of emancipation.

Henry Louis Gates, Jr. reiterated this idea, particularly around the central importance of the church in African American communities: “In the centuries since its birth in the time of slavery, the Black Church has stood as the foundation of Black religious, political, economic, and social life.”

Geographic Distribution of African Americans in the 1870s

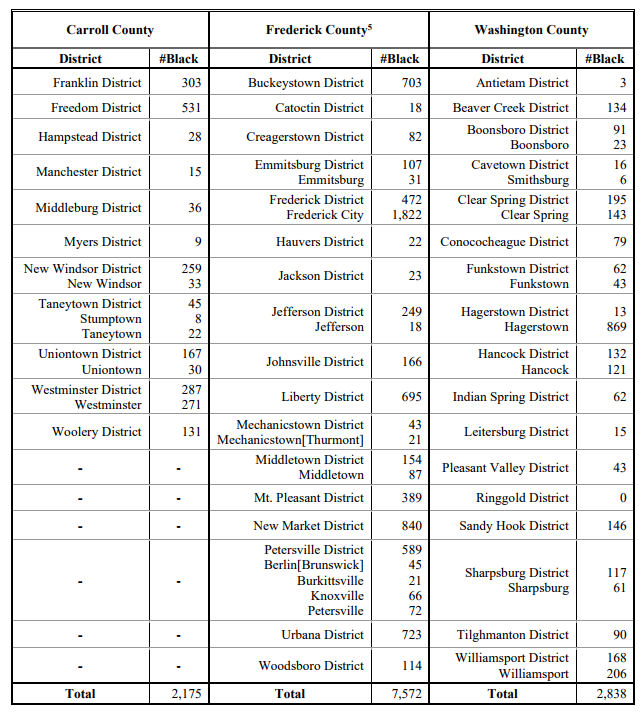

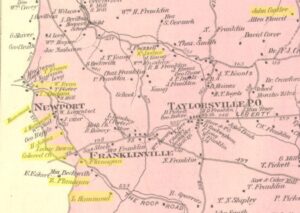

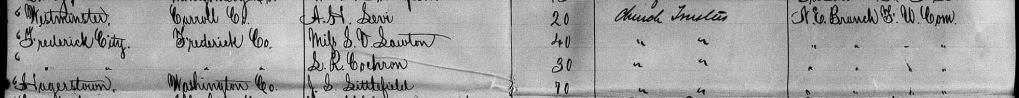

African American population distribution in the mid-Maryland counties of Carroll, Frederick, and Washington before the war influenced the development of Black communities during the post-war Reconstruction years. The county districts in which enslaved and free African Americans were present in larger numbers developed more post-emancipation communities. Those districts with larger pre-war free Black populations also often had more Black landowners, the foundation of rural “cluster” communities and rural town-edge communities. For example, in 1860, Frederick County had a Black population of more than 8,000, of whom 3,200 were enslaved and 5,000 were free. After emancipation, at least 10 rural towns and 14 rural clusters became home to a Black population large enough to build a church and school, in addition to the already well-established community in Frederick City. Most of these communities were in the five southern districts and two eastern districts of the county where most of the county’s enslaved population was located. Washington County had a Black population of 3,100 in 1860, with just over 1,400 enslaved and nearly 1,700 free people. Outside of the Hagerstown community, there were 5 rural town communities and 4 rural clusters. In Carroll County, with a smaller total Black population of 2,000 in 1860, only 3 rural cluster communities formed, in addition to the nascent Union Street community in Westminster. Ten years later, African Americans enumerated in the 1870 census within county districts and for select towns provides clues to the locations of post-war Black communities:

Cluster communities tended to be centralized around one or two Black-owned parcels, with scattered farmsteads and tenancies forming the extended community. In many cases, a core parcel was owned by an individual or family that was free before the Civil War—some claiming ownership of the land for several generations back. In most cases, the initial land purchase was made after emancipation from white landowners, some of them former enslavers, who carved small parcels from their acreage. The land was often marginal, located on thin-soiled hillsides or on wooded land, commonly purchased in parcels of ten acres or less. Typically there was a source of employment nearby, including larger farms, grist or saw mills, tanneries, and iron works, though the predominant employment in the rural communities was farm labor. It was often the Black landowners within rural communities who provided the land for churches and schools, and who played leading roles in their operations.

Kinship played a significant role in the growth of cluster communities. In a study of Black communities in northwestern Montgomery County, Maryland, George McDaniel found: “Not unusually, grandparents allowed their descendants to build houses on their land, thereby converting the homestead into an extended family. Thus, the elderly lived in close proximity to the younger generations in the community and passed on their ideas, values, skills, and ways of life to the young.” In some cases, the land was subdivided and sold to the younger generations or extended families. Adjoining or nearby parcels were purchased by others, often former tenants on nearby farms, as money came available, sometimes decades later.

Like the rural clusters, rural town or village communities tended to cluster around free Black property owners, most often located on the back streets or town edges. These men and women also often provided town lots for churches and schools, frequently serving as trustees, ministers, and teachers. In many cases, these town institutions also served Black families living nearby on scattered farmsteads and tenancies. Many Freedmen’s Bureau schools were placed in centralized rural town locations in order to serve the largest number of students. Black residents in or near rural towns and villages found greater employment opportunities for both men and women, including farm labor and domestic work, but also skilled occupations such as carpenters, barbers, and blacksmiths. Washington County’s rural towns adjoining the C&O Canal—Hancock, Clear Spring, Williamsport, and Sharpsburg—offered canal-related work. Point of Rocks in Frederick County offered work on the B&O Railroad, while in Carroll County, the Western Maryland Railroad employed Black workers along its route across the county.

Westminster, Frederick, and Hagerstown, the seats of government in the three counties, already had well-established Black neighborhoods. These neighborhood communities were largely separate from the cities’ larger white populations. Urban areas afforded better employment opportunities for African Americans, from the more common domestic service, day labor, and skilled labor positions, to industrial labor and, for some, as proprietors of small businesses. The established Black neighborhood communities in Frederick and Hagerstown, which already included church buildings before the war, were well-positioned for the influx of Black residents over the decades following emancipation.

Frederick County Communities

Kinship played a significant role in the growth of cluster communities. In a study of Black communities in northwestern Montgomery County, Maryland, George McDaniel found: “Not unusually, grandparents allowed their descendants to build houses on their land, thereby converting the homestead into an extended family. Thus, the elderly lived in close proximity to the younger generations in the community and passed on their ideas, values, skills, and ways of life to the young.” In some cases, the land was subdivided and sold to the younger generations or extended families. Adjoining or nearby parcels were purchased by others, often former tenants on nearby farms, as money came available, sometimes decades later.

Like the rural clusters, rural town or village communities tended to cluster around free Black property owners, most often located on the back streets or town edges. These men and women also often provided town lots for churches and schools, frequently serving as trustees, ministers, and teachers. In many cases, these town institutions also served Black families living nearby on scattered farmsteads and tenancies. Many Freedmen’s Bureau schools were placed in centralized rural town locations in order to serve the largest number of students. Black residents in or near rural towns and villages found greater employment opportunities for both men and women, including farm labor and domestic work, but also skilled occupations such as carpenters, barbers, and blacksmiths. Washington County’s rural towns adjoining the C&O Canal—Hancock, Clear Spring, Williamsport, and Sharpsburg—offered canal-related work. Point of Rocks in Frederick County offered work on the B&O Railroad, while in Carroll County, the Western Maryland Railroad employed Black workers along its route across the county.

Westminster, Frederick, and Hagerstown, the seats of government in the three counties, already had well-established Black neighborhoods. These neighborhood communities were largely separate from the cities’ larger white populations. Urban areas afforded better employment opportunities for African Americans, from the more common domestic service, day labor, and skilled labor positions, to industrial labor and, for some, as proprietors of small businesses. The established Black neighborhood communities in Frederick and Hagerstown, which already included church buildings before the war, were well-positioned for the influx of Black residents over the decades following emancipation.

Fredericktown was already developing as the region’s market center when it was designated the seat of government for the newly-formed Frederick County in 1748. By 1820, the city boasted a population of over 3,600 people, including 702 African Americans, both enslaved (437) and free McDaniel, “Black Historical Resources in Upper Western Montgomery County,” . See “Slavery and Freedom in 1860” section in “The Coming Storm” essay, wwwdevelop.crossroadsofwar.org. (265). By that time, two Black churches – Quinn or Bethel African Methodist Episcopal (AME) and the “Old Hill” or Asbury Methodist Episcopal (ME) – were serving Black residents who lived in small household clusters on the south and east edges of town. Fifty years later, and five years after the close of the Civil War, the 1870 census enumerated over 1,800 Black men, women, and children in the city of Frederick.

The 1870 US Population Census for Frederick City, showed that African Americans lived in all of the seven “wards” or tax divisions within the city. While many individuals lived as servants or laborers within white households, a total of 336 family units lived in independent or shared households and 17 of those were property owners. Frederick’s Black community continued to grow and concentrate on the east and south sides of the city, as it had before the war. Wards 1 (316 total Black population) and 2 (466 total), included East Street, Middle Alley, and the east ends of Church through Seventh Street. On the south side of Frederick, Wards 5 (241 total), 6 (290 total), and 7 (362 total), encompassed All Saints, South, and West Patrick Streets, as well as Brewer’s Alley and Cat Alley. In the wealthy central-city Wards 3 & 4, African Americans appeared in much smaller numbers, 83 and 64 respectively, and were predominantly living in white households.

While many of Frederick’s Black residents worked in domestic service and day labor in 1870, there were at least five blacksmiths and five tinners, eight barbers, four carters (transporter of goods), three ice dealers, one carpenter, one stone mason, two shoemakers, and five people working in hotel service. John Murdock and William J. Brown owned their own ice dealerships; Charles Roles owned his retail grocery; and Warner Cook, Benjamin Tanner, Henry Williams, and Jacob Nicholson were listed as clergymen.

By 1868, the Black community of post-war Frederick was served by three churches. Quinn Chapel AME Church, on East Third Street, served not only as a place of worship and community gathering place, but also housed the first school for Black children in the city, beginning in March 1865. The two-story brick church building was constructed in 1855. Two other churches served congregations on the south end of Frederick. The Asbury ME Church was still located on East All Saints Street. On West All Saints Street, “The Baptist Church of Frederick,” formerly a white church, was occupied by a Black congregation by the 1860s.

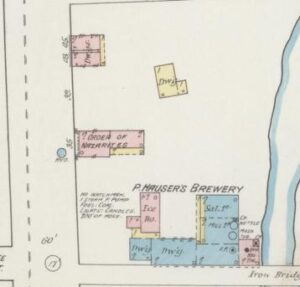

The school located in the basement of the Quinn Chapel was one of two Freedmen’s Bureau-sponsored schools for African Americans in Frederick City. In April 1865, a second school was opened in the Asbury Church and by 1867, had two teachers and 47 students enrolled. In 1869, the Baltimore Association provided the teachers for both schools and paid $10 per month rent to each church for the use of their building. There is evidence the Baptist Church may have also hosted a school. Groups that promoted mutual aid and fellowship within the community began to appear as early as 1865, when the Grand United Order of Odd Fellows in America (GUOOF), or Black Odd Fellows, authorized the formation of the Evening Star Lodge in Frederick City. A second lodge followed in 1866 called the Mt. Zion Lodge. The groups likely met initially in private homes or churches. In 1871, the 26th annual general meeting, called the Annual Moveable Committee, convened at the meeting place of the Evening Star Lodge in Frederick with delegates representing 88 lodges from across the US. It was reportedly the largest such meeting held in the history of the Black Odd Fellows at that time. It appears the fraternal group known as the Grand United Order of Nazarites had the earliest lodge building, located on West All Saints Street near Brewers Alley on the 1887 Sanborn Insurance Map of Frederick. The brick building was later occupied (in 1921) by the Knights of Pythias. The Odd Fellows and other such groups gathered for the purpose of fellowship, but also to promote mutual aid among its members.

They establish internal funds to help sick or disabled members, and to defray the cost of funerals for members and their families. Other groups, including the Beneficial Society of Laboring Sons of Frederick, established burial grounds where African Americans could be interred. The Laboring Sons Cemetery was opened in 1851 along the west side of Chapel Alley between Fifth and Sixth Streets on the east side of town. In 1880, The Working Men’s Association established the Greenmount Cemetery on West Seventh Street, the second all-Black cemetery in Frederick. While a Black-only burial lot adjoined the “Old Hill” Asbury Church on East All Saints Street, the Quinn AME and Baptist churches did not have cemetery lots.

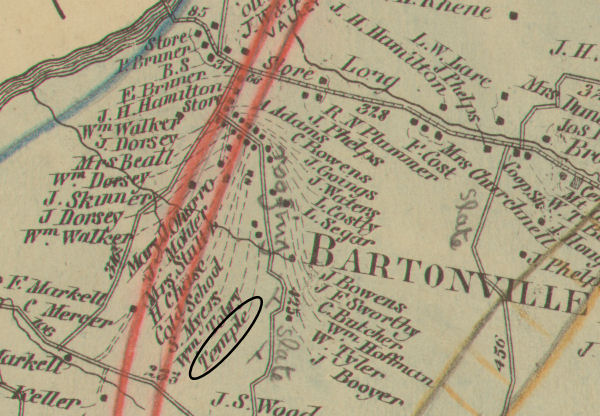

Outside of Frederick City, rural Black communities or household clusters were located in all sections of the county. The communities that had begun to form before the war, including the Black town-edge neighborhoods in Emmitsburg (1830), Lewistown (1840s), Libertytown (1830s), Middletown (1820s), Mt. Pleasant (ca.1856), and New Market (1830s), and the rural clusters of Mt. Ephraim (1814), Mountain (1813), Poplar Ridge (1820s), Pattersonville (1853), Bartonsville (1838), Old Fields (1855), and Mount Olive continued to grow after 1865. In addition to these, many newly freed African Americans and their families formed new communities around post-war land acquisitions by men and women who were able to save some of their wages toward the purchase of a home. Like the communities formed before the war, these were located on the edges of small towns and villages, in agricultural household clusters, and on the mountainsides along the county’s western boundary.

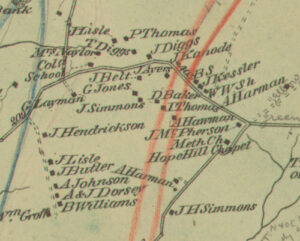

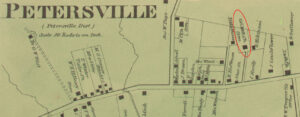

As the 1870 Population Census table (above) shows, the greatest concentrations of African American residents were in districts in the south and east sections of the county where the largest numbers of enslaved people lived before 1865 – Petersville Dist. (793), Urbana Dist (723), Buckeystown Dist. (703), and Jefferson Dist. (267) in the south and New Market Dist. (840), Liberty Dist. (695), and Mt. Pleasant Dist. (389) in the east. It was in these districts that many of the post-war rural communities formed and grew. New town-edge Black neighborhoods appeared in the south-county towns of Buckeystown, Jefferson, Petersville, and Point of Rocks. The largely agricultural southern districts saw the formation of many rural cluster communities: a small grouping of roadside dwellings formed the community known as Centerville about halfway between Ijamsville and Urbana, (Fingerboard Road and Ijamsville Road); the Pleasant View community was located south of the village of Doubs; the Hope Hill community (Flinthill Road and Park Mills Road) formed on a hilltop west of Urbana near the Monocacy River; Halltown was north of Point of Rocks); Brookville was on South Mountain Road north of Knoxville; Della and Greenfield were near Licksville; and the widely scattered households along Burkittsville Road (Coatsville, Route 17), Gapland Road, and Mountain Church Road were located west and north of Burkittsville. In the eastern districts, new communities included Fountain Mills near Monrovia and a cluster outside of New London, while the remote enclave known as Old Fields (near Unionville) and Mount Olive, on the Carroll County line opposite Union Bridge, continued to grow.

Churches were typically the first institution to mark a community grouping, many with associated burial grounds. In rural towns and villages, the church often stood at or near the center of the Black neighborhood. Those churches also served African American households from the surrounding area, whether living on isolated farmsteads or in small clusters. Brookville and

Coatsville community residents attended the Mt. Zion AME Church in Knoxville or the Union Bethel AME Church in Petersville. Other churches were established in rural areas where a cluster of scattered Black households formed a community. The Ceres Bethel AME Church (Gapland Road, 1858/rebuilt 1872) served residents along Mountain Church and Gapland Road as well as the growing but widely scattered Coatsville community along Burkittsville Road (Route 17). In 1869, the residents of the Hope Hill community cluster near Buckeystown, purchased the “Hope Hill Church” from its white trustees. Sunnyside ME Church (built 1885), served the community along Mountville Road as well as residents in the tiny community called Halltown. The Mt. Ephraim community (1814) added Bell’s Chapel in 1874 to serve its growing population. The Mount Olive Church (1850) served the surrounding community, likely including residents of Old Fields, both in Frederick and Carroll County. In 1871, a group of men from the Old Fields purchased land as trustees “for the purpose of Erecting a House thereon to be used for a school house and to Worship in.” In 1883, a dedicated church building called Keys Chapel at Old Fields was constructed. In many cases, like Keys Chapel (1883), the Sunnyside ME Church (1885), and the Ebenezer ME Church in Centerville (1883), church buildings were constructed years after a congregation was formed.

Between 1865 and 1870, many of these community churches hosted a Freedmen’s Bureau school. A school was established in Middletown in 1865; in Libertytown, Burkittsville (area), Mt. Pleasant, and Petersville in 1866; New Market, Point of Rocks, and Hope Hill in 1867; and in Lewistown in 1870.

A schoolhouse was apparently in place by 1867 in Centerville, but in September 1868, Ebenezer Church minister Rev. Alexander Kennedy requested the Freedmen’s Bureau’s help to rebuild their schoolhouse “that was burnt last Spring by some ruffians.” Freedmen’s Bureau funds to build a schoolhouse in Emmitsburg were reportedly approved in 1867, however a dispute between the Black residents and the white builder delayed completion until the fall of 1869. (See Freedmen’s Bureau Schools Database for images of Teacher’s Monthly School Reports)

Federal funding for the Freedmen’s Bureau education department was ended by Congress in 1870 and the responsibility fell to the Maryland counties by law in 1872. In the 1870 state election, the first in which Maryland’s Black voters participated, their support for Radical Republicans in the legislature helped to change state laws that shifted the outlook for Black education in Maryland. In 1872, a new law was passed requiring every county to have at least one Black school, for which some state funding would be provided.

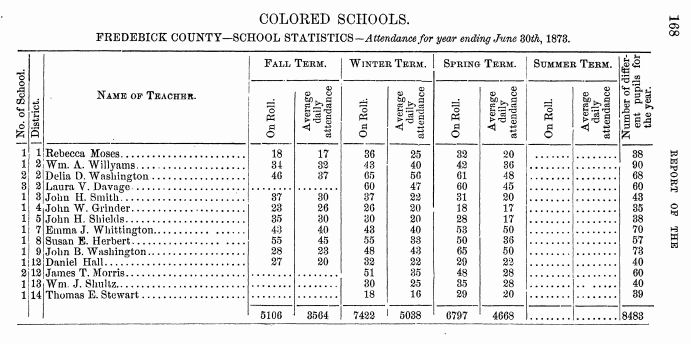

The Frederick County School Commissioners had already begun providing minimal funds to a few of the established “Colored schools,” including Emmitsburg’s Lincoln School, in 1869. After the 1872 law was passed in Maryland, the Commissioners laid out a plan for eighteen “Colored schools” across the county, though only fourteen were in operation during the 1872-73 school year, according to the state’s Annual Report.

The early county schools remained in the buildings, often still churches, that were used by the Freedmen’s Bureau-sponsored schools. Later purpose-built schoolhouses were constructed by the county. A few remain standing today (2024), including the 1888 schoolhouse “Mountville Colored School” (MIHP #F-2-44); the “Hopeland School” (MIHP #F-7-37), built ca. 1910, replaced an earlier building; the “Doubs School,” built by the county School Commission in 1902 (Pleasant View MIHP #F-1 -139, survey district); Buckeystown old school building still stands near the church, now occupied as a residence; and the school at Old Fields that was later converted to a private home. The Comstock School (MIHP #F-7-25), built for the Mt. Ephraim community in 1898, was not constructed by the county but by the wealthy owner of the nearby Stronghold Manor.

Like the Black community living in Frederick City, the ruralcommunities in the county also formed lodges associated with several well known societies. In 1869, the Needham Lodge of the Grand United Order of Odd Fellows (GUOOF) was formed in Burlin [sic] (Brunswick). Two new lodges were established in 1871, the Mt. Phillip Lodge in Middletown and the Star of the West Lodge in Burkittsville. In Bartonsville, members of the Order of the Galilean Fishermen, a mutual aid society originally organized in Baltimore in 1856, were granted dispensation to form a tabernacle or lodge, probably before 1873 when it apparently shows on the Titus Atlas map as “Temple.” In 1917, the lodge trustees purchased another parcel (on today’s Tobery Road) in Bartonsville on which they built a new meeting hall.

Washington County Communities

Elizabethtown, later renamed Hagerstown, was named the county seat of Washington County in 1776 when the new county was carved from Frederick County. The town, platted in 1762, had already been in existence as a busy market and mill town for more than ten years. In 1820, the US Population Census for Hagerstown listed 2,300 white people, 112 free African Americans, and 119 enslaved. Over the forty years that followed, Hagerstown’s white population grew slowly reaching just a little over 3,600; and while the enslaved Black population fell to 60 individuals, the free Black population had swelled to 449 men, women, and children.

The African American neighborhood community that had its beginnings in the first decades of the 19th century continued to grow around the Asbury ME Church, established on Jonathan Street in 1818, and the Ebenezer (Bethel) AME Church on Bethel Street (1820) where a cemetery was in place as early as 1843. By 1870, nearly a third (869) of Washington County’s Black population (2,838) lived in Hagerstown, largely within the North Jonathan Street neighborhood between West North Street (Avenue) and Weller’s Alley to the south. While many were born in Maryland, a number of Hagerstown’s Black residents hailed from Virginia, Pennsylvania, and North Carolina, and a few from Tennessee, Ohio, and Washington, DC.

As with other larger towns, Hagerstown offered a variety of employments beyond the most common domestic service and general laborer, according to the 1870 census. Hotel workers included cook, waiter, porter, and hostler. Skilled occupations included barber – there were eleven barbers of whom six were from the Wagner family – dressmaker, seamstress, tanner, plasterer, two blacksmiths (John Fields and George Cook), carpenter, butcher, nurse, drayman, and a “clergyman” (Benjamin Brown). One individual worked as a store clerk while another gave his job as “works in furnace.” Aaron Booth operated a “Notion store.” Eight of the barbers were among the 60 African American property owners, along with other skilled occupations such as stone mason, butcher, and “Methodist preacher” Edward Hammond. However, the majority of property owners were employed as unskilled laborers, farmhands, domestic servants, and hotel workers, while a few were women who stayed home as house keepers. At least seven of the property owners were USCT veterans, including Samuel Broome, Benjamin Brooks, and Mark Marshall, as well as Thomas Henry and Robert, Perry, and Joseph Moxley, who were all members of the local “Moxley Band” recruited into the 1st Brigade Band in 1863.

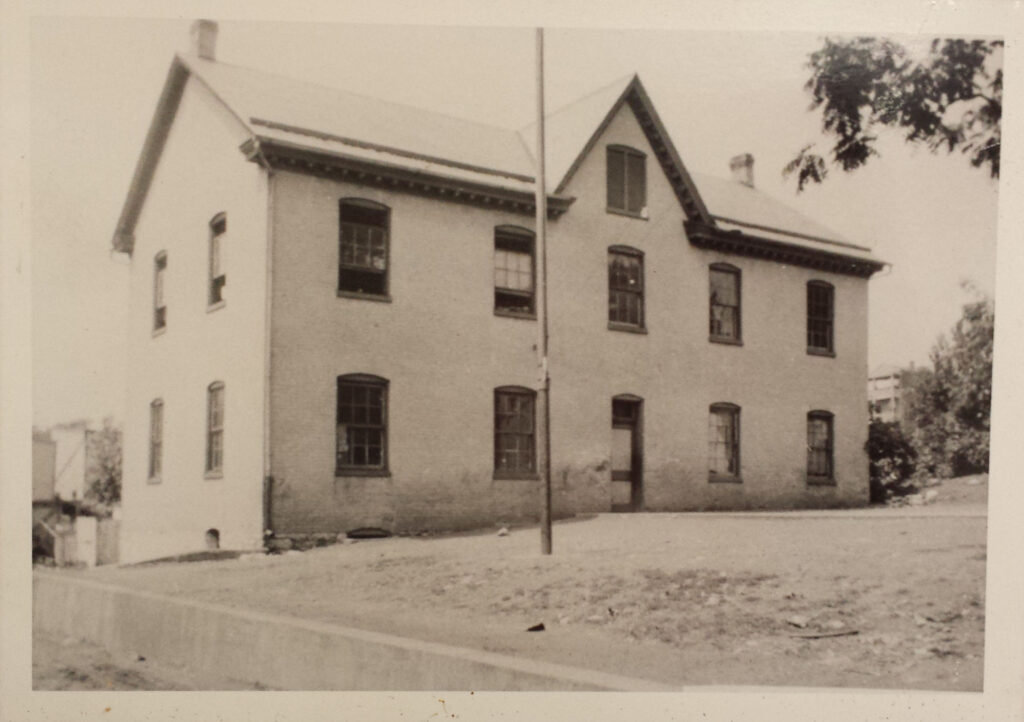

Freedmen’s Bureau records indicate a school was established in Hagerstown in the fall of 1866 with as many as 66 students enrolled and one white teacher supplied by the New England B.F.A.C. The Lincoln School, as it was called, was held in the Ebenezer AME Church basement for two years and by January 1868, there were 133 students enrolled and two teachers, one white and one Black. In 1869, the trustees of the Hagerstown school requested $100 from the Freedmen’s Bureau to “aid in the erection of their house,” saying they had received only $300 from the county’s Board of School Commissioners, the amount they were “entitled to…from the County School Fund under the law.” The Bureau supplied 40,000 bricks valued at $100 toward the construction of a two-story brick schoolhouse. In 1870, the census listed 51 African American children in Hagerstown as having “attended school within the last year,” while the majority of adult African Americans in Hagerstown could not read or write. The Lincoln School remained in operation under county supervision, beginning in 1871 following the demise of the Freedmen’s Bureau education division.

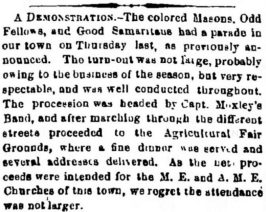

Hagerstown’s Black community included a Masonic lodge (Prince Hall Freemasons) as early as 1868, when the local newspaper reported on a “Colored Masonic Procession” led by Chief Marshal; Samuel Nimmy and accompanied by the Moxley Band. By 1873, the Masons were joined in a fundraising parade by two other Black societies, the Odd Fellows (GUOOF) and members of the Independent Order of Good Samaritans and Daughters of Samaria (Good Samaritans). The Rock Springs Lodge No. 1603 of the GUOOF or Black Odd Fellows, was officially sanctioned on November 1, 1873. It was followed by the formation of a Household of Ruth, the women’s Odd Fellows group, in 1879. In 1883, they constructed the American Hall on West Bethel Street for their meetings. The American Hall also served as a community meeting space used by other groups, including the Masons and the Lyon Post No. 31, Grand Army of the Republic (GAR), formed in 1883 by USCT veterans from Hagerstown and the surrounding area. Although the Good Samaritans participated in a local parade as early as 1873, the Perseverance Lodge No. 3 was officially incorporated in 1875, their stated purpose to be “beneficial, benevolent and charitable, to nurse the sick and to bury the dead and to assist the needy.” That same year, the Hagerstown lodge hosted the semi-annual national meeting. In 1884, the Perseverance Lodge purchased a lot on the east side of North Jonathan Street on which they constructed a meeting hall, which first appears on the 1892 Sanborn Insurance Map of Hagerstown. In 1897, the Perseverance Lodge established the Halfway Colored Cemetery on seven acres just south of Hagerstown after the Bethel AME Cemetery was closed in 1893.

Outside of the city of Hagerstown in 1870, nearly 2,000 African Americans lived in the smaller towns and rural districts across the whole of Washington County. The largest town communities, according to the census, were located in Clear Spring (143), Hancock (121), and Williamsport (206), with smaller groups in Sharpsburg (61), Funkstown (43), and Boonsboro (23). Black households in the rural districts were similarly concentrated: Clear Spring District (195), Hancock District (132), Williamsport District (168), and Sharpsburg District (117), with significant numbers also in the Sandy Hook District (146) and Beaver Creek District (134). It was largely in these areas where community institutions would appear after 1865 in Washington County.

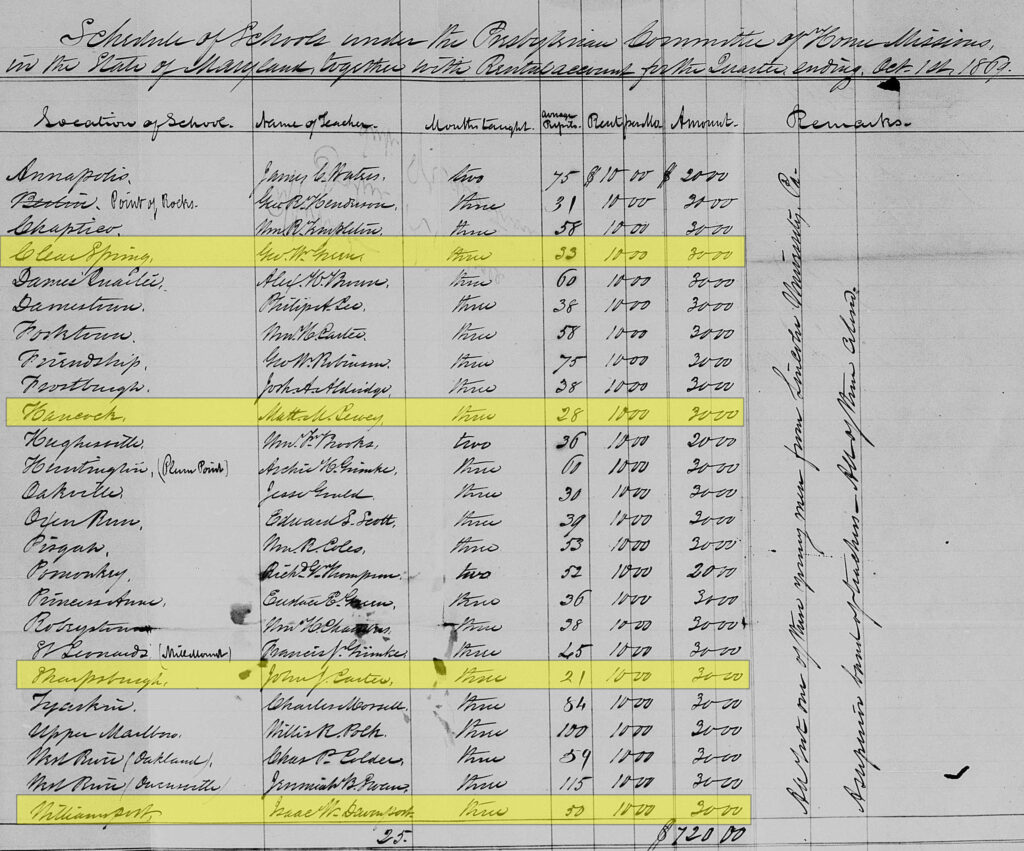

According to the 1870 census for Washington County, only 202 African American children had attended school “within the last year,” with one quarter of those being in Hagerstown. Between 1866 and 1870, the Freedmen’s Bureau aided in the establishment of schools in or near the smaller towns of Williamsport (1866), Clear Spring (April 1868), Sharpsburg (April 1868), Sandy Hook (fall 1868), and Hancock (1869). The Williamsport community, largely located along South Artizan Street, was apparently worshiping in a small frame building as early as 1866, where the Freedmen’s Bureau school was located in the basement. In 1868, the trustees of the Asbury Methodist Episcopal (ME) Church purchased the adjoining lot and built a larger brick church, donating the old church building to be used as a school. The Clear Spring Black community, located on Martin and Mill Streets, represented 21 percent of the total Clear Spring population. The ME church was constructed on a lot on Mill Street, purchased in 1866, where the Freedmen’s Bureau school commenced in its basement in 1868. The small town of Hancock also had a relatively large Black community. Beginning in 1868, the school was held initially in the unfinished ME church building. In Sharpsburg, the sanctuary of the small log ME church (later called Tolson’s Chapel) served as the classroom during the week. All four of these schools were provided teachers through the Presbyterian Commission on Home Missions, which also paid ten dollars monthly rent to the churches for their use as schools. The Sandy Hook school was located north of the village in Pleasant Valley (see discussion below). Though there was a growing community in the area, there was not yet a Black church and the Bureau paid $75 to help the community construct a school building.

Scattered clusters of Black households developed in the rural areas outside of the smaller towns and villages. Typically, the rural clusters grew around one or more Black landowners, the households often connected by kinship and many living as tenants on Black-owned land. Rural African American communities have been identified in the south-county Sandy Hook District (Pleasant Valley/Yarrowsburg), the east-county Chewsville District (Jugtown/Crystal Falls), and the western district of Indian Spring (Big Pool area/Fort Frederick). Of the seven Black households in the Indian Spring District, three were landowners with real estate valued at $800, $3,000, and $6,000, the latter being Nathan Williams who owned 345 acres including the ruin of the old stone Fort Frederick. In 1873, a county “colored school” was noted in the district, with 16 “different pupils” and an average daily attendance of eleven students. In 1899, a new school was built on land sold by Williams’ heirs.

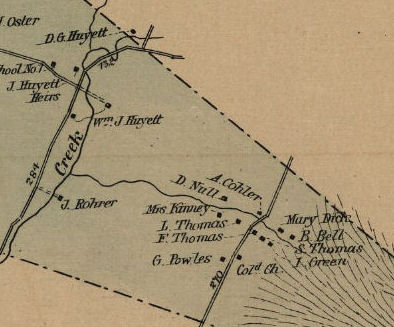

The east-county Black community known as Crystal Falls (later Jugtown) was located on the west face of South Mountain overlooking the Huyett family farms and lime manufacturing complex. William Huyett subdivided 16 acres for sale in smaller lots in the 1870s, on which the community developed. The Crystal Falls AME Church and cemetery were located on part of the Huyett land sometime before 1878. No school was provided by the county in the Chewsville District and it seems likely the Black children of Crystal Falls attended the school in Beaver Creek District, just a few miles to the south.

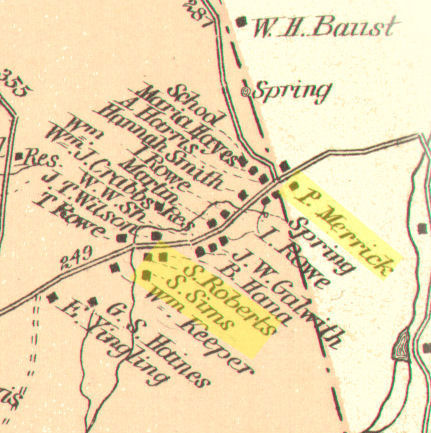

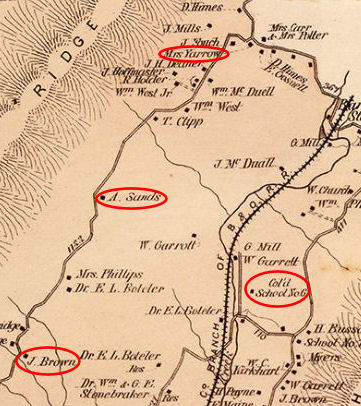

In Washington County’s southern-most Sandy Hook District (Pleasant Valley), a scattered community of Black households grew along the east face of Elk Ridge, often called Yarrowsburg after longtime Black resident Polly Yarrow. The Freedmen’s Bureau school referred to as “Sandy Hook” or “Pleasant Valley” was in operation by 1869, with as many as 36 students under teacher Hamilton E. Keys, a recent graduate of Storer Normal School in nearby Shepherdstown, West Virginia.

The Freedmen’s Bureau school was likely in this area, where by 1872, county “Col’d School No. 6” was in operation.

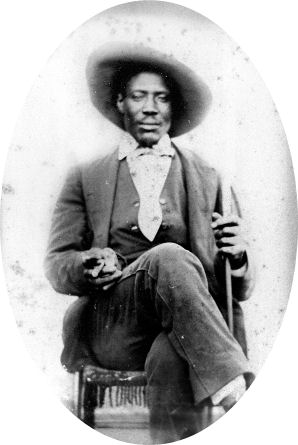

Perhaps the oldest of these rural communities in Washington County was located on and near Red Hill, historically part of the Antietam Iron Works. Free African Americans had been living in the Red Hill area since as early as 1800, and by 1860 there were 20 independent Black households with five landowners. Aaron Booth, owned seven acres on which he hosted several tenants and began to sell the rented lots to his tenants in 1863. In September 1863, Booth enlisted as a sergeant in the USCT, one of seven men who enlisted from the Red Hill area. In 1870, the census listed 23 households in the Red Hill community. The census-taker described the Red Hill community for the local newspaper: “Along the mountain we found quite a number of colored families. They all seemed to be industrious, well-to-do and intelligent. At Red Hill, they have erected a neat little church, where, we believe they have school in the winter months, and preaching at regular stated periods.”

The Pleasant Hill AME Church was located near the summit of Red Hill, with a cemetery adjoining the building. Although no record has been found of a Freedmen’s Bureau-sponsored school at the church, it appears the local community had organized a school by 1870. The school continued in the church building under county administration, noted on the 1877 Atlas map as “Colored School No. 5.”

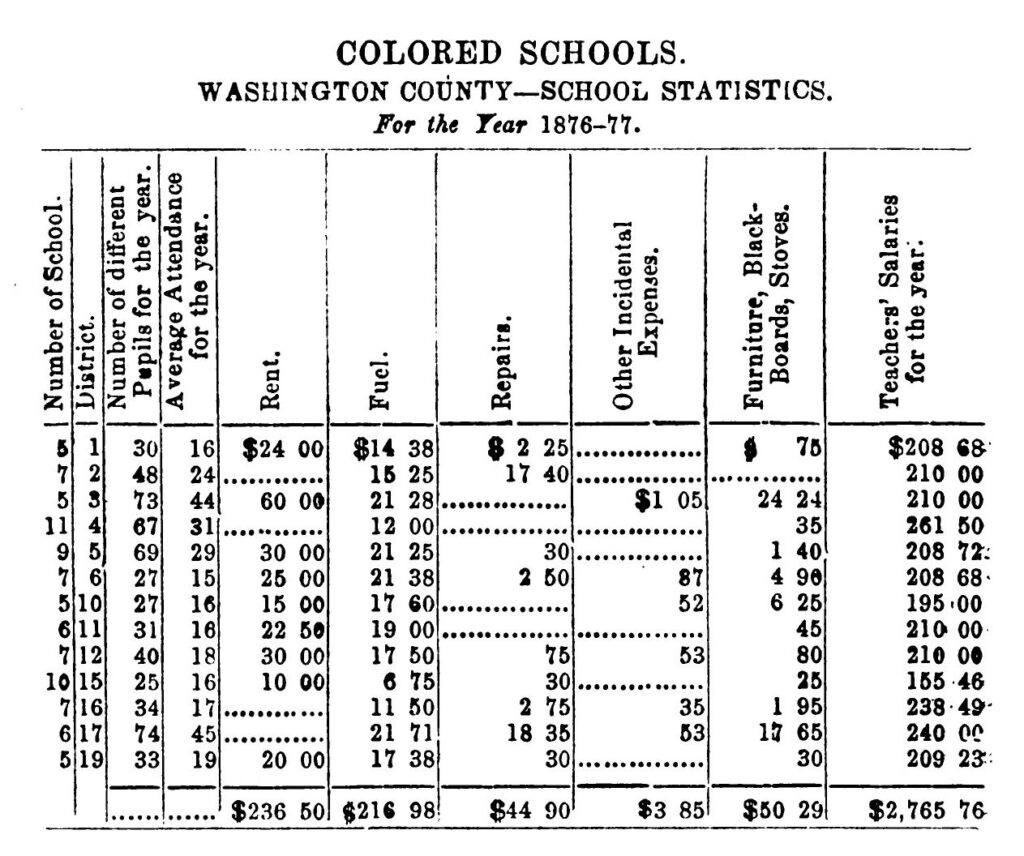

During the 1872-1873 school year, county-run schools for African American students were present in only nine of the eighteen districts. In 1876, there were thirteen schools in operation, but only four appeared to be in county owned buildings. The remaining nine schools likely continued to be held in Black churches, for which the county paid rent, like Tolson’s Chapel (District 1, No. 5), where the school remained through the 1898 purpose-built schoolhouses were constructed by the county in the 1890s, thirty years after the county took on the responsibility for educating its Black children.

Like the Black residents of Hagerstown, those residing in the rural towns and districts also participated in groups dedicated to mutual aid, burial, and even politics. In 1870, there were 18 African American men over the age of 21 in the Red Hill area who were eligible to vote after the passage of the Fifteenth Amendment to the US Constitution. Sometime prior to the November presidential election of 1888, the men of Red Hill formed the “Colored Republican Club.” On November 2, 1888, two days before the election, the club held a “mass meeting” to hear speakers on the subjects pertaining to the politics of the time. In 1892, the club took on the name “Star of the West.” The Black Odd Fellows (GUOOF) formed lodges in Sharpsburg and Williamsport. The Sharpsburg D.R. Hall lodge was established in 1869. It is likely they met in Tolson’s Chapel until they built their own lodge hall on a town lot purchased in 1901. The Williamsport lodge, named Rescue, was formed in 1880; it is unknown if the hall was ever constructed.

![Eveline [Brown], domestic servant at D. Gaither Huyett’s farm called The Willows in Chewsville District, Washington County, ca.1890. (courtesy Virginia Clagett et al)](https://crossroadsofwar.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/22.Eveline.ca_.1890.jpg)

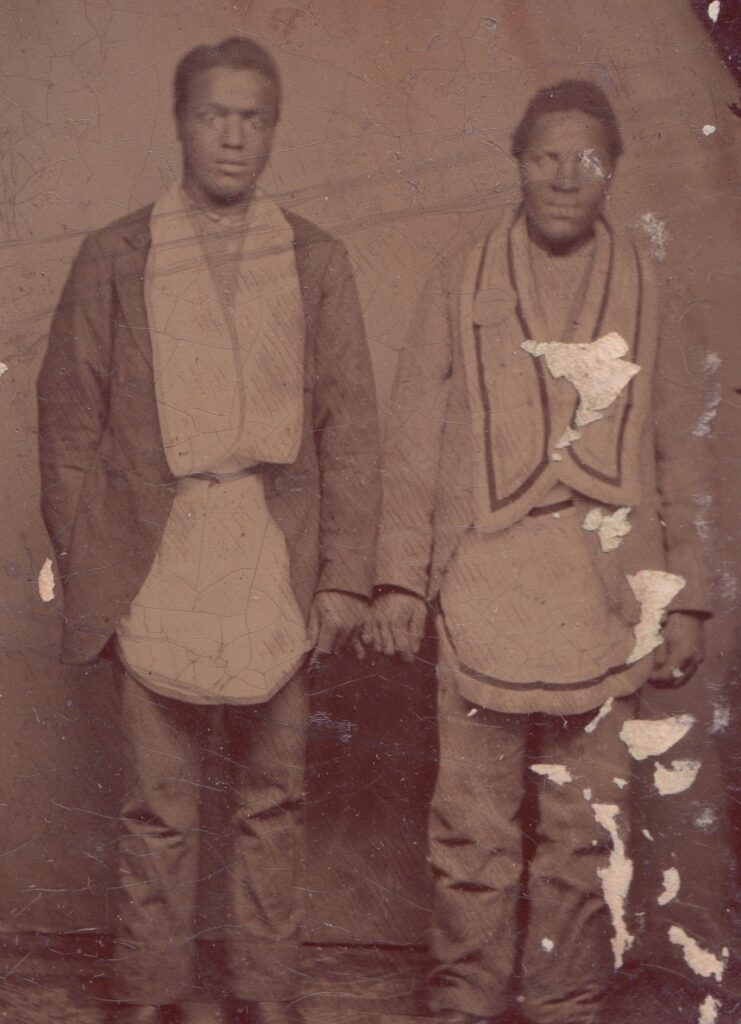

Washington County was a largely rural, agricultural county through the 19th century. Significantly, the Chesapeake & Ohio (C&O) Canal ran the length of the county’s southern border, following the Potomac River. While farm labor or general labor was the most common occupation listed for African American men in 1870, there were a significant number of men (11) employed as “Boatman” on the C&O Canal in Hancock, Clear Spring, and Weverton (near Sandy Hook). One, William Cooper, was a “Lock Tender” in Clear Spring. In 1878, four Black men were employed as boat captains on canal boats: J.W. Johnson on the boat “John Sammon,” Lewis Robinson on “Viola H. Weir,” Wilson Middleton (of Sharpsburg) on “Dr. F.M. Davis,” and Kirk Fields on “John W. Carder.” 63 Married women often stayed home “keeping house” and caring for children. Men, women, and older children were often employed as domestic servants working – and sometimes living – in white households. Some were skilled laborers, including Thomas Wilson and his son Charles, both blacksmiths, and his other son John, a barber, all living in the Crystal Falls community.

Carroll County Communities

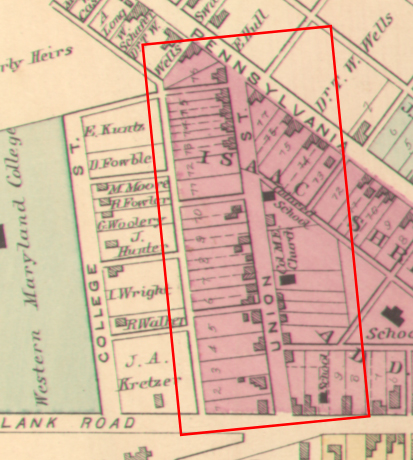

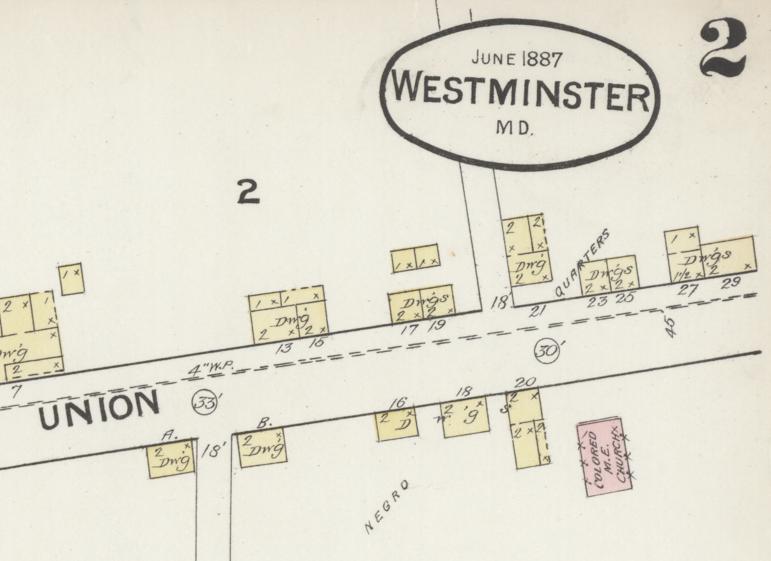

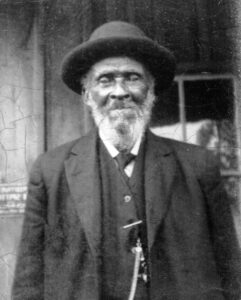

Carroll County was carved from eastern Frederick County and western Baltimore County in 1837, at which time the small town of Westminster was designated the county seat. Located at the center of the agricultural county, by 1870 Westminster was a busy market and railroad town with a total population of over 2,300 residents, 271 of whom were African American. The Union Street neighborhood of Black households had begun to develop in the 1850s. While many of the improved lots were tenancies, William and Elizabeth Harden were the first Black lot owners in 1864. At that time, no church or school was located in the Union Street neighborhood. John B. Snowden, a farmer who owned land outside of the city, had been holding “protracted meetings” of his Methodist congregation in his home for many years.

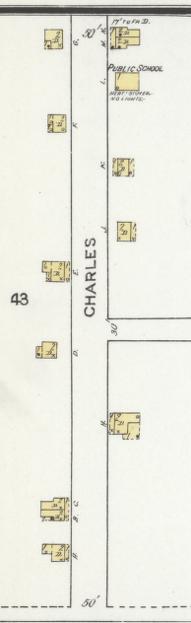

It was after Maryland emancipation in 1864 that the Black community on Union Street in Westminster really began to grow. In March 1865, John M. Snowden, son of minister John B. Snowden, purchased a quarter-acre lot on Union Street where he likely had previously been living as a tenant. Nine months later, Amos Bell purchased the adjoining lot, described as being between John Snowden and Elizabeth Harden. Amos and Rebecca Bell subdivided their lot in August 1867. Keeping the half on which they lived, they sold the remainder to the trustees of the Union Street Methodist Episcopal Church, including Amos Bell, John M. Snowden, William Lowery, George W. Bell, Lewis Charlton, William Parker, and Nicholas Parker. It seems a church was quickly erected and by November 1867, was also used to house a Freedmen’s Bureau school in Westminster, with 34 students attending. The arrangement was temporary however. Two years later, in October 1869, John M. Snowden and his wife Mary Ann sold part of their lot to the trustees of the Union Street School House. In April 1870, Thomas Snowden, son of John B. Snowden, was the teacher in the Freedmen’s Bureau-sponsored school he called “Westminster School,” with 46 students enrolled. The 1887 Sanborn Fire Insurance Company map indicated “negro tenements” on Main Street near Union, in addition to the “negro quarters” on Union Street.

A second African American neighborhood developed on Charles Street on the southern edge of Westminster, just outside the city boundary. Among the early residents of this community were Elias Cole and his brother John W. Cole, both USCT veterans wounded in action at Dutch Gap, Virginia. The 1870 census for Westminster shows a cluster of at least 12 Black households around those of John and Elias Cole. Seven of the households were property owners, while others were tenants, including John Cole’s family and Martha Spriggs who appear to be tenants on the property owned by George Dickinson. At least seven children from the Charles Street neighborhood were attending school in 1870, likely at the Union Street Freedmen’s Bureau school. By 1872, the county school commission opened a second school for Black students in Westminster, which would have been located on Charles Street.

Of the 45 Black households listed in the 1870 census for Westminster, there was a total of 24 home owners, including John B. Snowden and William Beho in the Union Street neighborhood, who each held real estate valued at over $1,000. Snowden’s occupation was “ME Minister” while Beho was a farm hand. The most common employment was domestic service and the majority of those appear to have lived in the white households where they worked. Other employments included laborer, wagon maker, cooper, washer woman, hostler, and nurse (probably childcare). James Parker was the town barber; several individuals worked at the Western Maryland College as cook and waiter. Four men were occupied as miners at the “ore bank,” including William Adams, Francis Penn, Simon Gooden, and James Harden; and Thomas B. Snowden was listed as “School Teacher.”

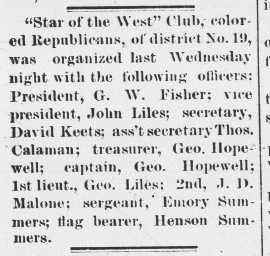

Two mutual aid societies were organized the African American community of Westminster. In 1867, the GUOOF authorized the formation of the St. Thomas Lodge, sponsored by the Olive Lodge in Baltimore.Sometime before 1879, residents organized a chapter of the Good Samaritans and Daughters of Samaria. According to a newspaper report in April of 1879, 50-60 members of the organization paraded through town “in the regalia of the Order, in line, preceded by the Sam’s Creek Band, also colored.” That evening, continued the report, “a festival was held in Union Street hall for the benefit of the lodge.” The Westminster community also had its own group of musicians, described in 1882 by The Democratic Advocate as the “colored drum corps, with bass drum, four kettle drums and two fifes.”

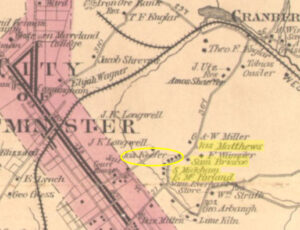

The 1870 census table (see above) indicates that many African Americans (287) lived outside of the Westminster town boundaries in the greater Westminster District. One enclave was located northeast just outside the town boundary and appears to have grown around the farm owned by John B. Snowden. By 1870, there were 14 Black households, including four landowners, which appear on the 1877 map in a line along the road to Cranberry Station. Another small enclave lived outside of the town boundaries along the old New Windsor Pike running southwest from Union Street. Given their proximity to town, it is likely that both of these small household groupings affiliated with the Union Street community institutions.

In the rural area southwest of Westminster, near Warfieldsburg, a scatter of at least 12 Black households formed a community around the Western Chapel ME Church. Five of the households were landowners, including David Brown, a farmer (and minister) whose land was valued at $1,000. The land on which the Western Chapel stood was purchased by church trustees Amos Johns, George W. Cain, David Black, Cato Sides, and Joshua Brown in 1868 from nearby white landowner Abraham Cassell. At just over one acre of land, the parcel was large enough to support a cemetery as well. Rev. David N. Brown, a USCT veteran, served the congregation as its minister and is among those buried in the cemetery. John N. Squirrell, who served with Co. G, 28th Regiment, USCT, is also buried there. In December 1869, Western Chapel became the site of a Freedmen’s Bureau-sponsored school with 33 students.

Other Carroll County districts that had larger African American populations in 1870 included Franklin (303), Freedom (531), New Windsor (259, plus 33 in town), Uniontown (167, plus 30 in town), Woolery (131), and Taneytown (45) Districts. The 1870 census indicates small communities of Black town residents in Uniontown, New Windsor, Taneytown, and the village known as Stumptown. The small Black community in Uniontown began to form through the 1850s on the east edge of town where three African Americans owned the lots on which their homes were located. By 1870, the Hayes and Jones families still lived in town, joined by William and Suzie Smith, W.H. Brown and family, and Lewis Smith, with 12 individuals spread among the five households. The remaining 21 Black residents of Uniontown lived and worked in white households. The Mount Joy ME Church, established in 1858 by Singleton Hughes, was located just outside the west boundary of Uniontown. Only three independent Black households were located in the town of New Windsor in 1870, two apparently on the southern edge of town along High Street, while Joshua Owens may have been on the east edge of town.

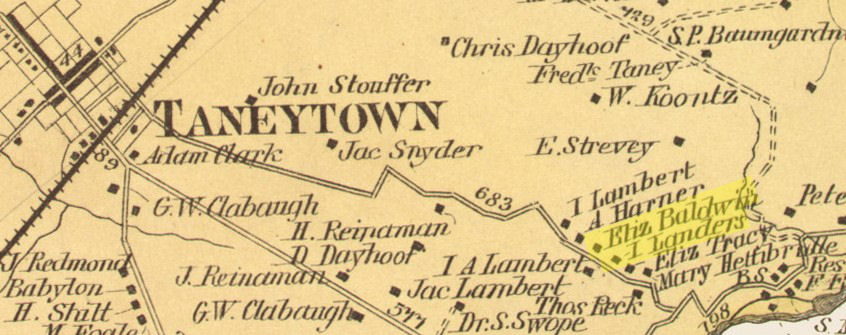

Of the 30 Black residents in Uniontown, 16 lived and worked in white households. The Black residents of Taneytown numbered 22 in 1870, all but four of whom lived in the three Black households in town. John W. Cook and Caleb Johnson, both veterans of the US Colored Cavalry, owned their homes, as did Lucy Watson. All three were members of the St. Joseph’s Catholic Church of Taneytown and are buried in the church cemetery. The tiny village of Stumptown, southeast of Taneytown, included the homes of Elizabeth Baldwin and Isaac Sanders. The eight family members in these two households, represented 20 percent of the total village population.

Both Uniontown District and New Windsor District included substantial Black populations outside of the towns at the center of each district. In the Uniontown District, a cluster of free African American households formed west of Uniontown near the district border. The area, about halfway between Uniontown and Union Bridge and extending into the Union Bridge District, became known as Middletown or Muttontown. In 1867, Lloyd Coates, John Thompson, Josiah Key, William H. Walker, Joseph Hughes, Dennis Green, John Henry Thompson, Joseph Parker, Stephen A. Brooks, and Isaac Landzell purchased a lot as trustees to build a school using lumber supplied by the Freedmen’s Bureau. The school, located on today’s Bark Hill Road, opened by January 1868, identified in the Freedmen’s Bureau record at that time as the “Middletown (Carroll)” school, and continued as late as July 1869. The building reportedly also served as the meeting place for an African Union Methodist Protestant congregation.

In the New Windsor District, there were three clusters of rural Black households. The smallest was a scatter of households in the Mt. Vernon area, including C.M. Pike [Caleb Pike] and H. Dukins [Henry Dugan] who appear on the 1877 Atlas map in that area. Another cluster of 13 Black households formed around the Wakefield Station area, with five Black landowners, including Daniel Woodyard (map), Harriet Bell, Wesley King (map), Perry King (a “Bone Merchant”), and David Brown, a farmer whose land was valued at $1,000. The 1877 Atlas map also shows a “Col Cem” in this area, but there is no record of a Black church. The McKinstry’s Mill/Priestland area community, located on the western border of the New Windsor District, included as many as 22 Black households. The community extended into the Union Bridge District, adding as many as nine additional Black households. The 1877 Atlas map for the Union Bridge District shows a “Cold School” near the home of Benjamin Washington and a blacksmith shop (“B.S.”) likely operated by Benjamin Jones. Both Washington and Jones were listed in New Windsor District in 1870 and in Union Bridge District in 1880. Jones served as one of the founding trustees of the “Priestland Colored School” in 1874, along with Calvin Dunson and Thomas Harp. The community, also very close to the Frederick County line, was reportedly associated with the Mount Olive ME Church established in Frederick County in 1850.

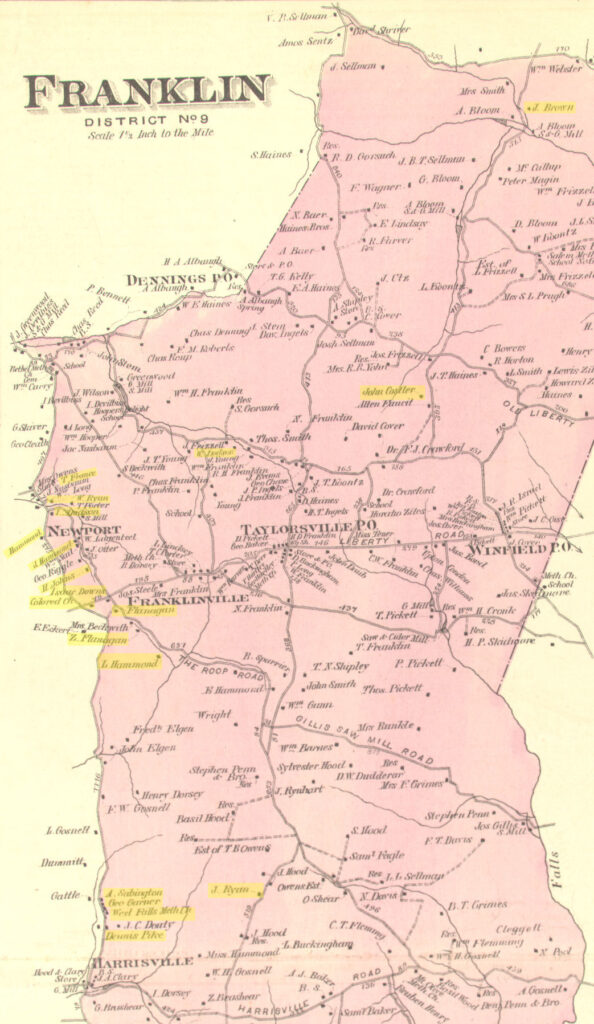

In Franklin District, the pre-war community associated with the Fairview Church, known post- 1865 as Newport, included as many as 19 Black households in 1870 – with several more added by the time the 1877 Atlas map was drawn and many others living across the county border in Frederick County. According to the 1870 census, 14 of the Black households in the Newport area (Franklin District) were landowners. The combined household of farmers John T. and Moses Hammond owned land valued at over $1,800; Zacharias Flanagan’s farm was valued a $2,100. Nearly all of the residents in this area worked as day laborers or farm laborers, except Abraham Bell and Jeremiah Butler who were occupied as blacksmiths. A second cluster of largely tenant Black households grew in the apparently sparsely populated agricultural area to the south around Harrisville (north of Mount Airy). Known as Dorseytown, by 1870 there were possibly as many as 17 Black households in the area, but only three were landowners. In 1883, John Anderson, James W. Johnson, William Holland, Vachel Dorsey, and John T. Bell, trustees of the “Colored Methodist Episcopal Church,” purchased an acre of land on the east side of “Harrisonville Road” [sic] for the purpose of erecting a church. It appears that neither the Newport or Dorseytown communities hosted a Freedmen’s Bureau school between 1865 and 1870.

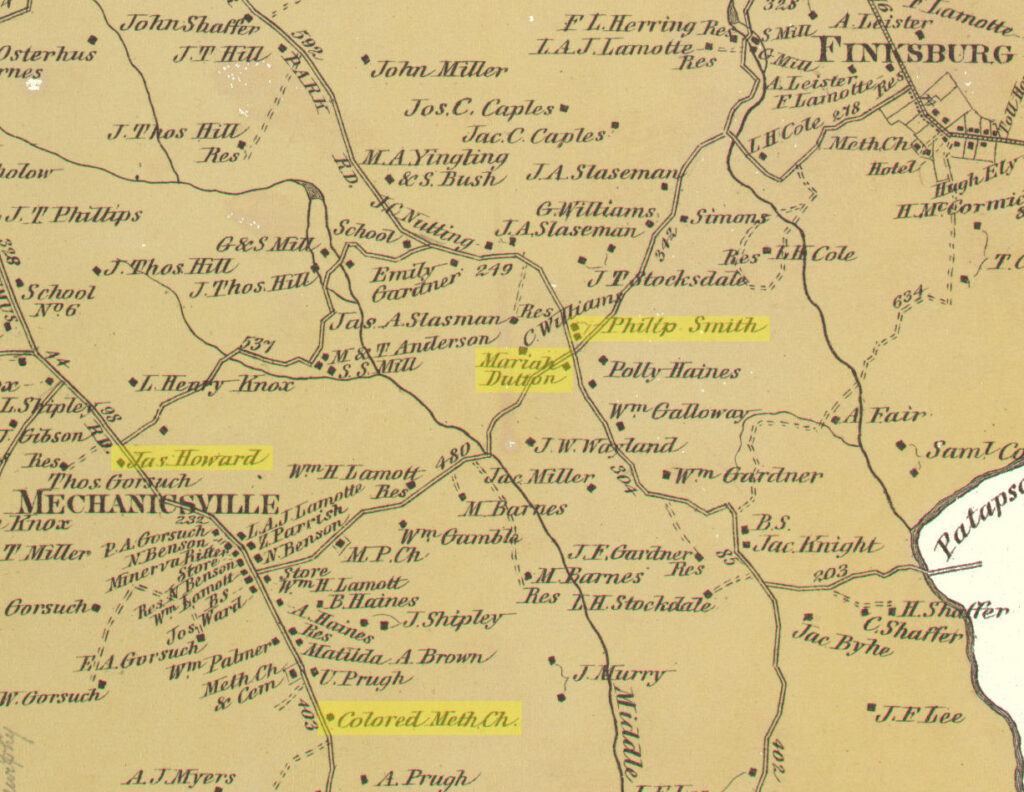

Woolery District and Freedom District, were both located in the southeastern section of Carroll County adjoining Baltimore County. The Woolery District hosted one of only three Freedmen’s Bureau schools known in Carroll County. The Carrollton School was likely located outside of the small (white) Carrollton community. The 1870 census for Woolery District indicates a relatively scattered African American population with no definitive cluster in the Carrollton area. Most of the Black households appear to be in the south half of the district, in the area between Mechanicsville (1877 map; Pleasantville in 1862; today’s Gamber) and Finksburg. Just south of Mechanicsville the 1877 map shows the location of a “Colored Meth Ch.” This church appears in the same location as a church indicated on the 1862 Martenet map of Carroll County. In 1869, Henry Pool sold a lot of just under two acres, “with the church and all the improvements,” to the trustees of the “Methodist Episcopal Colored Church,” later known as Pool’s Church, including Lewis R. Barnes, James Howard, Jacob Hardy, Philip Smith, and Elias Morris. Both Howard and Smith were landowners in the areaand their names are indicated on the 1877 map.According to the 1860 census “Slave Schedule,” Freedom District residents held the largestnumber of enslaved African Americans (381), nearly two-thirds more enslaved people than in Franklin District (135). After slavery was abolished in Maryland in 1864, Freedom District remained the home of more than 500 African Americans in 1870, living in a total of 77 independent households. Most were tenants, with only 15 landowners recorded on the 1870 census.

At the time the census was taken, the largest cluster of Black households, and Black landowners, appears to have been located in the agricultural area southwest of Eldersburg, centered on an area known as White Rock. The 1877 Atlas map for Freedom District shows a “Col Ch” in the White Rock area. Nearby was the farm of Samuel Rhubottom (Ruebottom), valued at $3,300, Philemon Dorsey (near Isaac Dorsey on the map) with a farm valued at $3,750, and George Squirrel and Thomas Berry, both with land valued at $1,000 on the 1870 census. Many more were tenants scattered across the rural south half of the district. In 1868, trustees Joseph Fawcett, Philemon Dorsey, and Allen Nugent, purchased two and a half acres to establish an ME Church and cemetery, today known as the White Rock Independent Methodist Episcopal Church.

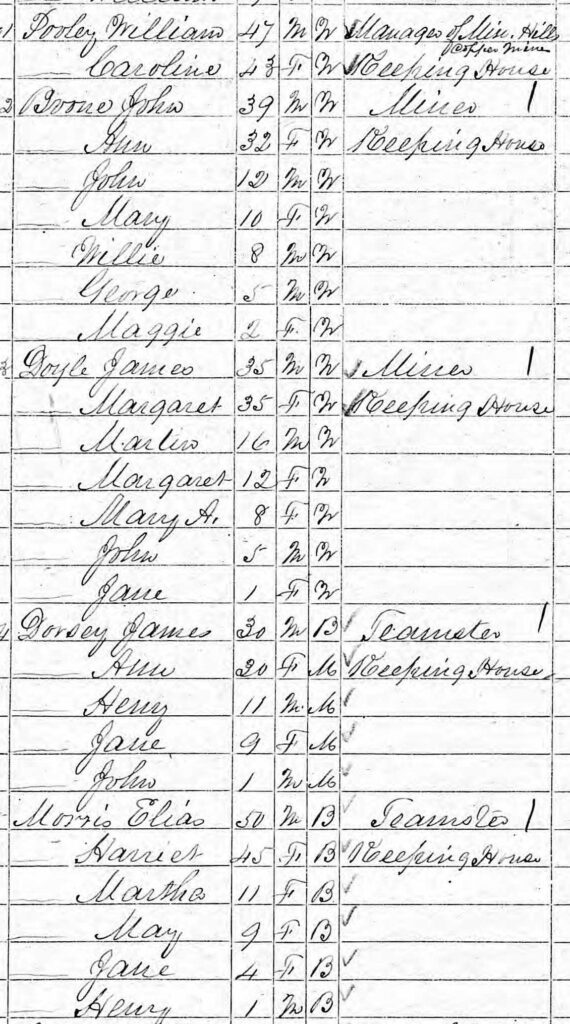

A second smaller cluster of Black households was indicated on the 1870 census around the Mineral Hills Copper Mine in the northern section of Freedom District. There, James Dorsey and Elias Morris were occupied as teamsters and George Barney as a miner. Occupants of nine other households in the area worked as day laborers and farm workers. In the rural crossroads area of Pleasant Gap, George Dicus owned land and worked as a blacksmith, and Beall Mason was a “plasterer” and landowner. While there is no record of a Freedmen’s Bureau school held in Freedom District, in the fall of 1873, the county school commission opened a school in the district (District 5) with 40 students enrolled. The school was located in the White Rock Church, for which the county paid rent, and continued to be the only school in the district until 1886. According to county school records from 1887, the second school was called the Brindletown School, with John H. Henderson as the teacher. It is unknown where this school was located within the district however.

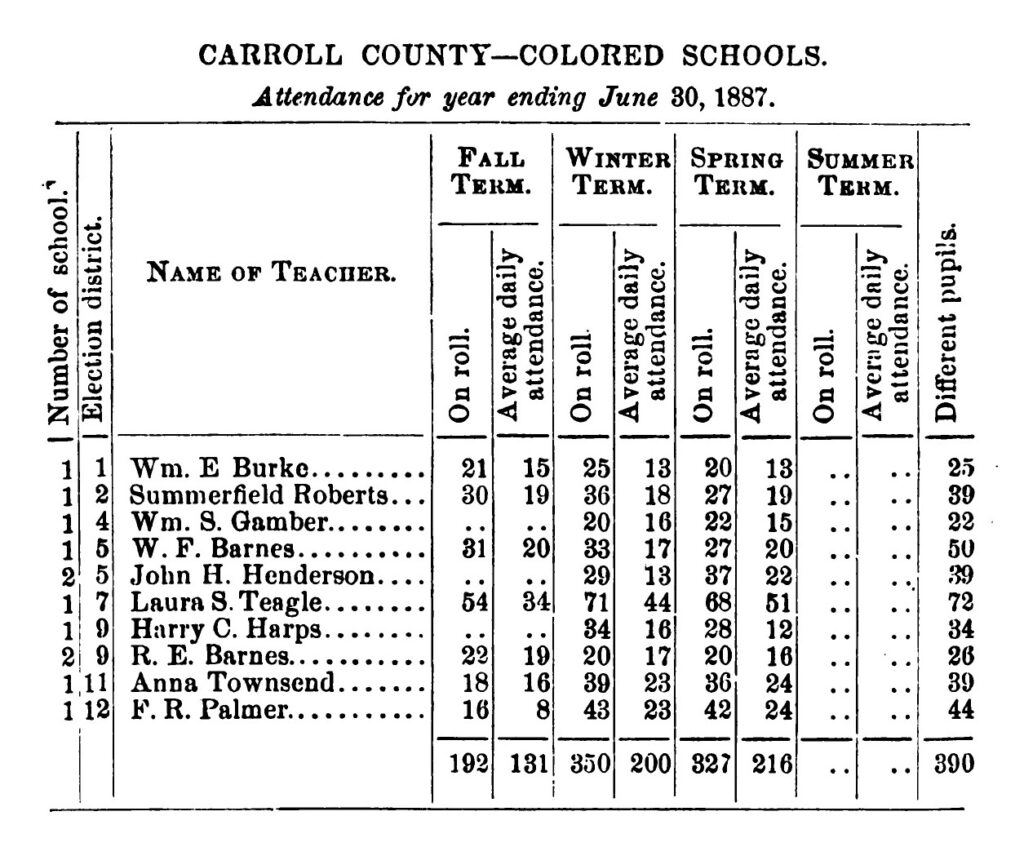

Freedmen’s Bureau records appear to indicate only four schools were established in Carroll County between 1868 and 1870, when the Bureau’s education division was dismantled by Congress. Maryland State Board of Education annual reports show that in the 1871-72 school year, the Carroll County School Commission operated only two “Colored Schools,” in District 2 (Uniontown) and District 7 (Westminster). The following year there were five schools, seven by the end of 1874, and in 1887, there were ten schools. In 1877, the county school commission reported that they did not own any of the “colored” school houses and that there was “no rent paid for ‘colored’ schools.”

As in the other counties in the region, African American community organizations in Carroll

County formed in the larger towns, including the Thaddeus Stevens GAR Post in New Windsor.

Simon Murdock’s obituary (1933) noted that he “was commander of Thaddeus Stevens Post No.

40, G.A.R., and a charter member of Good Samaritan Lodge No. 39…instituted in 1866.” According to The Democratic Advocate, a Westminster newspaper, in the fall of 1879, multiple

Good Samaritan Lodges from Carroll County “enjoyed an excursion to Baltimore on Thanksgiving Day.”91 In 1871, the Flower of the Day Lodge No. 1462, GUOOF, was formed in

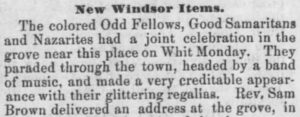

“Mount Olive, Maryland.” Benjamin Dunson, Benjamin Harp, and Benjamin Washington, were reportedly trustees of the lodge. Both Dunson and Harp were veterans of the USCT.92 In May 1885, the town of New Windsor reported a gathering of “Odd Fellows, Good Samaritans and Nazarites at the grove.”

Conclusion

The end of the American Civil War brought freedom to enslaved African Americans and the prospect of each individual’s right to the pursuit of happiness. But the period of Reconstruction in the US and the decades that followed were fraught with the deep-seated and ongoing divide over African American civil rights. Even after Black men were given the right to vote in elections by the Fifteenth Amendment to the US Constitution, their civil power was limited by local racial prejudice, intimidation, and violence. In the most extreme, the violence committed against African Americans known as lynching – summary murders under the guise of justice – was perpetrated by white mobs who rarely faced consequences for their outrages. Lynchings occurred at least four times in the mid-Maryland counties. In Frederick County, three Black men were murdered by white mobs: James Carroll in 1879, John Biggus in 1887, and James Bownes in 1895. In Carroll County, Townsend Cook was arrested near Mt. Airy in May 1885 for the alleged rape of a white woman. Cook was reportedly taken from the Westminster jail by a mob of “50 horsemen” and hanged “to make an example of him.”

In the face of this and other oppressive measures taken by white Americans to prevent the social and civil integration of Black Americans after 1865, many turned inward to find support and encouragement. African American communities, whether closely located households in city or town neighborhoods or clusters of households scattered across the rural landscape, were deeply connected by the institutions of church, school, and mutual aid organizations. In the post-war American society that had “granted” enslaved people freedom, but denied African Americans many basic civil rights, these institutions provided safe spaces to worship, be educated, to speak freely, and to provide mutual support.