From the first commemorative activities of the wartime generation to the present day, the legacy of the Civil War continues to reflect the enduring power of both “history,” an intellectual endeavor that prizes critical thinking and seeks objective truth, and “memory,” which rests on emotion rather than reason and is often subjective, sanitizing, and selective. As later generations viewed the war through these two very different sets of lenses, the efforts to remember those who participated often stirred controversy along with commemoration.

From the first commemorative activities of the wartime generation to the present day, the legacy of the Civil War continues to reflect the enduring power of both “history,” an intellectual endeavor that prizes critical thinking and seeks objective truth, and “memory,” which rests on emotion rather than reason and is often subjective, sanitizing, and selective. As later generations viewed the war through these two very different sets of lenses, the efforts to remember those who participated often stirred controversy along with commemoration.

Remembering the Dead

The ebb and flow of battle across the Maryland region created a serious problem for those communities left to deal with war’s most lethal legacy, that of burying the dead. For many, this became a sacred duty, and for years after the end of the conflict, soldiers’ final resting places evolved into something more: shrines of remembrance.

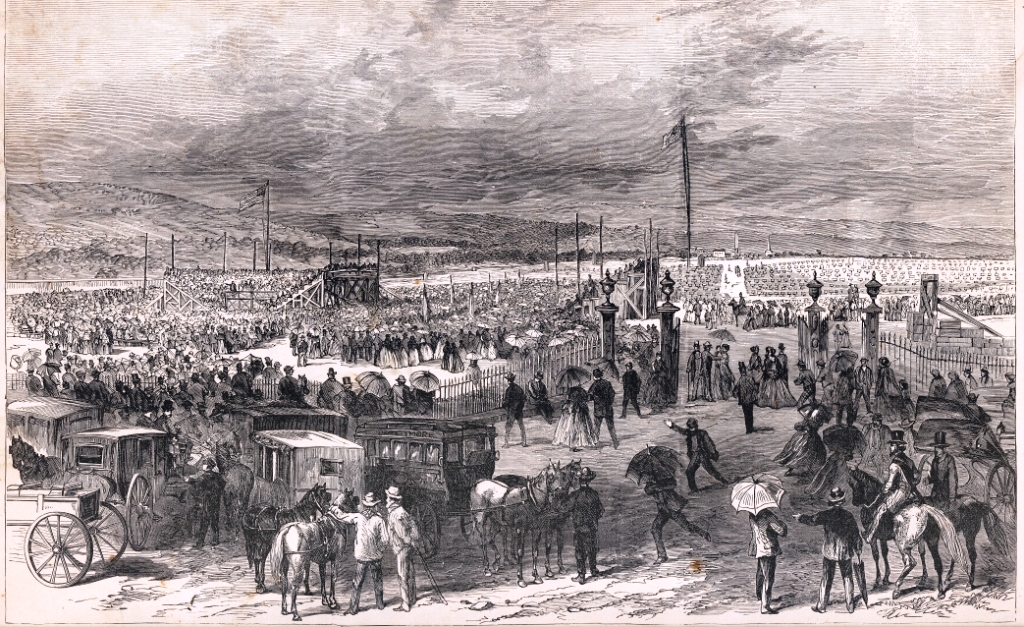

At Antietam, Ball’s Bluff, and Gettysburg, national cemeteries preserve the memory of the Union dead. Gettysburg established its burial ground first – a site on Cemetery Hill (part of the battlefield already crowned by the town’s Evergreen Cemetery), and Pennsylvania Governor Andrew Curtin solicited support from the other Northern states. Although designated the Soldiers’ National Cemetery, state governors demanded recognition of their individual states’ sacrifices; thus, architect William Saunders divided the concentric semicircles of graves into state plots, plus two for unknown soldiers and one for U.S. Regulars. Samuel Weaver was employed to superintend the exhumation and identification of the bodies of Union soldiers. The remains were removed and re-interred in the new cemetery at a contracted rate of $1.59 per body. On November 19, 1863, at the invitation of local attorney David Wills, President Abraham Lincoln presented a few “appropriate remarks,” his immortal Gettysburg Address, to dedicate the cemetery.

The Soldiers’ National Cemetery quickly became a site that inspired reflection and remembrance, and the first monuments to be erected on that great battlefield in the late 1860s still stand within its walls. On May 1, 1872 it formally became part of the National Cemetery system, and as recently as 1997 a set of remains recovered from the battlefield was buried there with full military honors. Today, uniformed reenactors come by the thousands for the annual Remembrance Day parade and solemn ceremony on the Saturday closest to the November 19 dedication anniversary.

The Soldiers’ National Cemetery quickly became a site that inspired reflection and remembrance, and the first monuments to be erected on that great battlefield in the late 1860s still stand within its walls. On May 1, 1872 it formally became part of the National Cemetery system, and as recently as 1997 a set of remains recovered from the battlefield was buried there with full military honors. Today, uniformed reenactors come by the thousands for the annual Remembrance Day parade and solemn ceremony on the Saturday closest to the November 19 dedication anniversary.

Although the battle of Antietam occurred nine months before Gettysburg, plans for its cemetery started more slowly. In 1865, Maryland’s legislature approved funds for a cemetery for both Union and Confederate dead, but when eighteen other Northern states also contributed funds, plans were revised and the ground was reserved for Union dead only. At the formal dedication on September 17, 1867 (the battle’s fifth anniversary), the cemetery held at least 4,697 sets of Union remains gathered from nearby battlefields and hospitals. Federal legislation passed in 1870 authorized the Secretary of War to take charge of the cemeteries at both Antietam and Gettysburg, although the former cemetery was not turned over to the War Department until 1877. Today, the forty-four foot tall soldier statue dedicated in 1880 and nicknamed “Old Simon,” stands at the center of the state plots. As at Gettysburg, Antietam’s first regimental monuments were dedicated within the cemetery.

While the skirmish at Ball’s Bluff resulted in far fewer losses, a small stone enclosure there contains the remains of fifty-four Union soldiers, only one identified. A single Confederate marker outside the wall honors fallen color-bearer Clinton Hatcher of the 8th Virginia. The burial ground languished in comparative isolation for years, and its formal accession by the federal government did not occur until 1904. The local community felt a proprietary attachment to the site, however, and twentieth century efforts to disinter the Ball’s Bluff dead for reburial in the much larger Culpeper National Cemetery – which administers Ball’s Bluff National Cemetery – failed when residents of nearby Leesburg and local members of Congress opposed such action.

While the skirmish at Ball’s Bluff resulted in far fewer losses, a small stone enclosure there contains the remains of fifty-four Union soldiers, only one identified. A single Confederate marker outside the wall honors fallen color-bearer Clinton Hatcher of the 8th Virginia. The burial ground languished in comparative isolation for years, and its formal accession by the federal government did not occur until 1904. The local community felt a proprietary attachment to the site, however, and twentieth century efforts to disinter the Ball’s Bluff dead for reburial in the much larger Culpeper National Cemetery – which administers Ball’s Bluff National Cemetery – failed when residents of nearby Leesburg and local members of Congress opposed such action.

Local cemeteries throughout the region were used to bury Union soldiers who died in battle or from disease an accidents. In most cases, bodies were later reinterred in national cemeteries. Frederick’s Mount Olivet Cemetery, for example, once contained the remains of over 1,000 Union dead before most were removed to Antietam National Cemetery.

African American soldiers who served the Union seldom won equality in death in national cemeteries in this region. The U.S. Regulars section at Gettysburg contains a single United States Colored Troops (USCT) grave, and Antietam National Cemetery includes no USCT graves at all. Most of the region’s African American Civil War veterans rest instead at local cemeteries, such as Williamsport’s Riverview Cemetery, where three USCT are buried; and in African American cemeteries, such as Ebenezer African Methodist Episcopal Church cemetery in Hagerstown and Fairview United Methodist Church near Taylorsville in Carroll County, each of which holds the remains of six USCT. The Zion Union Cemetery in Mercersburg in Franklin County, PA, is the final resting place for at least thirty-six USCT veterans from that town, and at least thirty USCT veterans are buried in Lincoln Cemetery in Gettysburg.

The major battles in the region required the Union states of Maryland and Pennsylvania to bury thousands of Confederate dead. In Shepherdstown, West Virginia (still part of Virginia when the conflict began) the local Southern Soldier’s Memorial Association purchased a plot for the Confederate dead in Elmwood Cemetery in 1868, and soon unveiled a monument to the unknown dead, whose deeds “are not forgotten.” At Gettysburg, Confederate trench graves lay untended until Southern women’s groups paid to remove the remains to Richmond, Raleigh, Savannah, and Charleston in the 1870s. In 1870 the Maryland legislature chartered the Washington Confederate Cemetery in Hagerstown for burial of the exhumations from Antietam and South Mountain; former Confederate General Fitzhugh Lee presided at dedication ceremonies on June 15, 1877. Headstones honoring 302 Confederate soldiers – casualties of battles at South Mountain, Antietam, Gettysburg and Monocacy, and ill or wounded Southerners who died in local hospitals – line a stone wall on the edge of Mount Olivet Cemetery in Frederick. Another 408 unidentified Confederates who died during or following the Battle of Monocacy are buried in a mass grave at Mount Olivet.

Not all Civil War soldiers who perished during the war in mid-Maryland and the surrounding region fell on its great battlefields. Soldiers died by ones and twos from sunstroke or disease on the march, while others perished in isolated skirmishes. Near Greencastle, a lone stone obelisk preserves the memory of Corporal William H. Rihl of the 1st New York Cavalry, the first Union soldier to die opposing Lee’s advance into Pennsylvania in June 1863. Along PA Route 16 east of McConnellsburg, the graves of Privates William B. Moore and Thomas Shelton of the 18th Virginia Cavalry, who also fell in June 1863, remain decorated with small Confederate flags even today, along with a monument erected by the Daughters of the Confederacy in 1929.

All these sites invariably became the focal point of commemoration ceremonies during the immediate postwar years as the veterans honored the memory of their comrades in arms. Memorial Day ceremonies, hosted first by Union and Confederate veterans’ organizations and later continued by tradition and community spirit, drew appreciative crowds until after the World War II years. Then the crowds became smaller, and a few of the burial grounds fell into disrepair. Yet each headstone still represents the final resting place of a soldier whose life was cut short by the war.

Memory in Granite, Marble, and Bronze

The smoke of battle barely had dissipated when the erection of monuments and memorials began. The effort has continued practically until the present day, and the result is that the mid-Maryland and surrounding region is rich in Civil War monuments that commemorate a wide variety of Civil War era experiences.

Funereal monuments in the region appeared almost immediately after Appomattox and honored individual or community war dead. They  appeared in cemeteries or other community gathering places, generally retained a highly sectional tone, and ranged in size from small cenotaphs to elaborate and highly artistic tributes. Maryland’s first such marker, erected in 1866, tops the Catonsville grave of Captain John P. Gleeson of the 5th Maryland Infantry, a prisoner of war who died in Richmond in 1863, and salutes him as “a martyr to the cause of human liberty.” Upturned cannons, called mortuary cannons, mark the spots where Union and Confederate generals fell at Antietam. Among the very first (1889) and very last (1993) monuments to be dedicated on the South Mountain battlefield commemorate the deaths of Union General Jesse Reno and Confederate General Samuel Garland, Jr. Elaborate tributes with high artistic merit include the Private Soldier Monument (or “Old Simon” as he is known locally) at Antietam National Cemetery, and the Soldiers National Monument, dedicated at the center of Gettysburg National Cemetery’s semicircles of Union graves. Nearby is Gettysburg’s first “portrait statue,” a life-sized bronze likeness of fallen Union General John F. Reynolds, dedicated in 1871. Well into the early twentieth century, these monuments became the site of highly partisan Memorial Day ceremonies, with Grand Army of the Republic camps hosting Memorial Day proceedings on May 30 and Southern veterans’ groups holding similar rites in early June.

appeared in cemeteries or other community gathering places, generally retained a highly sectional tone, and ranged in size from small cenotaphs to elaborate and highly artistic tributes. Maryland’s first such marker, erected in 1866, tops the Catonsville grave of Captain John P. Gleeson of the 5th Maryland Infantry, a prisoner of war who died in Richmond in 1863, and salutes him as “a martyr to the cause of human liberty.” Upturned cannons, called mortuary cannons, mark the spots where Union and Confederate generals fell at Antietam. Among the very first (1889) and very last (1993) monuments to be dedicated on the South Mountain battlefield commemorate the deaths of Union General Jesse Reno and Confederate General Samuel Garland, Jr. Elaborate tributes with high artistic merit include the Private Soldier Monument (or “Old Simon” as he is known locally) at Antietam National Cemetery, and the Soldiers National Monument, dedicated at the center of Gettysburg National Cemetery’s semicircles of Union graves. Nearby is Gettysburg’s first “portrait statue,” a life-sized bronze likeness of fallen Union General John F. Reynolds, dedicated in 1871. Well into the early twentieth century, these monuments became the site of highly partisan Memorial Day ceremonies, with Grand Army of the Republic camps hosting Memorial Day proceedings on May 30 and Southern veterans’ groups holding similar rites in early June.

A second partisan theme, emerging first in the late 1860s, commemorated the sacrifice of survivors, including veterans’ monuments on town squares, regimental monuments on battlefields, and tributes to Northern or Southern women. The most active period for the dedication of unit memorials at Gettysburg fell between 1885 and 1895; monumentation at Antietam saw its greatest activity in the period from 1900 to 1910. Battlefield monuments ranged from grand state monuments to understated regimental markers representing honors extended by individual counties or towns. “State Days” for monument dedications drew huge crowds. Attendees at Maryland Day ceremonies at Gettysburg on October 25, 1888 witnessed a series of monument unveilings for Maryland Union regiments that served on Culp’s Hill and elsewhere on the field. Pennsylvania Day at Antietam on September 17, 1904 included the dedications of a number of monuments to state units that fought in the battle forty-two years earlier, including one to the 51st Pennsylvania Infantry that stormed Burnside’s Bridge. At a Pennsylvania Day commemoration at Antietam two years later, a cluster of individual monuments were dedicated that honored Pennsylvania Reserve regiments near the North Woods. Even more often, however, individual regimental associations hosted their own ceremonies. At Monocacy in 1907, a small but respectful audience witnessed the dedication of a monument to the 14th New Jersey Infantry, which suffered heavily there.

The erection of Confederate monuments on battlefields in Northern states stirred controversy. In 1886, the veterans of the 2nd Maryland Infantry, C.S.A, decided to place a monument on Culp’s Hill at Gettysburg. Initially, the Gettysburg Battlefield Memorial Association (GBMA), which held authority over such placements, opposed the notion, but the former Confederate Marylanders persisted in their effort. On November 19, 1886 they arrived in great numbers from Baltimore and Frederick to dedicate their monument, completing what orator George Thomas, the regiment’s adjutant who had fallen wounded at Gettysburg, described as “a most sacred duty.” This would be the last Confederate monument erected at Gettysburg until the early twentieth century.

Beginning in the 1880s, the spirit of national reconciliation that inspired great reunions of Union and Confederate veterans at Gettysburg and Antietam was extended to national monuments that saluted the courage of both North and South. In 1884, the Gregg Cavalry Shaft on East Cavalry field at Gettysburg was dedicated, honoring the cavalry of both armies. In 1887, the Pickett’s Division Association planned to dedicate a memorial on Cemetery Ridge where Pickett’s Charge crested. When the GBMA refused to permit another Southern monument so close to the Union lines, the Virginians threatened to boycott a long-planned reunion with the Philadelphia Brigade they had fought on July 3, 1863. To resolve the impasse, the Philadelphians sponsored a marker inside their own lines honoring Brigadier General Lewis A. Armistead, one of Pickett’s fallen brigade commanders, and dedicated it to the “glory of the American volunteer soldier,” without regard to section. The first state monument on any local battlefield that commemorated the services of both its Union and Confederate commands was the Maryland monument at Antietam, dedicated on May 30, 1900.

The commemorative era of Civil War monumentation that began with the passing of the wartime generation continues to the present day. As recently as 1995, Maryland dedicated its state monument at Gettysburg, one that  features a Union soldier supporting a wounded Confederate, starkly contrasting with the partisan monuments the veterans built in the 1880s. In recent years, Gettysburg has hosted dedication ceremonies for monuments to Delaware troops, General Longstreet, and the 11th Mississippi. In 1997, a memorial to the Irish Brigade was dedicated near the Bloody Lane at Antietam. Both parks have now declared an end to future monumentation.

features a Union soldier supporting a wounded Confederate, starkly contrasting with the partisan monuments the veterans built in the 1880s. In recent years, Gettysburg has hosted dedication ceremonies for monuments to Delaware troops, General Longstreet, and the 11th Mississippi. In 1997, a memorial to the Irish Brigade was dedicated near the Bloody Lane at Antietam. Both parks have now declared an end to future monumentation.

Not all of the region’s Civil War monuments commemorate the memory of its warriors. The imposing War Correspondents Arch on the Crampton’s Gap battlefield, dedicated in 1896, salutes the service of the reporters and artists who described the events of the war in narrative and picture. Late in the nineteenth century the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad Company erected an obelisk alongside its tracks at Harpers Ferry to mark the original location of John Brown’s Fort. In 1914 a monument to Barbara Fritchie, who in 1862, according to the John Greenleaf Whittier poem and local legend, defiantly waved a U.S. flag at Stonewall Jackson and his men, was erected in Frederick’s Mount Olivet Cemetery. In 1962, during the Civil War Centennial, a Clara Barton monument was dedicated at Antietam Battlefield. This commemorated her care of the wounded during the war’s bloodiest day. In Frederick, a historical marker about the Dred Scott Supreme Court decision of 1857 was erected in 2009 next to an older bust of Roger Brooke Taney, the Chief Justice who authored the majority opinion in the case. A monument also stands in Emmitsburg about a battle that did not take place. Preceding the Battle of Gettysburg, as soldiers began piling into Emmitsburg, there was some alarm among the Daughters of Charity that a huge battle might take place on and around their grounds in Emmitsburg. When that battle occurred north of town instead, the sisters erected the Our Lady of Victory statue giving thanks that Emmitsburg was spared.

The selective memory of the Civil War, as displayed in bronze and granite in this border region, continues to illustrate the slow healing process that followed the end of hostilities. Noticeable by their absence are memorial tributes to the contributions of USCT soldiers. This oversight is being corrected in some places.

The Enduring Bonds of Brotherhood: Civil War Veterans Groups

Almost as soon as the Civil War ended, many veterans of both armies quickly discovered that they missed military life. The emergence of veterans groups as early as 1865 replicated their wartime affiliations, and whether their cause ended in victory or defeat, former combatants reorganized along quasi-military lines to offer mutual support and to perpetuate the memory of their cause and of their fallen comrades.

Maryland’s Union soldiers began organizing while still in ranks. On April 9, 1865, on the front lines at Appomattox, survivors of the Army of the Potomac’s Maryland Brigade established the Union Veteran Association of Maryland. In time, this group renamed itself the Social Club of the Loyal Maryland Line and remained active for the next sixty-five years. Veterans of several Pennsylvania units also established regimental associations before they mustered out. The new Military Order of the Loyal Legion for commissioned officers and the National Association of Naval Veterans, formed in New York in 1887, quickly numbered this region’s veterans in their ranks as well.

The most influential of all Union veterans groups was the Grand Army of the Republic (GAR), organized on April 6, 1866. The GAR recognized each state as a department composed of community-based posts called “camps.” Maryland alone organized eighty-two camps, and by the 1880s GAR camps could be found even in the South. Members of GAR posts actively lobbied for veteran pensions and other benefits and officiated at local commemorative events. The Women’s Relief Corps (WRC), organized in 1879, provided the GAR with a ladies auxiliary devoted to raising funds for monumentation efforts and sponsoring civic and educational activities to perpetuate the memory of those who served in the Union army.

Individual GAR posts usually adopted the name of a local war hero. Thus, Pennsylvania Camp No. 9 in Gettysburg took the name of Corporal Johnston H. Skelly, a local soldier in the 87th Pennsylvania who fell at  Winchester in June 1863. GAR posts were formed in Hagerstown, Frederick, Westminster, Thurmont, Emmitsburg (two), Smithsburg, Keedysville, Sharpsburg and Hancock (two). Franklin County in Pennsylvania had seven posts and four were formed in Gettysburg. Posts also existed in Martinsburg, Harpers Ferry, and Berkeley Springs in West Virginia. African American veterans also formed GAR posts, since most white posts around the country did not allow African American members. African American posts were created in Hagerstown, Frederick, New Windsor, and Chambersburg. The GAR peaked in numbers and influence in the 1880s and 1890s but continued to exist until the deaths of the last Union veterans in the 1950s. Today, visitors to the mid-Maryland border region’s cemeteries can still spot star-shaped GAR insignia on the flag-holders over Union veterans’ graves.

Winchester in June 1863. GAR posts were formed in Hagerstown, Frederick, Westminster, Thurmont, Emmitsburg (two), Smithsburg, Keedysville, Sharpsburg and Hancock (two). Franklin County in Pennsylvania had seven posts and four were formed in Gettysburg. Posts also existed in Martinsburg, Harpers Ferry, and Berkeley Springs in West Virginia. African American veterans also formed GAR posts, since most white posts around the country did not allow African American members. African American posts were created in Hagerstown, Frederick, New Windsor, and Chambersburg. The GAR peaked in numbers and influence in the 1880s and 1890s but continued to exist until the deaths of the last Union veterans in the 1950s. Today, visitors to the mid-Maryland border region’s cemeteries can still spot star-shaped GAR insignia on the flag-holders over Union veterans’ graves.

Confederate veterans also organized almost immediately after the war. With the goals of honoring their fallen comrades, providing aid to needy comrades, and preserving records for a “truthful history” of the war, the Society of the Army and Navy of the Confederate States in the State of Maryland was formed in 1871. In 1870 the Association of the Army of Northern Virginia was organized, with Jubal A. Early serving as president. Former Frederick attorney and Confederate General Bradley T. Johnson was chairman of the Executive Committee, while Isaac Ridgeway Trimble led the Maryland Division. In 1880, the Association of the Maryland Line was established to further the work of preserving the history of Maryland’s Confederate command, and in part to maintain the Maryland Line Confederate Soldiers’ Home at Pikesville. By the time the United Confederate Veterans (UCV) emerged as the primary veterans group for Southern veterans in 1889, it built on a strong foundation of Southern veteran activity in Maryland.

Like the GAR, the UCV set up state-level divisions composed of individual camps. At least two UCV camps, one named for partisan ranger John Singleton Mosby and one for Ball’s Bluff casualty Clinton Hatcher, operated in Leesburg. Charlestown, WV, had one UCV camp. Mid-Maryland hosted one UCV camp: No. 500 Alexander Young Camp in Frederick. A total of eleven UCV camps became active in the Maryland Division. Confederate veterans in south-central Pennsylvania joined Maryland posts or the UCV camp in Philadelphia. The United Daughters of the Confederacy (UDC) organized in 1894, and at least twenty-two chapters became active in Maryland alone, dedicated to the same kinds of activities embraced by their Union counterparts, the Women’s Relief Corps.

As individuals and as organized groups, Civil War veterans frequently visited battlefields in the mid-Maryland border region. Northerners returned in substantial numbers first. By the early 1880s, the Pennsylvania GAR frequently held annual reunions at Gettysburg. During the 1880s and 1890s, they came by the hundreds to dedicate their monuments at Antietam, Gettysburg, and Monocacy. In a well-publicized visit in 1886, the veterans of the 15th Massachusetts Infantry made a grand tour of three of their most costly battles: Ball’s Bluff, Antietam, and Gettysburg.

Beginning in the 1880s, joint reunions of the Blue and Gray became increasingly more frequent. In July 1887, the survivors of the Army of the Potomac’s Philadelphia Brigade and the Pickett’s Division Association led the way when they agreed to meet at Gettysburg, where they had clashed in “Pickett’s Charge.” Some hardliners on both sides loudly opposed such ventures, but by the time of the golden anniversary reunion at Gettysburg in 1913, over 50,000 veterans from both armies witnessed a re-enactment of “Pickett’s Charge” by cane-wielding Southerners that concluded with handshakes across the stone wall at the Angle.

Beginning in the 1880s, joint reunions of the Blue and Gray became increasingly more frequent. In July 1887, the survivors of the Army of the Potomac’s Philadelphia Brigade and the Pickett’s Division Association led the way when they agreed to meet at Gettysburg, where they had clashed in “Pickett’s Charge.” Some hardliners on both sides loudly opposed such ventures, but by the time of the golden anniversary reunion at Gettysburg in 1913, over 50,000 veterans from both armies witnessed a re-enactment of “Pickett’s Charge” by cane-wielding Southerners that concluded with handshakes across the stone wall at the Angle.

The last great reunions of Civil War veterans took place in this border region. Veterans at Antietam in 1937 witnessed the National Guard reenacting the Bloody Lane phase of the battle and received pins featuring the symbolic handshake that represented the termination of ill will between Blue and Gray. The next year at Gettysburg, more than 1,800 veterans from both armies, who averaged over ninety years of age, watched President Franklin D. Roosevelt unveil the Peace Light Memorial.

The Sons of Veterans of the United State of America was organized in 1881, with its membership restricted to direct descendants of Union Veterans. In 1925 it changed its name to Sons of Union Veterans of the Civil War (SUV). With the demise of the GAR, occasioned when the last Civil War veterans died in the 1950s, the SUV became the GAR’s legally recognized representative and heir. In its federal charter, which was granted in 1954, the organization’s first stated purpose was: “To perpetuate the memory of the Grand Army of the Republic and of the men who saved the Union in 1861 to 1865.” The Sons of Confederate Veterans was organized on July 1, 1896. Membership was restricted to male descendants, direct or collateral, of a Confederate soldier. It provides social and educational events and honors the memory of former Confederates.

All the old veterans are gone now, as are Maryland’s GAR and UCV chapters. But the legacy of the region’s vibrant veterans’ community remains alive today as active camps of the Sons of Union Veterans and Sons of Confederate Veterans and their auxiliary groups strive to preserve the heritage of their Civil War ancestors.

Preservation of Battlegrounds

Mid-Maryland and the surrounding region features five major Civil War battlegrounds open to public visitation today – Gettysburg, Antietam, Monocacy, Ball’s Bluff, and South Mountain, as well as a national historical park – Harpers Ferry – that interprets a number of Civil War battles and events. The development of each represents its own unique blending of the forces of history and memory.

The smoke barely had cleared at Gettysburg when the newly-formed Gettysburg Battlefield Memorial Association (GBMA) purchased acreage held by the victorious Union army on Culp’s Hill, Cemetery Hill, and Little Round Top. Further development languished until the 1880s, however, when growing interest from the Grand Army of the Republic and the crusading zeal of John B. Bachelder, Gettysburg’s first “official historian,” reinvigorated the GBMA’s land acquisition efforts. Southerners rarely revisited the field of their greatest defeat, especially since early monumentation and interpretation focused almost entirely on the Union positions. As the GBMA’s authority on accurate placement of monuments, Bachelder clashed repeatedly with veterans whose long-cherished memories were at odds with his own (usually) objective reading of the historical record. Indeed, the veterans of the 72nd Pennsylvania infantry successfully sued the GBMA to overturn Bachelder’s decision that placed their monument with others on the main Union battle line rather than at a spot they preferred, one much closer to the famed stone wall where they advanced to repulse Pickett’s charge. By the 1890s, the historical integrity of the battlefield faced a new threat: a wide range of commercial ventures. This  prompted New York Congressman Daniel E. Sickles to sponsor legislation in 1895, known as the “Sickles Act,” creating Gettysburg National Military Park and transferring its administrative authority to the War Department. The observation towers for military instruction and the black-and-white narrative plaques written by Union and Confederate veterans in non-partisan tones remain today’s most obvious legacies of the War Department’s administration. By the golden anniversary celebration in 1913, with Confederate lines now marked and plans underway for Southern state monuments, Gettysburg truly had become a national battlefield. In 1933, the National Park Service took over the administration of the park. In recent years, the cause of historical accuracy has won significant victories through the action of dedicated park administrators, aided by the financial support of non-profit groups, who have led efforts to remove commercial intrusions such as the National Tower, to bury unsightly utility lines, to remove non-historical tree growth, and to replant orchards. All of this is aimed at restoring the battlefield terrain as closely as possible to that of 1863.

prompted New York Congressman Daniel E. Sickles to sponsor legislation in 1895, known as the “Sickles Act,” creating Gettysburg National Military Park and transferring its administrative authority to the War Department. The observation towers for military instruction and the black-and-white narrative plaques written by Union and Confederate veterans in non-partisan tones remain today’s most obvious legacies of the War Department’s administration. By the golden anniversary celebration in 1913, with Confederate lines now marked and plans underway for Southern state monuments, Gettysburg truly had become a national battlefield. In 1933, the National Park Service took over the administration of the park. In recent years, the cause of historical accuracy has won significant victories through the action of dedicated park administrators, aided by the financial support of non-profit groups, who have led efforts to remove commercial intrusions such as the National Tower, to bury unsightly utility lines, to remove non-historical tree growth, and to replant orchards. All of this is aimed at restoring the battlefield terrain as closely as possible to that of 1863.

The creation of Antietam National Battlefield took a slightly different approach, and the “Antietam” plan and the “Gettysburg” plan would provide the two standard models for land acquisition at Civil War battlefields. While individual veterans groups started buying small parcels of land at Antietam for regimental monuments by the mid-1880s, Congress took the lead in August 1890 by appropriating funds to survey and preserve the battle lines of both armies. The War Department administered the site beginning in 1894. Land acquisition was not a high priority, however. The federal government purchased only narrow strips of land for rights-of-ways to build roads to the key sites of the hardest fighting and an interpretive tower at the Bloody Lane. An Antietam Battlefield Board supervised the researching, writing, and positioning of great numbers of textual tablets that explained in detail the movements of the armies. Five iron tablets were also placed at Harpers Ferry to commemorate the role of the town in the Antietam Campaign. Although the committee ceased operation in 1898, board member Ezra A. Carman, a Union veteran and Antietam’s counterpart to John Bachelder, continued to research and correct the historical narrative on panels for nearly a decade more. Many of these original panels still stand today. Like Gettysburg, Antietam came under the administration of the National Park Service in 1933. While it never experienced Gettysburg’s assault from development and commercial pressure, large tracts of key terrain at Antietam remained in private hands for years, including the Miller Cornfield (acquired in 1990) and the Roulette farm (acquired in 1998). Aggressive land acquisition efforts and successful grantsmanship has resulted in the addition of these new park holdings and more in the past two decades. The non-profit Save Historic Antietam Foundation (SHAF) actively supports educational programs and projects that promote its mission to preserve and protect historic sites related to the Battle of Antietam and the broader Maryland Campaign of 1862.

Civil War veterans dedicated a few monuments or held small reunions at Monocacy, South Mountain, and Ball’s Bluff, but they did not mount significant efforts to preserve these battlefields. The political and fiscal commitment of succeeding generations, often based on local support, would save these historical sites.  Glenn Worthington, whose family owned part of the Monocacy battlefield, led the effort in 1929 to win congressional approval for its preservation. On June 21, 1934, Monocacy National Military Park was established by an act of Congress, although development was contingent upon land being donated to the government at no expense. Land acquisition progressed slowly and Interstate Highway 270 bisected the heart of the battlefield. In 1973 it was declared a National Historic Landmark, and, finally, in 1976, Congress appropriated money for land acquisition and changed the park’s name to Monocacy National Battlefield. South Mountain had to wait much longer for preservation efforts. Although veterans dedicated several monuments there in the 1880s, little energy went into the preservation of the battlefield until the Central Maryland Heritage League, established in 1989, led the efforts to acquire and interpret South Mountain battlefield acreage. The three major areas of fighting at South Mountain now comprise South Mountain State Battlefield, administered by the state of Maryland.

Glenn Worthington, whose family owned part of the Monocacy battlefield, led the effort in 1929 to win congressional approval for its preservation. On June 21, 1934, Monocacy National Military Park was established by an act of Congress, although development was contingent upon land being donated to the government at no expense. Land acquisition progressed slowly and Interstate Highway 270 bisected the heart of the battlefield. In 1973 it was declared a National Historic Landmark, and, finally, in 1976, Congress appropriated money for land acquisition and changed the park’s name to Monocacy National Battlefield. South Mountain had to wait much longer for preservation efforts. Although veterans dedicated several monuments there in the 1880s, little energy went into the preservation of the battlefield until the Central Maryland Heritage League, established in 1989, led the efforts to acquire and interpret South Mountain battlefield acreage. The three major areas of fighting at South Mountain now comprise South Mountain State Battlefield, administered by the state of Maryland.

Ball’s Bluff’s battlefield lay nearly forgotten, too, until the federal government preserved core battleground by acquiring the 4.63 acres around the cemetery in 1904. This site languished until the Civil War Centennial, when ceremonies in October 1961 brought together representatives from Mississippi, New York, Pennsylvania, Virginia, and Massachusetts, the states whose regiments fought there, and Oregon, the state that Col. Edward Baker, who was killed during the battle, represented in the U.S. Senate. On August 18, 1984, Ball’s Bluff battlefield won designation as a National Historic Landmark, with greatly enhanced interpretive paths and markers.

Despite being the site of the largest surrender of Union forces during the war, and the role it played in other battles and military campaigns, Harpers Ferry was not among the thirty-four military parks proposed between 1901 and 1904. “Harpers Ferry Historic Site” was approved by the U.S. Department of the Interior contingent upon the donation of land as per the Historic Sites Act of 1935. That same year Representative Jennings Randolph of West Virginia introduced a bill to establish Harpers Ferry National Military Park, but it was referred back for modification. Eight years later, as momentum increased to designate the site a national monument, Randolph introduced a bill to create the monument as a “public memorial commemorating Harpers Ferry campaigns of the War between the States (Civil War) and the great cause of human freedom.” The language of the bill was later modified so as to establish the location as a monument to “historical events at or near Harpers Ferry” generally. The legislation was passed by Congress and signed by President Roosevelt in 1944. It was not until 1951, however, that the states of West Virginia and Maryland appropriated money to acquire land that would formally establish the site. West Virginia acquired property the following year and presented it to the U.S. in a ceremony in Charleston on January 16, 1953. Maryland’s acquisition of land on Maryland Heights was not completed until 1965. The site became Harpers Ferry National Historical Park on May 29, 1963.

Gettysburg, Antietam, Monocacy, and Harpers Ferry all maintain substantial visitor centers. Until recently, the exhibits and programs in the battlefield parks promoted the theme of national reunion, with near-iconic photographs of elderly Union and Confederate veterans shaking hands across a stonewall. Since 2000, however, Congress has enjoined the National Park Service to restore discussion of the causes and consequences of the Civil War, and all of the region’s battlefield parks have made substantial efforts to introduce the themes of race, slavery, emancipation, and civil rights into their public displays and field programs. The lively, and occasionally heated, public commentary that often results from consideration of these themes continues to demonstrate the power of collective memory to preserve cherished traditions and beliefs.

Stories in Focus