Contextualizing American Slavery

Mathias de Sousa, a man “of mixed racial origins,” was among the first group of settlers who arrived in the newly-formed Province of Maryland in 1634. De Sousa was bound as the indentured servant of Jesuit priest Father Andrew White, who led the initial settlement in Maryland. Through the next several decades, enslaved and indentured people of African or Caribbean descent were a minority among the largely English and Irish bound laborers in Maryland. By 1664, however, just 32 years after the establishment of Maryland, the colonial government had codified racialized, chattel slavery. This came as the result of a developing plantation economy in the Chesapeake Bay region that was increasingly dependent upon enslaved African labor.

By the early 18th century, while the tobacco plantations around the Chesapeake Bay were thriving, the mountain and valley lands of central and western Maryland remained largely unexploited, occupied by small bands of Native Americans and a few European traders. These wild lands became a magnet for Maryland’s enslaved freedom seekers. In April 1720, Philip Thomas of Anne Arundel County petitioned the colonial General Assembly for the return of his enslaved “servant” who had “run away to the Tuskarora [sic] Indians who refuse to deliver the same.” In response, the Assembly ordered the Tuscarora, whose village was located on the Monocacy River, to “Deliver the said Servant or shew Cause why they detain him Contrary to the Treatie [sic] of Peace made with them last Assembly.” Two years later, the Assembly sought a similar treaty of “Friendship and Amity” with the Shawnee, who had villages along the upper Potomac River. The treaty included specific language “for their surrendering up to this Government certain Negro Slaves who for some time past have been entertain’d at their Towns upon Potomack River.” In 1725, the Assembly passed a fugitive slave law to incentivize the return of “run-away Slaves…brought in from the Back-Woods.” These treaties and laws failed to stem the westward tide of freedom seekers, however. In a 1729 deposition, a young enslaved woman named Eleanor Cusheca reported hearing from Harry who had escaped to “the Monocosy Mountains” and reported “there were many Negroes among the Indians at Monococy.”

These early efforts in Maryland, first to codify chattel slavery and then to prevent aid to those who would seek their freedom, mirrored similar efforts throughout the American colonies, both to the north and south of Maryland, that laid the foundation for nearly 250 years of slavery in America.

Even as Americans continue to debate the causes of the Civil War, the core of the dispute revolved around the institution of slavery in the United States and its territories. From the very start of the war the states that formed the Confederacy fought to preserve their right to sustain chattel slavery and to expand the institution across the western territories. This was made clear in Confederate Vice President Alexander H. Stephens March 1861 “Cornerstone Speech,” in which he declared, “…African slavery as it exists amongst us – the proper status of the negro in our form of civilization. This was the immediate cause of the late rupture and present revolution.” Of the four states – Georgia, Mississippi, Texas, and South Carolina – that published a “Declaration of Causes” following their vote to secede from the United States, all identified slavery as a central cause. The states fighting to preserve the Union, now split over this issue, would coalesce around the cause of ending slavery by 1863, compelled by the tide of African American freedom seekers and the political imperative of President Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation.

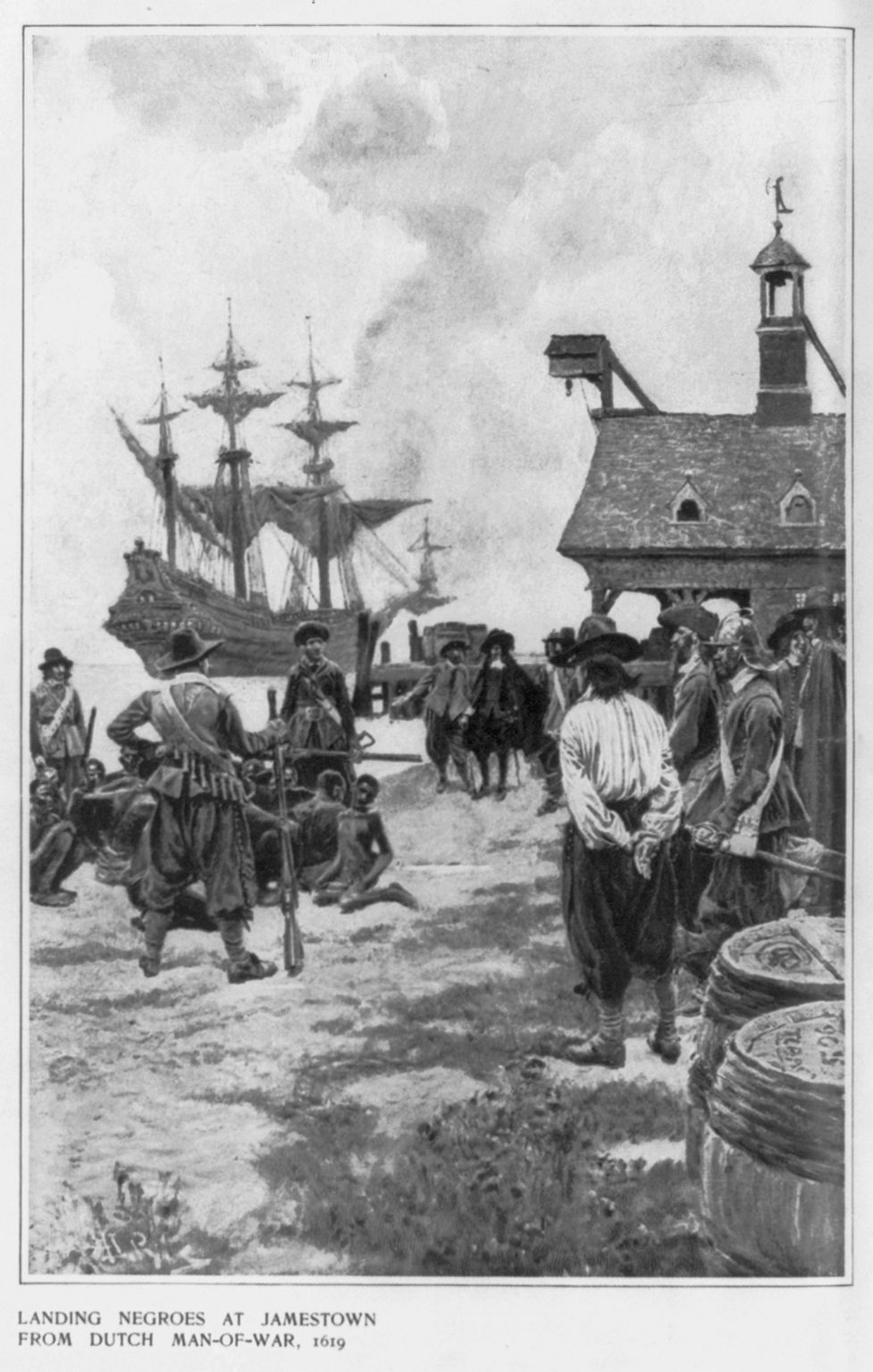

Despite the divide over slavery that in 1861 precipitated the American Civil War, the modern perception of the “slave south” and “free north” division as “the way things were,” obscures the deeper history of slavery in the United States. From the earliest colonial settlements in both the Virginia and Massachusetts colonies, enslaved African people were forced to labor. The earliest documentation of Africans brought to American soil was recorded by John Rolfe in 1619, when “20 and odd Negroes” (20+) were sold to the Jamestown authorities by a Dutch trade ship in exchange for needed supplies.

In the northern colony of Massachusetts, colonial governor John Winthrop documented the arrival of “negroes” on the ship Desire in 1638. The ship, which had sailed from Salem, Massachusetts to the West Indies carrying “captive Indians…for sale as slaves” and returned with a cargo of enslaved Africans, is described by historian Wendy Warren as “the first known slaving voyage to and from New England.”

Though enslaved African people were clearly present on American soil from very early in colonial development, the bulk of bound labor involved indentured, or time-limited, servitude. Initially, most indentured servants were landless peasants from England. Unable to pay for their passage to America, ship captains transported them in exchange for the sale price of their labor contracts (indentures). The men, women, and children who were sold on the docks of port towns along the East Coast and bound by these indentures, filled the need for cheap laborers in the difficult frontier conditions of the early colonial era. By the middle of the 17th century, wealthy landowners, particularly from the Chesapeake region and Carolinas, began a shift to enslaved African people as a more reliable source of long-term forced labor.

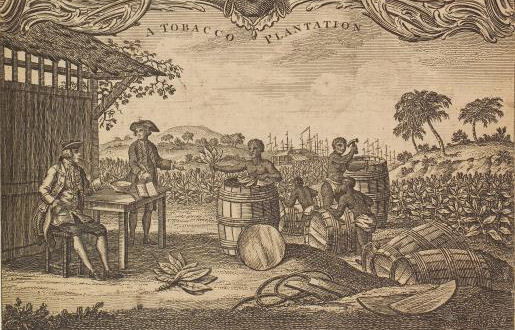

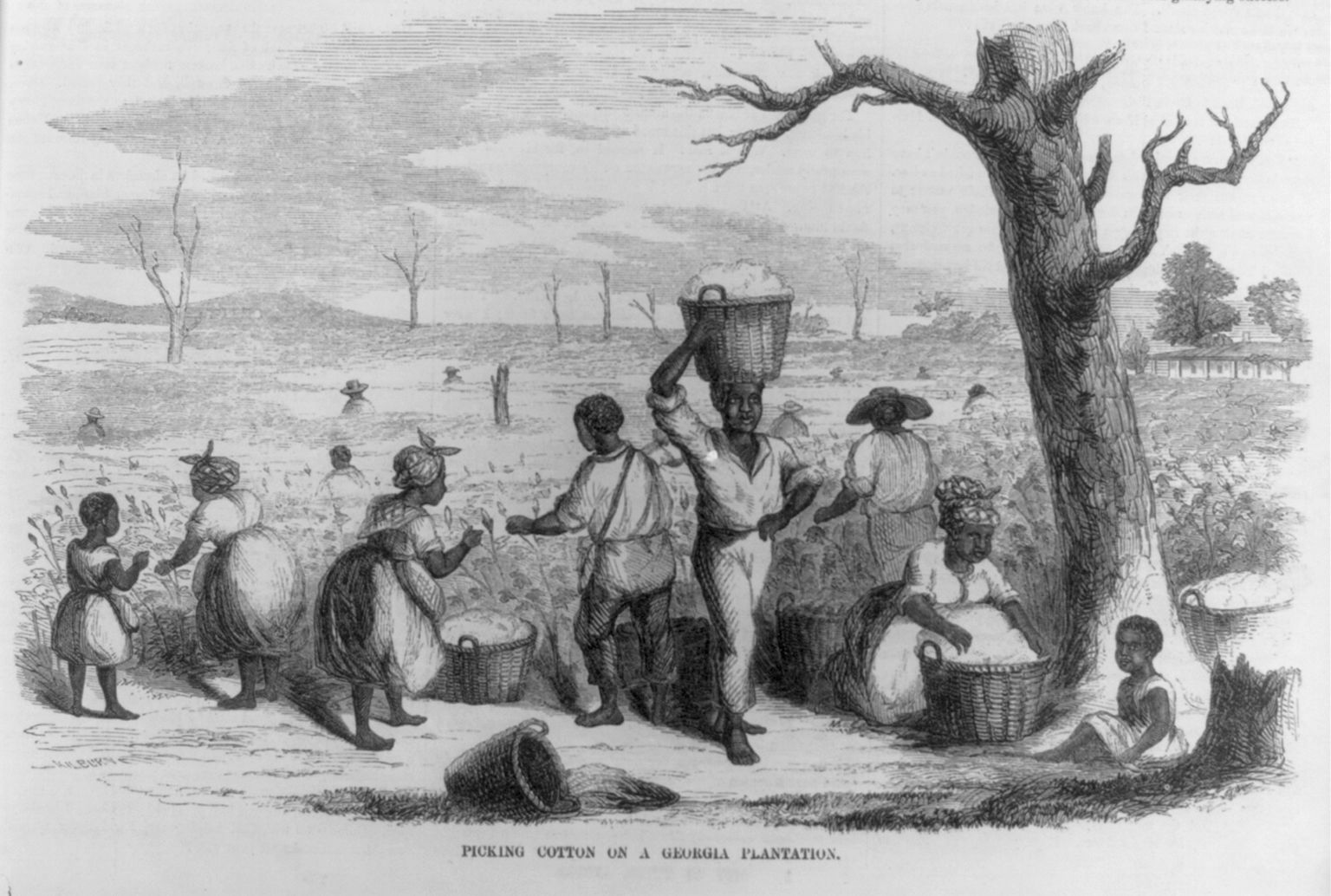

The southern colonies, including Maryland, Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina, and Georgia largely prospered through the first half of the 18th century under the extensive cultivation of cash crops, particularly tobacco, indigo, and rice. These large-scale, labor-intensive crops drove the market for enslaved labor throughout the region. Population data compiled in 1776 recorded the following enslaved populations in the southern colonies/states: “Delaware 9,000; Maryland 80,000; Virginia 165,000; North Carolina 75,000; South Carolina 110,000; and Georgia 16,000.” By the time of the first US Population Census in 1790, Virginia’s enslaved population had swelled to nearly 300,000 (39 percent of its total population), North Carolina enumerated 100,500 enslaved (25.5 percent), South Carolina’s rice plantations accounted for 107,000 enslaved people (43 percent), Georgia had just over 29,000 (35.5 percent), and Maryland listed 103,000 enslaved (32 percent of the total Maryland population).

To the north, the New England colonies, including New Hampshire, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, and Connecticut (later including the states of Maine and Vermont), and the Middle Atlantic colonies, including New York, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania (as defined by the US Census), developed their own economic dependence on enslaved labor. On the small farms scattered across the northern colonies, the labor of just one or two enslaved people, notes Marc H. Ross, “could double or triple the workforce during planting and harvest seasons.” The coastal plains of Rhode Island, Connecticut, and New York supported larger farming operations with larger numbers of enslaved laborers. The foodstuffs produced by the enslaved on northern farms, was sold to northern merchants and shipped to the Caribbean islands, eventually finding its way to the sugar plantations to feed the masses of enslaved laborers. The sugar produced by the enslaved on the island colonies returned to the northern port cities where rum was produced for sale overseas. Ships that sailed from northern ports were actively engaged in the movement of enslaved people, forming the well-known triangle of trade between North America, Africa, and the Caribbean.

Much of the New England economy revolved around the shipping industry. Men and women enslaved in coastal urban and rural town settings labored as “shipbuilders, dockworkers, sailors, tanners, coopers, iron founders, house builders, and the brute labor for public works projects.” This largely forgotten aspect of northern colonial history includes a surprising footnote: New York City reportedly had the largest urban enslaved population in the American colonies as late as 1750, while the combined number of rural and urban enslaved people in the tiny colony of Rhode Island accounted for 10 percent of its total population through the 1750s. The enumeration estimates from 1776 reveal still-significant numbers of enslaved men, women, and children in the northern colony/states: “Massachusetts 3,500; Rhode Island 4,373; Connecticut 6,000; New Hampshire 629; New York 15,000; New Jersey 7,600; and Pennsylvania 10,000.” The 1790 US Population Census reveals significant changes in the northern enslaved populations: Pennsylvania 3,707; Connecticut 2,648; Rhode Island 958; New Hampshire 157; Massachusetts 0. Only New York and New Jersey had increased, at 21,000 and 11,423 respectively.

The American Revolution impacted many Americans’ ideas about enslaved labor in the new nation founded on freedom, particularly in the northern states. Progress toward the abolition of slavery moved across the northeast region, beginning in 1777 with the new territory of Vermont, carved from New York, which proscribed slavery in its constitution. Slavery in Massachusetts was nullified by a court decision in 1781. Gradual emancipation of the enslaved in Pennsylvania was enacted in 1780, and in Connecticut and Rhode Island in 1784, effectively ending slavery in those states by the 1840s. New York passed a gradual emancipation bill in 1799, finally abolishing slavery on July 4, 1827. New Jersey enacted a gradual end to slavery in 1804. Then, in 1846, the legislature abolished slavery, but in a devious twist, reclassified all remaining bondspeople as “apprentices for life.” New Hampshire was last to legally abolish the institution of slavery in 1857, though between 1800 and 1840 only 4 people were listed in the census as enslaved.

Even in the northeastern states, however, freedom for African Americans did not translate to full citizenship, as Philadelphia historian Marc H. Ross observed, “there was no effort to integrate the free Black population into the social and economic fabric of Northern society.” While anti-slavery activists, both Black and white, aided freedom seekers along the fabled Underground Railroad, others sought the removal of free Black people from their resident states altogether.

The American Colonization Society (ACS) was established in 1816 in Washington, DC to encourage free African Americans to “return” to Africa. The ACS, with a membership that included enslavers, did not seek to abolish slavery. Rather, its purpose was to remove free Black people from American society. Though the ACS failed in its purpose, auxiliary chapters were established all over the United States.

While slavery was coming to an end in the New England and mid-Atlantic states, the system of forced labor continued to thrive in the states located below the Mason-Dixon Line, including Maryland. Despite the optics of emancipation and a growing anti-slavery movement in the northern states, it was enslaved labor in the southern states that powered an emerging American economy that benefited states on both sides of Mason and Dixon’s line. The trade triangle of the 18th century was strengthened in the early decades of the 19th century as the American Industrial Revolution dawned. By the 1830s, cotton cultivation in the southern states – heavily dependent upon enslaved labor – supplied the factories of Baltimore, Philadelphia, Paterson (NJ), New York City, and Lowell (MA), among others. Immigrant laborers in northern factories were fed by the grains produced by bondspeople in the Chesapeake region, then lauded as the breadbasket of the US. Land hungry cotton production prompted President Andrew Jackson’s 1830s policy of American Indian removal and fueled tensions in the disputed Texas territory leading to the Mexican-American War of 1846-1848. Territorial expansion and the extension of slavery would drive political discourse throughout the first half of the 19th century.

Politics of Slavery: “The Balance Principle”

From the earliest territorial expansions into the frontier claims of the original thirteen colonies through the large expanses of the Plains to the Pacific Coast, the political ramifications of institutionalized slavery reverberated across the decades of growth. Congress followed a carefully unofficial system for the creation of new states. “Balancing admission of free and slave states to the Union, what I term the ‘balance principle,’” observed historian Dr. Cheryl LaRoche, “was a critical aspect of the project of sectional equilibrium that maintained the balance between slave state and free.” In 1791, Vermont, a “free state,” was admitted to the Union following in 1792 by Kentucky, a “slave state”; Tennessee (1796, “slave”) was followed by Ohio (1803, “free”); and Louisiana (1812, “slave”) was followed by Indiana (1816, “free”). With the growing expanse of US territory this equilibrium began to unravel as “the landscape of the nation cleaved along an alternating North-South fault line.”

The movement toward abolishing slavery in the northern states and preventing its spread into the expanding US territories aggravated the sectional tension between free and slave states spawned after the American Revolution. The so-called “Compromise of 1850” was structured to abate some of that tension. While Congress admitted California to the Union as a “free state” to appease northern “free soilers,” it gave the southern slave states the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850,forcing citizens in free states to aid in the recovery and return of “fugitives from service or

labor.” Instead of relieving the tension, however, the compromise instead further hardened the divide between slave and free states. The sectional tension of the 1850s reached its apex in “bleeding Kansas.” Embroiled in the national debate over federal control of western territories, the Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854 effectively ended federal determination of slave or free territory, opening the Kansas and Nebraska territories to settlement and “the right of self-determination on the slave issue.”

Missouri enslavers quickly laid claim to southeastern Kansas border lands, but their numbers paled in the face of thousands of immigrants drawn by the promise of new land. The Kansas frontier attracted free-labor farmers, mostly from Ohio, Illinois, and Indiana. Others were European immigrants, as well as African American freemen and those who had escaped their bonds to seek freedom. Some settlers from New York and Massachusetts were abolitionists recruited by the New England Emigrant Aid Company of Boston, who founded the town of Lawrence, and the American Missionary Association from New York, who founded Osawatomie. Abolitionist settlers, including John Brown and James H. Lane, chose the hotly contested Kansas territory along the Missouri border to wage their war against slavery and actively aided freedom seekers from Missouri, solidifying the “free soil” future of Kansas. Kansas was admitted to the Union as a free state in January 1861, just a few months before the United States dissolved into Civil War.

Slavery and Freedom on the Maryland Border

(See “Firsthand Accounts” database for first-hand accounts)

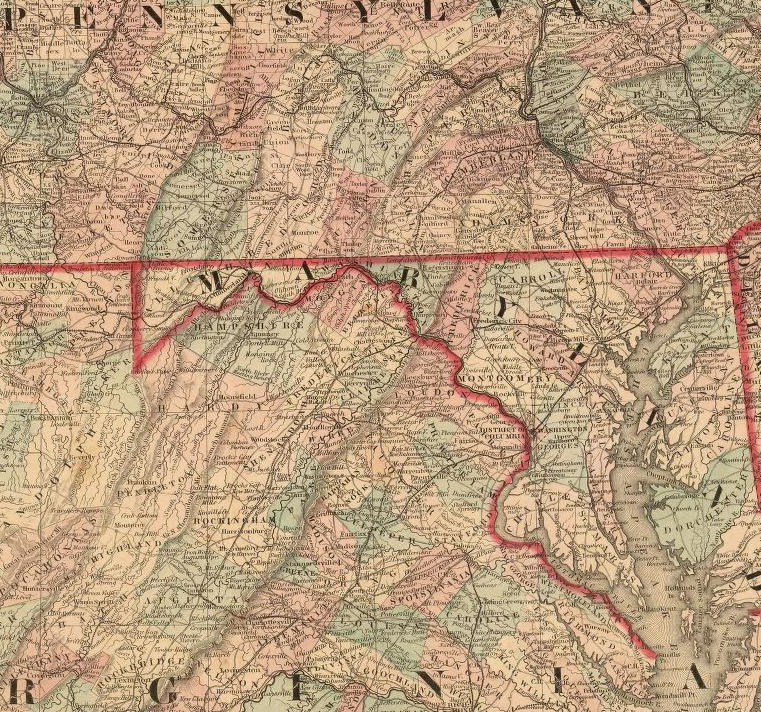

The African freedom seekers who found their way to the Catoctin Mountains in the 1720s to take refuge among the Native Americans, traveled long distances from the established region of colonial Maryland, then still concentrated along the shorelines of the Chesapeake Bay. Western shore planters, like those on the Eastern Shore, were tied to the tidal tributaries of the Chesapeake Bay for transportation. The tobacco they produced, the foundation of an increasingly lucrative economy, was grown on plantations located in Baltimore, Anne Arundel, Prince George’s, Calvert, Charles, and St. Mary’s counties.

In the early decades of the eighteenth century, the Prince George’s County boundary extended all the way to the largely unsettled western bounds of the Maryland colony. Much of that land was thought to be “barren” and unproductive. That would begin to change by the late 1720s as German migrants seeking land on which to establish smaller, grain-producing farms moved south from Pennsylvania to claim land in Virginia’s Shenandoah Valley. A few, noting the rich limestone soil in the valleys along the Catoctin and South Mountain ranges, determined to put down roots even before Maryland’s then-proprietor, Charles Calvert, Fifth Lord Baltimore, opened the land for settlement in 1732. Wealthy gentlemen living in the Chesapeake Bay region also jumped the opening date, securing large tracts from which they expected to sell or lease smaller parcels at a profit. By the middle of the 1730s, German farmers from Pennsylvania, and the sons of English planters from eastern Maryland who brought along their enslaved African laborers, would begin to populate the west-central frontier region.

Slavery on the Border

Slavery in Maryland varied in its application as widely as the diverse geographical regions of the state. Ethnic, religious, and ultimately the political differences of the regional populations further emphasized the geographic and economic divisions. All of these variables shaped not only the characteristics of slavery as it was applied in the various Maryland regions, but also the gradual state-wide move away from the institution toward free labor. Between 1790 and 1860, the enslaved population in Maryland as a whole declined. At the same time, the free Black population increased due to manumissions and free births (children of free women were born free), and to a small extent from fugitives from the South.

Maryland farms on the Eastern Shore and southern Maryland principally focused on the cultivation of tobacco. A labor-intensive crop, tobacco production occupied enslaved laborers throughout much of the year. In these regions, where wealthy English or Scotch-Irish families were the primary landowners, the social and economic composition closely resembled that of their southern neighbors in Virginia. Northern and western Maryland, including Washington, Frederick, and later Carroll County, was largely settled by German immigrants and their descendants migrating from Pennsylvania. Small grains such as wheat, oats, corn, and rye formed the basis of the region’s agricultural production. The seasonal requirements of grain farming demanded fewer laborers through much of the year. Free Black and immigrant day laborers formed the core of the labor force, supplemented by significantly smaller numbers of enslaved people in these regions. Comparison of the enslaved labor populations in the mid-Maryland counties with those in St. Mary’s County in southern Maryland in 1790 illustrates the dramatic difference between the regions, as shown in the following table:

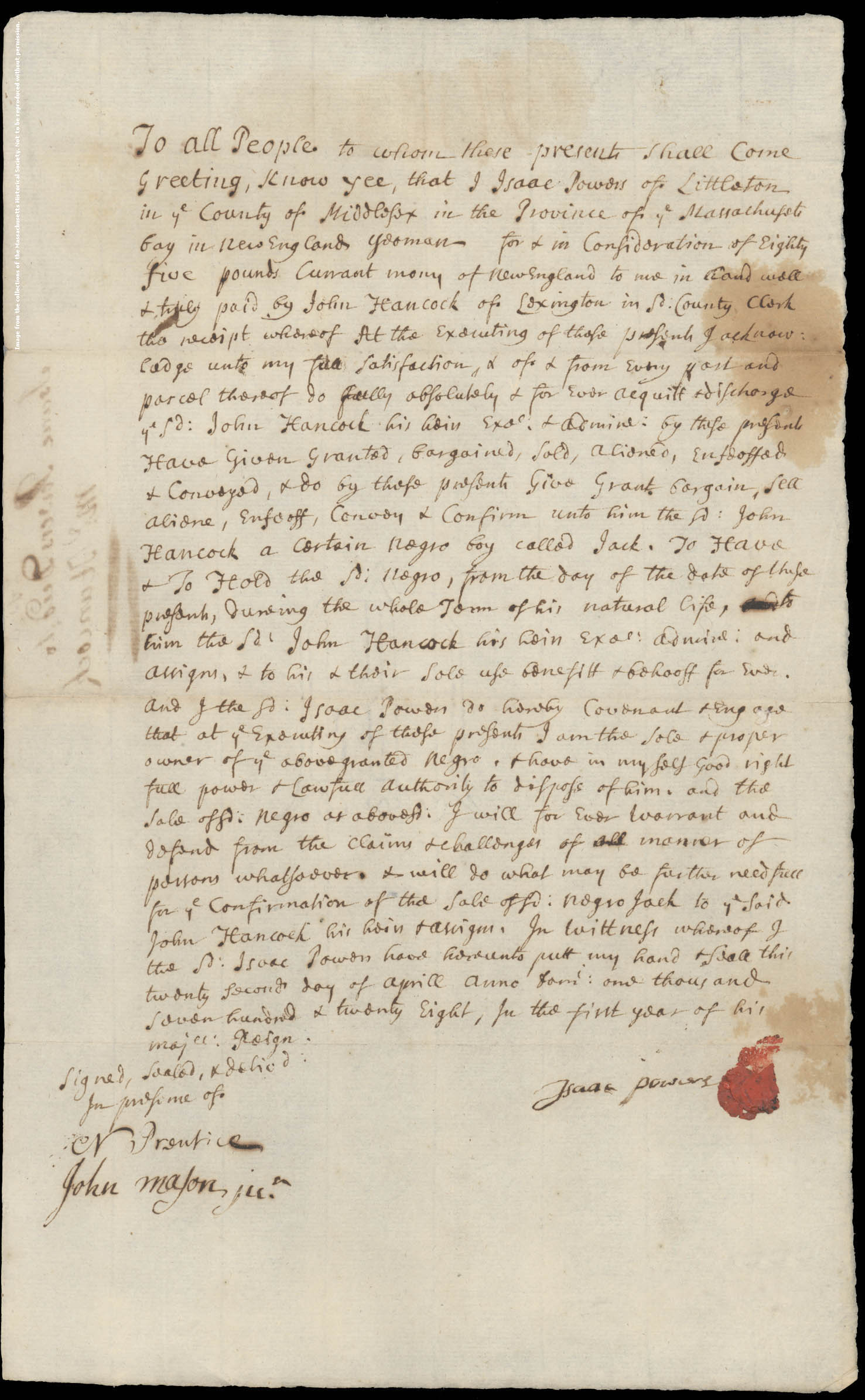

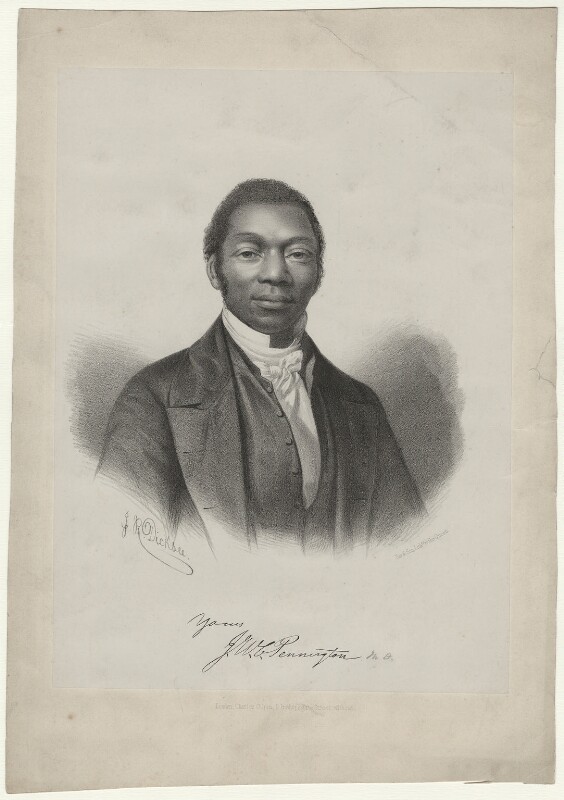

Mid-Maryland landowners with larger, more diversified farms often included an enslaved labor force of five or more adult men and women, keeping them occupied throughout the year with a variety of tasks. Frisby Tilghman’s Rockland Plantation in Washington County was a wheat farm comprised of more than a thousand acres. In 1820, Tilghman’s enslaved labor force of 29 men, women, and children included two “engaged in manufactures,” according to the US Census. James Pembroke (later Pennington) was trained first as a mason and then as a blacksmith while his brother was trained to masonry, skills that would keep them busy outside of the planting and harvest seasons. During the harvest, when labor needs expanded greatly for a short period of time, mid-Maryland farmers hired both free Black and white day laborers.

John Blackford’s journal of the daily workings on his Ferry Hill Plantation west of Sharpsburg, written in the 1830s, recorded the wide variety of jobs that occupied his large number of enslaved workers throughout the year. Blackford regularly employed two of his bondsmen as ferrymen on his commercial Potomac River ferry crossing. Blackford also operated a busy cordwood and shingle cutting business, which occupied several enslaved men as well as white day laborers year around. Sheep shearing, general maintenance, and errands were also jobs performed by Blackford’s enslaved people. During the July wheat harvest of 1838, he reported hiring at least three laborers, Nelson, Charles, and Nicholas Voluntine, in addition to his five enslaved men at work in the fields.

James W.C. Pennington, who escaped his enslavement on the Rockland Plantation of Frisby Tilghman in 1828, wrote twenty years later about his experience with Maryland slavery. Pennington rejected the popular idea that Maryland slavery was “the mildest from of slavery.” “The being of slavery, its soul and body, lives and moves in the chattel principle, the property principle, the bill of sale principle;” adding, “the cart-whip, starvation, and nakedness are its inevitable consequences to a greater or lesser extent, warring with the dispositions of men.” By example, he described Tilghman: “his prevailing temper was kind…and as respects discipline, a thorough slaveholder. He would not tolerate a look or a word from a slave like insubordination. He would suppress it at once, and at any risk. When he thought it necessary to secure unqualified obedience, he would strike a slave with any weapon, flog him on the bare back, and sell.”

Similarly, though John Blackford apparently gave his enslaved ferrymen Ned and Jupe (Julious) a surprising amount of independence, nonetheless, the people bound as Blackford’s laboring “property” did resist their condition. Daphney reportedly poisoned herself to induce a miscarriage of her twin babies, who would have been born enslaved-for-life, and twice attempted to escape her bondage. Blackford also reported using corporal punishment in 1838, giving “a few lashes” to Enouch [sic], wiping Isaiah, and later noting that he “punished Isaiah pretty severely.”

The sale of enslaved “property” often divided families, many permanently, though some like Jared Franklin found a way to unite. Jared Franklin, born enslaved on the Carroll County farm of J. Ross Key, the father of Francis Scott Key, described in his own narrative the loss of his family by sales. Jared had married Ann, enslaved by Adam Good of Taneytown, Maryland. When Francis Scott Key married and moved to Georgetown, he took Jared with him. After two years of separation, Key sold Jared to Adam Good. Reunited on the Good farm, Jared and Ann Franklin had two children, Henry and Harriet. But when Good became insolvent about 1813, “his property was disposed of,” resulting in the breakup of the Franklin family. Jared was sold to Joseph Engle of Little Pipe Creek; Ann and Harriet were sold to Philip Wampler; and Henry was purchased by Abraham Shriner of Little Pipe Creek. Years later, Jared, Ann, and Harriet were emancipated, and Henry escaped his bonds in 1837 and settled in Quakertown, Pennsylvania, where the family eventually reunited.

By 1850, mid-Maryland’s trend away from enslaved labor was evident in the census record. Only about 6.4% of Washington County’s population was enslaved, and 6% was “free colored.” In Frederick County, of the 41,000 people living in the county, 3,900 were enslaved and 3,800 were “free colored.” And in Carroll County, occupied by just over 20,000 individuals, 375 were enslaved African Americans and 374 were free people of color. By 1860, the Maryland counties of Carroll, Frederick, and Washington included a population of nearly 8,000 free African Americans, while just over 5,400 men, women, and children remained enslaved.

Freedom on the Border

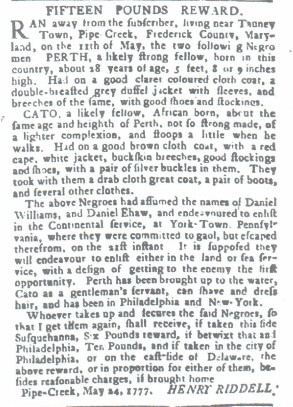

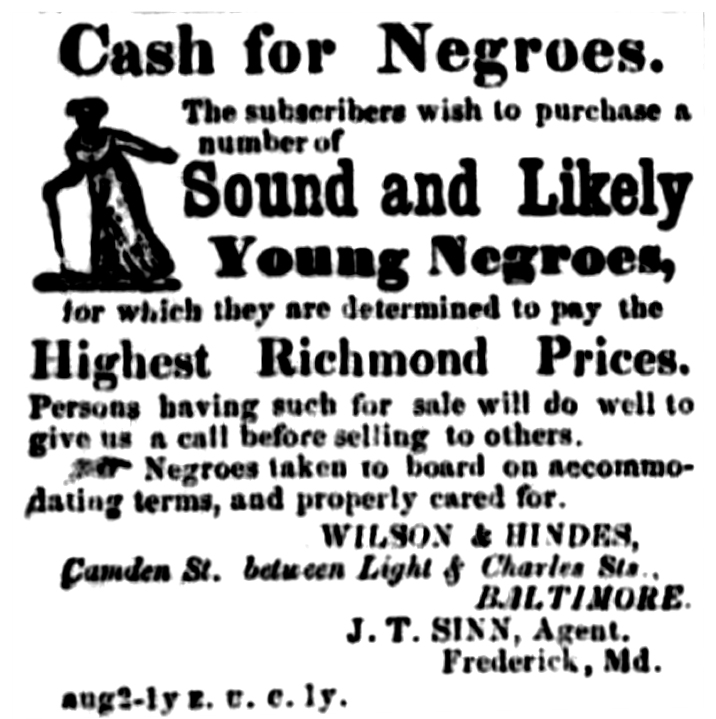

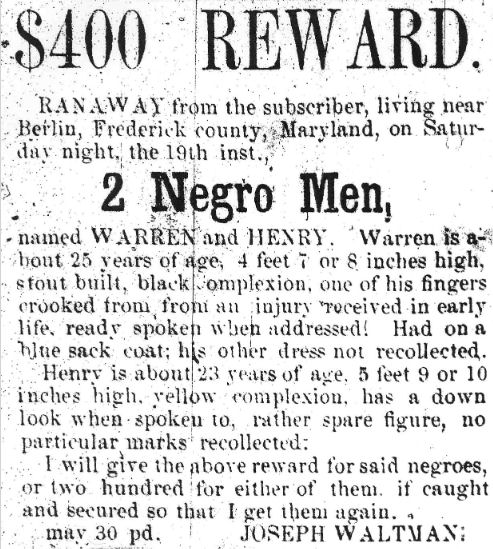

Self-liberation from bondage was as old as the institution of slavery. Among the freedom seekers from Frederick County, the earliest advertised was found in the Maryland Gazette in July 1775. She was an enslaved woman named Rhoad or Nancy Banneker, who left the farm of her enslaver (Abidnigo Hyatt) in the company of a fugitive Irish indentured servant. In 1777, two enslaved men named Perth and Cato liberated themselves from the farm of Henry Riddell near Taneytown (today’s Carroll County). Both men reportedly joined the Continental Army under new names – Daniel Williams and Daniel Ehaw. Beginning as early as 1780, several enslaved men liberated themselves from the Johnson & Co. Catoctin Furnace. A relatively well-dressed enslaved man named Phil enacted his own emancipation in January 1780. James Johnson posted a reward of $100 for his return.

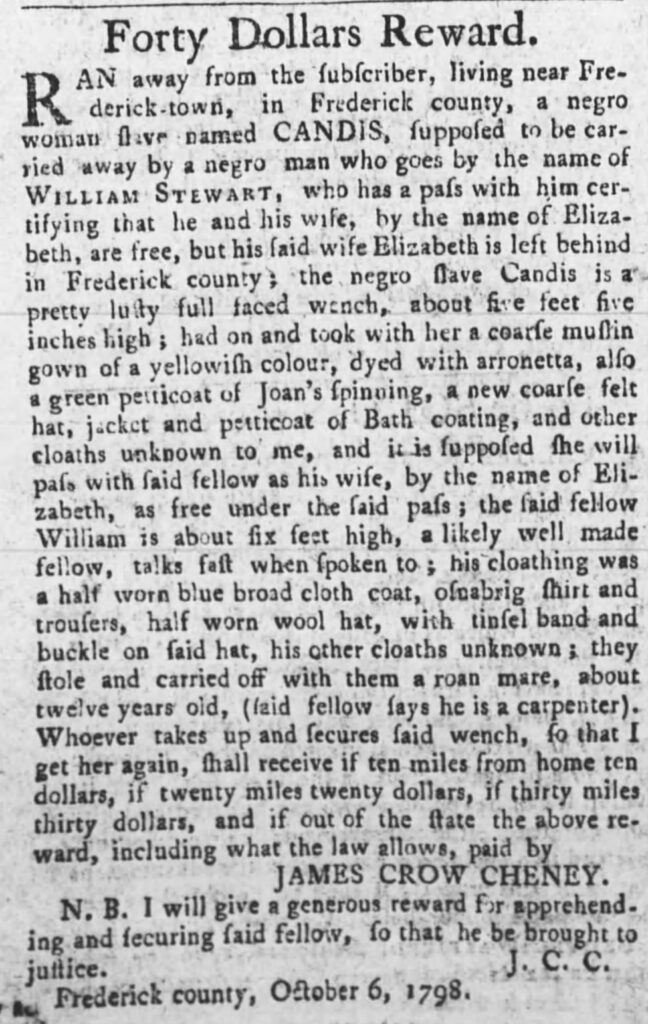

The routes followed by freedom seekers, shared by word-of-mouth and aided by people along the way, later known as the Underground Railroad (UGRR), was in operation throughout the mid-Atlantic region from as early as the 1780s. George Washington related in a letter to Robert Morris that Quakers in the Philadelphia area aided in the escape of an enslaved person from Alexandria, Virginia. In 1798, William Stewart, a free Black man, facilitated the liberation of Candis, an enslaved Black woman on the northern Frederick County farm of James Crow Chaney. Chaney’s “ran away” advertisement in the Maryland Gazette stated, “it is supposed she [Candis] will pass with said fellow as his wife, by the name of Elizabeth, as free under the said pass.” James W.C. Pennington rejected his bondage on the Washington County farm of his enslaver Frisby Tilghman in 1828. Following an arduous path with the help of many along the way, including Quakers in Pennsylvania, he made his way to New York where he was educated and became an articulate advocate for the abolition of slavery. By the 1850s the UGRR had developed into a complex network of “stations” leading to destinations in Pennsylvania, Ohio, New England, and Canada. There were agents in Maryland, both Black and white, Harriet Tubman perhaps the most well-known of the Maryland UGRR agents. In Washington County, two white brick makers from Hagerstown, George Stimitz and Frederick Shriver, were accused of being agents of the UGRR and inducing an enslaved worker from Loudoun County, Virginia to “run off” in 1858. There were numerous others who offered their aid, many whose names will never be known.

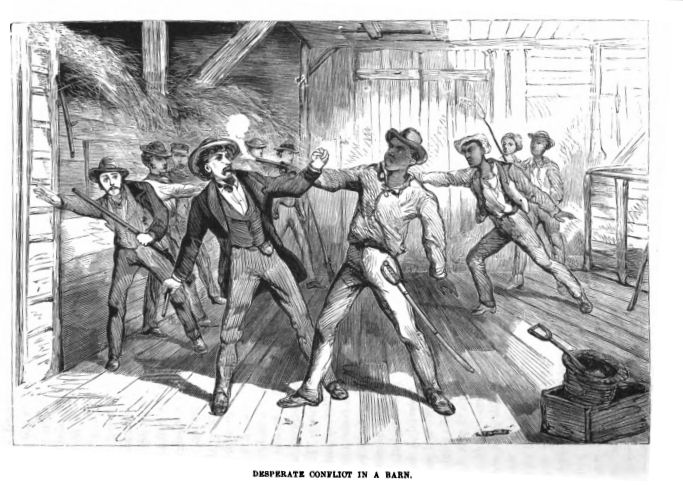

For fugitives running from Virginia’s lower Shenandoah Valley or from Maryland locations, the flight to Pennsylvania was relatively short. James Pennington’s journey to freedom in 1828 was fairly typical – he walked established roads by night following the North Star – but also fraught with peril. Pennington’s journey to freedom was much longer than necessary because the nights were cloudy and he was often unable to follow the North Star. Instead of going north, Pennington mistakenly walked east, toward Baltimore. Like other fugitives, Pennington had to be wary of slave hunters and was even caught once by locals in Baltimore County. With luck on his side, Pennington found his way to Pennsylvania and stumbled onto the farm of an UGRR agent. In 1853, Wesley Harris (alias Robert Jackson), enslaved in Virginia had a similar experience. Escaping from Harpers Ferry with several companions, Harris was captured in a barn near “Terrytown, Md.” [Taneytown] in Carroll County. Although severely injured, Harris escaped with the help of sympathetic Black servants in the tavern where he was recuperating. He made his way to Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, and freedom, but his comrades were taken to jail in Westminster, Maryland.

Beginning in 1841 Gettysburg was host of the Slave’s Refuge Society, established by five members of the St. Paul’s African Methodist Episcopal (AME) Church. The founders stated their intention declaring: “We feel it our indispensable duty to assist such of our brethren as shall come among us for the purpose of liberating themselves, and to raise all the means in our power to effect our object, which is to give liberty to our brethren groaning under the tyrannical yoke of oppression.” In 1858, Basil Biggs, a free African American from Carroll County, Maryland, moved to Gettysburg and opened his home to fugitives, leading them to Quaker Valley under cover of night where they continued their journey north.

During the decade leading up to the Civil War, new state and federal laws made the avenues to freedom much harder to navigate. With the passage of the federal Fugitive Slave Act in 1850, many freedom seekers from Maryland and Virginia were not as lucky as Pennington and Harris. Moses Horner, who left his enslavement in Jefferson County, Virginia (now West Virginia), was working near Harrisburg, Pennsylvania in 1860 when he was arrested as a fugitive slave. Horner was tried in federal court, found guilty, and “remanded to the custody of his owner,” Charles T. Butler. Others never made it as far as Pennsylvania, caught by locals or slave hunters and held in various Maryland county jails. In June 1856, John Bacon, enslaved by Wilkens Glenn of Baltimore, escaped his employer near Sykesville in Howard County but was caught and jailed in Carroll County. Sheriff Joseph Shaeffer described young Bacon as having “an honest and interesting appearance.” In 1859, Carroll County Sheriff William Wilson advertised the capture of freedom seeker William Adams.

In Maryland, manumission had become a common path to freedom, particularly in Carroll, Frederick, and Washington Counties. For some enslavers perhaps it was a way to clear the conscience, for others a way to relieve oneself of unprofitable labor. Many saw the looming demise of the institution of slavery by 1860. One local newspaper observed that year: “There were fifty slaves manumitted in Washington County previous to the first of June, the period when the new law on that subject went into operation.” The “new law” referenced was a new state law prohibiting manumissions beginning in June 1860. It was an attempt by the state legislature to stem the growth of the free Black population in Maryland. With the loss of manumission as a pathway to freedom, the stream of freedom seekers became a “stampede” in 1860, according to one Frederick County newspaper, “It has been suggested that the approach of the first of June, on which day the law forbidding manumissions will go into effect, was the cause of their departure.”

James W.C. Pennington spoke for his enslaved brethren when he asked for “justice, truth, and honor as other men do.” At the time when he wrote those words, in 1849, freedom for the enslaved African Americans throughout the United States was still more than a decade away. It would take a Civil War to create the environment necessary to push politicians to abolish slavery, even if not for “justice, truth, and honor.” Literally sandwiched between Virginia to the south and Pennsylvania to the north, the state of Maryland was politically and economically divided, a microcosm of the country’s sectional divide over slavery. In October 1860, the editor of the Hagerstown newspaper Herald & Torch noted with remarkable insight the impending devastation the Civil War would bring:

Washington county is a border county, and the people of no State and no county have suffered more from the accursed agitation of slavery than they, and none would share larger in the horrors of a dissolution of the Government.

In September 1862, the town of Sharpsburg, located on the Antietam Creek in Washington County, stood at the center of a battle that would alter the war and the slavery debate. The outcome of the Battle of Antietam precipitated President Abraham Lincoln’s issuance of the Emancipation Proclamation, freeing the enslaved people in the rebelling states. Ironically, although the battle took place on Maryland ground, those enslaved in Maryland, a state still within the Union, would continue to live in bondage for two more years. But the politics and circumstances of the Civil War would bring closer the long hoped-for freedom.