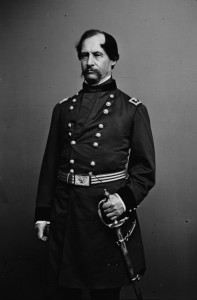

On August 3, 1864, Major General David Hunter, head of the Department of West Virginia (which included western Maryland), complained in a letter to Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton that it is “impossible … to conduct military operations advantageously in this department if … spies and traitors  are permitted to go at large and continue their disloyal practices in the midst of my army.” The “spies and traitors” to which Hunter referred were those Southern sympathizers who had, allegedly, given aid to General Jubal Early’s Confederate troops during their recent raid into the area, and who had directed Confederate troops to the houses of Union men which they might plunder. Hunter’s complaint tapped into the bitterly polarized sectionalism in the area that, after three years of war and Early’s raids in the region, had deepened the hostility of Unionists towards Confederate sympathizers. Demands for retaliatory action came from newspapers like the Frederick Examiner, which declared that Unionists and “domestic traitors” could “no longer exist in this State,” and that the latter should be “expelled from our midst.”

are permitted to go at large and continue their disloyal practices in the midst of my army.” The “spies and traitors” to which Hunter referred were those Southern sympathizers who had, allegedly, given aid to General Jubal Early’s Confederate troops during their recent raid into the area, and who had directed Confederate troops to the houses of Union men which they might plunder. Hunter’s complaint tapped into the bitterly polarized sectionalism in the area that, after three years of war and Early’s raids in the region, had deepened the hostility of Unionists towards Confederate sympathizers. Demands for retaliatory action came from newspapers like the Frederick Examiner, which declared that Unionists and “domestic traitors” could “no longer exist in this State,” and that the latter should be “expelled from our midst.”

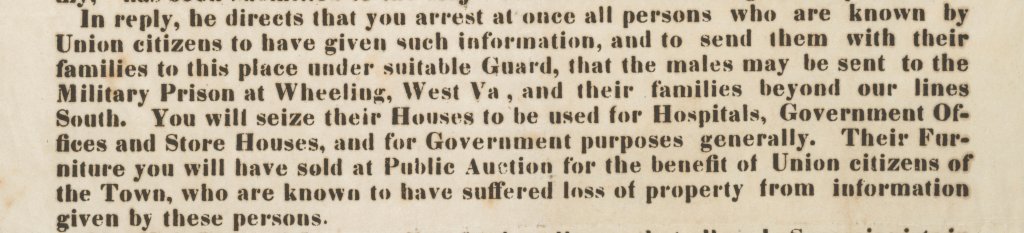

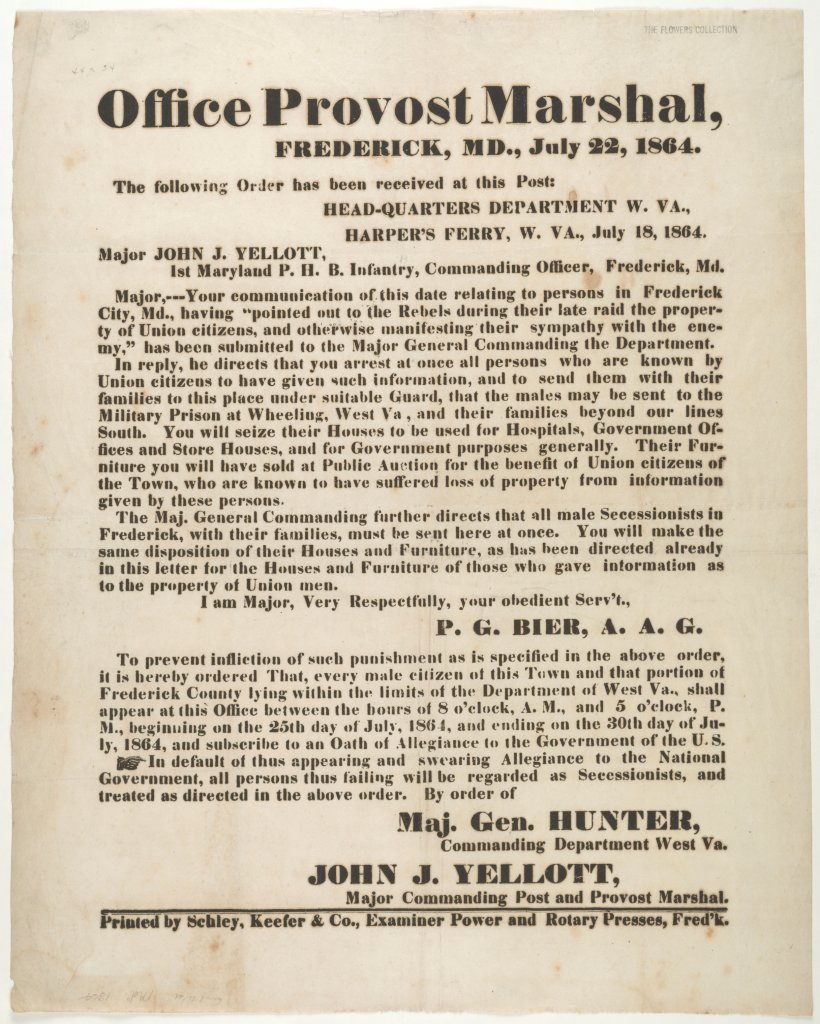

General Hunter’s outrage, and the sentiment expressed in the Frederick Examiner, found their way into an order Hunter issued on July 18, 1864. Hunter commanded that all those who had directed Confederate soldiers to the property of Union men be identified and arrested. Men were to be imprisoned in Wheeling, and their families deported somewhere beyond federal lines. Their houses were to be seized to be used for “government purposes,” while their furniture was to be sold at auction to benefit the citizens who lost property during the Confederate raid.

Charged with carrying out this order was Major John I. Yellot, the Provost Marshal of Frederick. Yellot requested a list of all individuals who “had pointed out the Residences and Properties of Union men to the Rebels, during their late raid through the State,” or had in some way given them “aid and encouragement.” Yellot reduced the severity of Hunter’s order by announcing that all Frederick men who reported to his office between July 25 and July 30 and “subscribe[d] to an Oath of Allegiance to the Government of the U.S.” would be spared deportation; those who refused the oath were to be “regarded as Secessionists” and deported.

On August 1, 1864, Hunter issued a new order which put even more pressure on Southern sympathizers in Frederick. His Special Order No. 141 created a list of Frederick residents who were already determined eligible for deportation because of their anti-Union views. By August 1864, a citizen of Frederick could be deported to the South for not only assisting the Confederates with their looting but also for expressing opinions supporting the Confederacy.

In accordance with General Hunter’s orders, John W. Baughman, the owner and editor of the Republican Citizen, and his associate, James Norris, were directed to leave Frederick. The Republican Citizen was an overtly secessionist newspaper, and this was not the first time that the paper’s views had attracted attention from Union authorities. In 1862, Baughman was arrested by the Federal government for “disloyal conduct,” although he was released shortly thereafter. In 1863, the Republican Citizen was suspended from mail service for continuing to assert sympathy for the South. Now in the summer of 1864, it was more risky than ever for Baughman to espouse his secessionist views from so public a platform.

Republican Citizen, and his associate, James Norris, were directed to leave Frederick. The Republican Citizen was an overtly secessionist newspaper, and this was not the first time that the paper’s views had attracted attention from Union authorities. In 1862, Baughman was arrested by the Federal government for “disloyal conduct,” although he was released shortly thereafter. In 1863, the Republican Citizen was suspended from mail service for continuing to assert sympathy for the South. Now in the summer of 1864, it was more risky than ever for Baughman to espouse his secessionist views from so public a platform.

Baughman continued, however, and ran afoul of General Hunter’s order. His paper was suppressed, his property confiscated, and he and his family were ordered to go beyond federal lines. His wife and children went to Clark County, Virginia, to live with the Dearmont family. One son served in the Confederate Army. Baughman himself went to Richmond and began working for his friend, General JohnC. Breckinridge, the Confederate Secretary of War. Baughman remained there for the duration of the war.

Baughman’s partner was also ordered to go South, but James Norris fared differently once in Virginia. The Frederick Examiner reported that the Confederates did not want Norris: “the Rebels will not receive him.” Norris headed back north, met with the provost marshal at Harpers Ferry, was released from his deportation, and returned to Frederick. The banishment of his wife and family had been postponed due to his wife’s illness; Norris’ return meant that the family was reunited within a week. Norris thus escaped the full extent of the deportation sentence.

The deportation of John Baughman and his family seemed entirely appropriate to many in the region who supported the Union cause and who had become embittered towards those in their midst who  supported the Confederacy. Others felt differently. They were alarmed at what they perceived to be extreme measures instituted by General Hunter. Former Governor Francis Thomas, in an August 13, 1864 letter to Postmaster General Montgomery Blair, called Special Order No. 141 “madness and folly,” and expressed “surprise at the whole proceeding” when thinking of the “misery which would be brought upon women and children” not guilty of criminal acts. Another letter from Lieutenant Colonel George Dennis, of the 1st Maryland Regiment, Potomac Home Brigade, respectfully requested that President Lincoln “interpose his authority, and … have [Hunter’s] order revoked” on the grounds that it was “destructive to our interest as a community and of no practical benefit to the Government.” A similar letter from a relative of one of the men on the arrest list reached Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton on August 2; Stanton forwarded that letter to President Abraham Lincoln.

supported the Confederacy. Others felt differently. They were alarmed at what they perceived to be extreme measures instituted by General Hunter. Former Governor Francis Thomas, in an August 13, 1864 letter to Postmaster General Montgomery Blair, called Special Order No. 141 “madness and folly,” and expressed “surprise at the whole proceeding” when thinking of the “misery which would be brought upon women and children” not guilty of criminal acts. Another letter from Lieutenant Colonel George Dennis, of the 1st Maryland Regiment, Potomac Home Brigade, respectfully requested that President Lincoln “interpose his authority, and … have [Hunter’s] order revoked” on the grounds that it was “destructive to our interest as a community and of no practical benefit to the Government.” A similar letter from a relative of one of the men on the arrest list reached Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton on August 2; Stanton forwarded that letter to President Abraham Lincoln.

Lincoln’s response on August 3, 1862 was to direct the Secretary of War to immediately suspend the order of General Hunter. Lincoln also directed Hunter to “send … a brief report of what is known against” each of the southern-sympathizing suspects. As a result of President Lincoln’s directive, General Hunter concluded on August 7 that it was “impossible to conduct the affairs of any Department successfully,” and requested to be relieved of his command. On August 29, 1864, this request was granted.

John Baughman and his family would return to Frederick after the war, in late April 1865. He resumed publication of the Republican Citizen, which now reflected the position of the Democratic Party. Baughman died in 1872.

Baughman and Norris were the only Southern sympathizers from Frederick deported to the South under Order 141. Despite the animosities that existed in the border region after more than three years of war, widespread deportations did not occur. Efforts toward that end were made, but were held in check by the federal government. In this case, General Hunter was found to be overzealous, and his order was countermanded by the commander in chief.