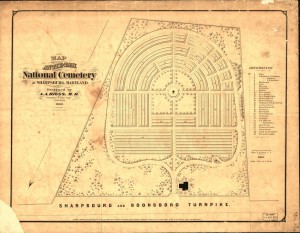

A map of Antietam National Cemetery from 1867 includes in the bottom right a teardrop shaped piece  of ground dominated by a sizeable boulder. A.A. Biggs, the man responsible for the design of the cemetery, deliberately diverted the path so as to enclose the rock, indicative of his recognition that there was tangible interest in the rock. Lee’s Rock, as the outcropping came to be known, was also included in Antietam National Cemetery as part of a survey later that year meant to portray the Confederate lines during the Battle of Antietam. However, by 1897 the rock was no longer present in depictions of the cemetery. The story of Lee’s Rock’s inclusion at the cemetery and its subsequent demolition is representative of the larger challenge facing a postbellum United States tasked with reuniting not only its previously warring citizenry, but also honoring the legacy of both the victors and the vanquished

of ground dominated by a sizeable boulder. A.A. Biggs, the man responsible for the design of the cemetery, deliberately diverted the path so as to enclose the rock, indicative of his recognition that there was tangible interest in the rock. Lee’s Rock, as the outcropping came to be known, was also included in Antietam National Cemetery as part of a survey later that year meant to portray the Confederate lines during the Battle of Antietam. However, by 1897 the rock was no longer present in depictions of the cemetery. The story of Lee’s Rock’s inclusion at the cemetery and its subsequent demolition is representative of the larger challenge facing a postbellum United States tasked with reuniting not only its previously warring citizenry, but also honoring the legacy of both the victors and the vanquished

Lee’s Rock gained its name from locals who believed that Confederate General Robert E. Lee had stood upon the boulder to gain a better view of the battlefield during the Battle of Antietam on September 17,  1862. The object was popular to tourists visiting the battlefield, who often stood on the rock as they believed Lee had done. Of more concern to the Board of Trustees of the Antietam National Cemetery were those visitors who broke off pieces to carry away as souvenirs of the battle or, especially troubling to trustees from Northern states, as a relic from the renowned commander. For these board members, the presence of a Southern monument on ground made hallow by the sacrifices of Union soldiers was entirely unacceptable: they believed the cemetery’s sacred space had to be purified of this Southern taint.

1862. The object was popular to tourists visiting the battlefield, who often stood on the rock as they believed Lee had done. Of more concern to the Board of Trustees of the Antietam National Cemetery were those visitors who broke off pieces to carry away as souvenirs of the battle or, especially troubling to trustees from Northern states, as a relic from the renowned commander. For these board members, the presence of a Southern monument on ground made hallow by the sacrifices of Union soldiers was entirely unacceptable: they believed the cemetery’s sacred space had to be purified of this Southern taint.

In March 1866, the New York Times reported that there was a “difference of opinion” among the trustees about the future of Lee’s Rock. Two months later, the trustees decreed that the rock should be demolished, amid concerns that the rock’s continued presence on the cemetery grounds was “tantamount to erecting a monument to General Lee.” The rock received a respite from the sledgehammer when the trustees backed away from their decision and instead settled on leaving the boulder intact as a “feature of historic interest.”

Rather than view this failed plot to remove the stone as a victory for General Lee’s legacy, the Columbus Daily Sun hailed the decision as a “sensible determination,” because the board of trustees had refused to martyr Lee’s Rock and thereby create a perpetual “moral monument to Lee.” This enthusiasm for the board’s act of clemency, however, was not shared by all of the cemetery’s trustees.

On June 17, 1868 a measure was passed by the Board to remove “all fixed rocks from the cemetery grounds which project above the surface at least one foot.” As the only outcropping in the cemetery that met this criterion, Lee’s Rock was clearly the intended target of this new ordinance. The circumstances around this vote suggest that sentiment for the removal of the rock was not widely held among the Board of Trustees. The group of trustees that passed this resolution was barely sufficient to form the quorum necessary for the vote. New members of the board had been appointed by the governor of Maryland, many of whom had Southern sympathies, and there was likely less desire among the members of this new board to obliterate the rock than there had been during the first attempt in 1866. Yet when the measure passed, the impending destruction of Lee’s Rock did not inspire a new round of controversy. The rock was quietly removed. The Hagerstown Mail claimed that as late as September 1868 few people were even aware of the rock’s removal. Instead, the new source of controversy at the cemetery was Maryland’s insistence that Confederates killed at the battle be interred at, or adjacent to, the Union soldiers’ burial ground.

Seemingly irrelevant to the politicking around Lee’s Rock was its veracity as a historical object.  Interestingly, Northerners adamant about the need to remove the boulder were more apt to treat the rock as if General Lee had actually stood upon it because it therefore represented “a southern pollution needing to be removed from the landscape.” In contrast, Confederate officers who visited the battlefield often rejected the notion that the general did stand upon the outcropping. The most prominent repudiation of Lee’s Rock’s authenticity was issued by Henry Kyd Douglas, a resident of Maryland who served on Confederate General Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson’s staff. According to Douglas, the rock was enclosed by a clump of trees on what would later become Cemetery Hill during the Battle of Antietam. Therefore, he wrote that General Lee never even saw the rock that bore his name, let alone stood on it; even if he had been able to stand upon it, Douglas contended that the only view it would have afforded would have been that of the surrounding trees.

Interestingly, Northerners adamant about the need to remove the boulder were more apt to treat the rock as if General Lee had actually stood upon it because it therefore represented “a southern pollution needing to be removed from the landscape.” In contrast, Confederate officers who visited the battlefield often rejected the notion that the general did stand upon the outcropping. The most prominent repudiation of Lee’s Rock’s authenticity was issued by Henry Kyd Douglas, a resident of Maryland who served on Confederate General Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson’s staff. According to Douglas, the rock was enclosed by a clump of trees on what would later become Cemetery Hill during the Battle of Antietam. Therefore, he wrote that General Lee never even saw the rock that bore his name, let alone stood on it; even if he had been able to stand upon it, Douglas contended that the only view it would have afforded would have been that of the surrounding trees.

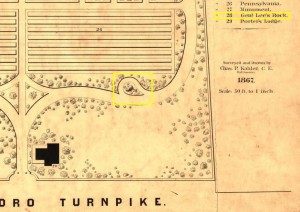

On September 17, 1867 the dedication ceremony held at Antietam National Cemetery was attended by  “loyal men and women,” governors from Northern states, Union generals, and President Andrew Johnson. Conspicuously absent among the soldiers buried there and among the crowd gathered were supporters of the Confederacy. Also soon to be missing was Lee’s Rock, an association with the Confederacy deemed unacceptable at a site dedicated to slain Union soldiers. The rock was destined for obliteration, sacrificed in this post-war effort to honor only some of those soldiers who had so recently struggled in the battle along Antietam Creek.

“loyal men and women,” governors from Northern states, Union generals, and President Andrew Johnson. Conspicuously absent among the soldiers buried there and among the crowd gathered were supporters of the Confederacy. Also soon to be missing was Lee’s Rock, an association with the Confederacy deemed unacceptable at a site dedicated to slain Union soldiers. The rock was destined for obliteration, sacrificed in this post-war effort to honor only some of those soldiers who had so recently struggled in the battle along Antietam Creek.