Women and children participated in the Civil War in a variety of capacities, not just as spectators or victims, but as real actors who contributed both on the home front and in the armies. They were affected by the war, and they had an effect on it.

Women and children participated in the Civil War in a variety of capacities, not just as spectators or victims, but as real actors who contributed both on the home front and in the armies. They were affected by the war, and they had an effect on it.

Children on the border grew up in divided families in divided communities, witnessing the intense debates of the adults. On the mid-Maryland border, the Civil War came right to their neighborhoods, and children learned what it meant to have an army descend on their farms and villages. It meant seeing soldiers in their stores, in their churches, and camped in their fields. It meant watching ambulances with wounded soldiers going through their streets. It meant working alongside their mothers, sisters, and aunts to help those wounded soldiers in make-shift hospitals, which might be their schools, and sometimes their homes. It meant seeing their families’ resources commandeered, and living with constant scarcities of food and goods. Most importantly, it meant separation from fathers and brothers, and, for some, it meant learning how to mourn. On the border, many childhoods were truncated because of the Civil War.

For women, the Civil War provided an opportunity for some to step out of nineteenth century gender roles, although the war did not provoke any major redefinition of women’s sphere. Women were still unable to hold office or vote, and were thus outside the political process in those capacities. Yet during the Civil War, they participated politically by attending rallies, joining Ladies’ Aid Societies, circulating petitions, and organizing fund-raising campaigns. They ran farms and businesses. They were witnesses, writers, soldiers, smugglers, nurses, cooks, laundresses, prostitutes, and mourners. Women on the border were deeply involved in this conflict.

The experience of African American women and children on the border differed from that of white women and children, as the stakes were different. When Confederate armies came through the border region, black women and children, as well as black men, had not only their safety and their property but their freedom on the line. Theirs was a battle of another kind.

Children on the Border

Adult debates over slavery, secession, and war filtered down to their children, who became politicized at very young ages. Children on the border had to sort out where their allegiances should reside in the confused and inflamed political landscape that divid ed their neighbors and sometimes even their families in this border region. Once they were aligned with a side, children expressed their loyalty in small but significant ways. In September 1862, as Stonewall Jackson’s troops made their way through Middletown, “two very pretty girls” appeared, boldly waving Union flags at the Confederate troops. Jackson is reported to have “bowed and lifted his cap and with a quiet smile said to his staff, ‘We evidently have no friends in this town.’” This type of defiant partisan behavior from children occurred on other occasions. A young boy in Hagerstown, encountering Confederate troops on their way to Gettysburg, similarly stood on a corner and waved Union flags at them. Even the youngest members of society had become politicized.

ed their neighbors and sometimes even their families in this border region. Once they were aligned with a side, children expressed their loyalty in small but significant ways. In September 1862, as Stonewall Jackson’s troops made their way through Middletown, “two very pretty girls” appeared, boldly waving Union flags at the Confederate troops. Jackson is reported to have “bowed and lifted his cap and with a quiet smile said to his staff, ‘We evidently have no friends in this town.’” This type of defiant partisan behavior from children occurred on other occasions. A young boy in Hagerstown, encountering Confederate troops on their way to Gettysburg, similarly stood on a corner and waved Union flags at them. Even the youngest members of society had become politicized.

The diary of thirteen-year old Margaret Mehring, who attended a boarding school in New Windsor, offers another glimpse of a child’s view of the war. When she learned that the Confederate troops marching towards Gettysburg in July 1863 engaged in horse theft, Margaret wrote that stealing horses was “a piece of art which they [the Confederates] appear to be very near perfect in and one that I think is a pretty occupation for the much bosted Souther Chivelry [sic] to be engaged in but then I suppose that they entertain the very good idea that exercise is necessary to health.” Perhaps her sense of humor masked her fears. She continued, hoping that the “Rebels” “will meet a warm reception from Pensylvania [sic] in the shape of balls for taking the trouble and liberty of calling on them without an invitation.” The acerbic wit Margaret used on the Confederate troops was exchanged for glowing praise when she wrote about the Union army:

“They were dressed very nicely and rode handsome horses,” she gushed, “and said they never felt happier than when they set foot on Maryland soil.” And with the arrival of the Union troops, rumors that Confederate soldiers were nearby no longer worried Margaret: they “almost ceased to cause an extr pulsation [sic] of the heart.”

While Margaret Mehring was commenting on the arrival of the Confederate troops, thirteen year old William Bayly of Gettysburg was trying to outrun the advancing Confederates who would surely confiscate his horse, Nellie. William and Nellie raced away from their Confederate pursuers, riding for almost thirty miles until they were in a safe spot. At thirteen years of age, concealing the horses was a way William could contribute. He was too young to join the army, and would be left at home with the women during the battle. William saw his role in terms of the gender proscriptions of the day, as he would later write: “I, being the oldest responsible male member of our family at home, must see that the horses are concealed, the cows driven to shelter, and the feminine portion of the family protected. All of which, of course, I saw to at once. But the question was, how could I look after a number of hysterical women.” Even as a young teenager, William Bayly had adopted society’s image of women as fearful and requiring the protection of a man.

Children were often thrust into roles that brought them in direct contact with the impact of the fighting. Some became helpers in the care of the wounded. Nine-year old Sadie Bushman was awoken in the early morning hours of July 1, 1863 and told to flee with her brother to the safety of her grandparent’s farm. The two-mile journey was almost brought to a sudden and violent end when a shell exploded near the children. A Union officer witnessed the narrow escape, and helped them the rest of

Children were often thrust into roles that brought them in direct contact with the impact of the fighting. Some became helpers in the care of the wounded. Nine-year old Sadie Bushman was awoken in the early morning hours of July 1, 1863 and told to flee with her brother to the safety of her grandparent’s farm. The two-mile journey was almost brought to a sudden and violent end when a shell exploded near the children. A Union officer witnessed the narrow escape, and helped them the rest of  the way to the refuge of the farm. But at the farm, “things were almost as bad.” The grandparent’s house had been turned into a hospital, with an operating tent set up in the yard. A surgeon needed help with a man whose leg was shattered, and years later, Sadie recalled: “He turned to me and asked me if I could hold a cup of water to the poor man’s mouth while the leg was being taken off.” Sadie reported being “terribly frightened,” but complying, and then remaining for “the most fearful two weeks I ever knew,” helping with the wounded soldiers. She became known as the “little nurse of Gettysburg.”

the way to the refuge of the farm. But at the farm, “things were almost as bad.” The grandparent’s house had been turned into a hospital, with an operating tent set up in the yard. A surgeon needed help with a man whose leg was shattered, and years later, Sadie recalled: “He turned to me and asked me if I could hold a cup of water to the poor man’s mouth while the leg was being taken off.” Sadie reported being “terribly frightened,” but complying, and then remaining for “the most fearful two weeks I ever knew,” helping with the wounded soldiers. She became known as the “little nurse of Gettysburg.”

Occasionally children were in the position of witnessing the battles themselves as they raged around their homes and farms. In July 1864, during the Battle of Monocacy, six- year old Glenn Worthington watched the Confederate artillery deploy in his front yard as he peeked through the cracks in the boards covering the cellar windows of his home. Confederate cannon were fired from the Worthington front yard, and as the battle got closer to the Worthington house, Glenn could see “the blue pants of the pursuing Yankees,” and could hear “the noise of the clamor and straining of men in mortal combat.” After the fighting ended, Glenn and his seven year old brother Harry were sent by their father to the Worthington’s wheat field to “get several sheaves of wheat, and to make a pallet of it” for a wounded soldier. The Battle of Monocacy remained a part of Glenn Worthington; as an adult he would write an account of the battle and work tirelessly to preserve the battlefield.

For African American children, war on the border brought extra dangers. Benjamin Tucker Tanner served as the minister of Quinn’s Chapel in Frederick during the latter half of the war, and his son, Henry Ossawa Tanner, later wrote about his memories of the family’s wartime experiences. “From our attic window the rebel camp and soldiers could be seen. Once my father for some cause was at the [church] and by his clothes was recognized as a minister. ‘Hello!” [said a soldier to his father] “…what are you doing with those duds on, take this,’ and he was kicked out of the [church]. I believe my father said he was drunk.” Henry also remembered that his father took the precaution of nailing boards over the windows in the house to make it look abandoned, and although rebel soldiers passed by their house all day long, only one stopped to bang on the door, and he was told by an officer to move on.

For African American children, war on the border brought extra dangers. Benjamin Tucker Tanner served as the minister of Quinn’s Chapel in Frederick during the latter half of the war, and his son, Henry Ossawa Tanner, later wrote about his memories of the family’s wartime experiences. “From our attic window the rebel camp and soldiers could be seen. Once my father for some cause was at the [church] and by his clothes was recognized as a minister. ‘Hello!” [said a soldier to his father] “…what are you doing with those duds on, take this,’ and he was kicked out of the [church]. I believe my father said he was drunk.” Henry also remembered that his father took the precaution of nailing boards over the windows in the house to make it look abandoned, and although rebel soldiers passed by their house all day long, only one stopped to bang on the door, and he was told by an officer to move on.

Caring for the wounded, hiding horses, and having battles erupt in their midst affected children in another way – it displaced them from their schools. Schools near battlefields often became hospitals, and were forced to suspend classes for that reason. In Frederick, the entire fall semester of 1862 was lost after the Battle of Antietam when schools were used for the care of the wounded.

At St. James, an Episcopal high school in Hagerstown which attracted students from both the North and the South, it was the politics of the war, not the wounded, that impinged on academics. In an effort to dampen passions, the headmaster banned political discourse, both written and oral. It did not work. Students continued to express their positions, and, in one instance in April 1862, some walked out on a service held in accordance with President Lincoln’s call for a day of thanksgiving. And when Confederate cavalry passed through the grounds of the school on their way to Gettysburg, the reaction was more extreme: eight students left St. James to join the Confederate army. The tensions enveloping the school community created a rupture that the school could not endure, and St. James eventually closed in September 1864. It would not reopen until 1869.

The students at St. James who tried to enlist in the Confederate Army were not the only young people attempting to join one of the armies, or at least play at war. “Young America is full of the war spirit, and withal apt scholars,” observed Hagerstown’s Herald and Torch Light in September 1863. Enthusiasm among some young boys for playing “war-games” prompted the newspaper to issue a warning to parents about the dangers involved in “fighting sham battles … in which [the boys] throw stones and fire pistols at each other with a recklessness which … greatly imperils their own safety.”

These boys on the border have learned to form battle lines, tear down fences, throw up entrenchments, advance skirmishers, yell, curse, and swear, and go through the whole program of a real engagement with all the coolness and courage of old veterans; and of course they will not rest satisfied until they also have a full complement of killed and wounded, for the accommodation of which they have little wagons which they call “ambulances.” In one of these battles, which took place on Saturday last, a boy was shot and narrowly escaped death, and others will assuredly be hurt, if the parents or proper authorities do not intervene and close the war.

Other boys were not content with playing at war, and some found ways to join the Union or Confederate armies even though they were underage. Although both armies stipulated that recruits had to be at least eighteen years old, sometimes older-looking fifteen- and sixteen-year olds could get past the recruiting sergeants. One of these boys, fifteen-year old Edward McSherry of Frederick, was determined to enlist in the Confederate Army. He got his chance in July 1864. While visiting a family friend east of Frederick, McSherry found himself behind rebel lines during the Battle of Monocacy. Someone gave him a horse, and he joined Company D of the First Maryland Cavalry. He served with the regiment until it surrendered at Appomattox in April 1865. On June 29, 1865, at the age of sixteen, McSherry petitioned President Johnson for a pardon for his late actions, citing his “youth and inexperience” and promising to execute the “duties which good citizenship” demanded. The pardon was granted, and Edward McSherry apparently made good on his promise: he led a respectable life as a dentist and businessman in the city of Frederick until his death in 1900.

The Civil War had the effect of disrupting childhood in the mid-Maryland region. Children were politicized by their family’s attachment to the Union or to the Confederacy, and the anxiety produced by the hostilities that divided families and communities was profound for children. This, along with the violence and suffering they witnessed, left a permanent mark on them. Very few would emerge from the war unaffected by it.

Women Support the War

The battlefield was not the sphere in which a proper nineteenth century woman operated, but women could perform wartime work without going anywhere. Women could support the soldiers from their homes in ways that emanated from their true nature. They could sew flags, wave flags, wear flags, and also take on the domestic tasks of producing enormous quantities of food, clothing, bedding, and bandages, for the army. They could, it was expected, shift effortlessly from caring for their families to caring for the soldiers.

Women’s work was thus critical to the war effort. But what happened when the war came to their backyards? Women in the mid-Maryland region would find out, and while many would offer support consistent with their proper roles, some would step out of those proscribed positions.

As they watched their husbands and sons go off to join the Union or Confederate armies, women on the border took steps to support them in proper ways from home. In May 1861 the women of Clear Spring began wearing Union aprons: “The bib is studded with stars, the skirt streaked with stripes, and warm, true, brave hearts, beating under all.” A “Union pole” was raised in the spring of 1861 in Middletown to accommodate a flag sewn by the ladies of the town. The women of Westminster presented the local military company with a wreath and bouquets of flowers. Frequently, women of the region gave a hand-sewn flag to soldiers from other states to whom they had grown attached due to the soldiers’ extended stay in the region. In September 1861 the Thirteenth Massachusetts Infantry, which had been stationed at Monocacy Junction, received a flag from local women due to “their uniform courtesy and good conduct [which had] so far ingratiated [them] in the good opinion of the neighborhood, that the presentation of a stand of colors was decided upon as a fitting token of esteem.”

began wearing Union aprons: “The bib is studded with stars, the skirt streaked with stripes, and warm, true, brave hearts, beating under all.” A “Union pole” was raised in the spring of 1861 in Middletown to accommodate a flag sewn by the ladies of the town. The women of Westminster presented the local military company with a wreath and bouquets of flowers. Frequently, women of the region gave a hand-sewn flag to soldiers from other states to whom they had grown attached due to the soldiers’ extended stay in the region. In September 1861 the Thirteenth Massachusetts Infantry, which had been stationed at Monocacy Junction, received a flag from local women due to “their uniform courtesy and good conduct [which had] so far ingratiated [them] in the good opinion of the neighborhood, that the presentation of a stand of colors was decided upon as a fitting token of esteem.”

Women not only made flags, they waved them as well. Barbara Fritchie is probably the most famous flag waver of the Civil War, thanks to the poetic rendition of an episode involving her, the flag, and Stonewall Jackson. Regardless of the authenticity of John Greenleaf Whittier’s poem, Barbara Fritchie’s political alignment was not in question among those who remembered her. She was known to express her support stridently for the Union cause throughout the political crises preceding the war, and these sentiments were only intensified by the fighting. It is known that Fritchie stood outside her home and cheered Union General McClellan’s troops as they marched past in September 1862. Whittier’s poem has Fritchie waving a Union flag at Stonewall Jackson’s Confederate soldiers, and Jackson allegedly giving orders to his men not to harm either Fritchie or her flag. This story does not fare well under scrutiny, but the willingness of women to wave flags defiantly in front of enemy troops does.

Women not only made flags, they waved them as well. Barbara Fritchie is probably the most famous flag waver of the Civil War, thanks to the poetic rendition of an episode involving her, the flag, and Stonewall Jackson. Regardless of the authenticity of John Greenleaf Whittier’s poem, Barbara Fritchie’s political alignment was not in question among those who remembered her. She was known to express her support stridently for the Union cause throughout the political crises preceding the war, and these sentiments were only intensified by the fighting. It is known that Fritchie stood outside her home and cheered Union General McClellan’s troops as they marched past in September 1862. Whittier’s poem has Fritchie waving a Union flag at Stonewall Jackson’s Confederate soldiers, and Jackson allegedly giving orders to his men not to harm either Fritchie or her flag. This story does not fare well under scrutiny, but the willingness of women to wave flags defiantly in front of enemy troops does.

Other documented cases of women flag-wavers may have served as inspirations for Whittier’s narrative. Mary Quantrell, a bold and outspoken Unionist, lived only a block away from the Fritchie household. When Confederate forces marched through Frederick, she boldly waved her Union flag in defiance. A Confederate officer requested the flag, and Mary refused, replying that it was “worthy of a better cause than for which General Lee and himself were fighting.”

Nancy Crouse, a seventeen-year-old native of Middletown, was another courageous flag-waver who is reported to have dared to challenge the Confederates. When a group of Confederate soldiers demanded the removal of a large Union flag flown from the Crouse’s home, and no response came, the soldiers resolved to take the flag by force. Nancy Crouse retrieved the flag, wrapped it around herself, and returned to the porch to confront the Confederates with this dramatic gesture. Incensed, one of the soldiers drew his revolver, placing it against Crouse’s head. Crouse stood her ground and declared “You may shoot me, but I will never give up my country’s flag into the hands of traitors!” The soldier demanded twice that she remove the flag and Crouse finally did so, and the soldiers rode away with it. The flag would later be returned to the Crouse family by Union soldiers.

Some women left the flag-waving to others and employed their domestic skills on behalf of the soldiers. On July 4, 1861, the women of Frederick prepared a feast for the First Pennsylvania Volunteers, who were stationed at the state barracks in town. They made or gathered “three thousand pies and tarts, barrels of milk, hams, tongues, chickens, fresh meats, vegitables [sic] and fruits, and other etceteras of good eating, as a token of sympathy for the patriotic cause in which these National defenders are enlisted.”

Even in the domestic sphere, however, war was dangerous. Ginnie Wade (also known as Jennie), a twenty-year old seamstress in Gettysburg, stayed in town during the Battle of Gettysburg to help her sister, who had just had a baby. Ginnie was baking bread for Union soldiers on the third day of fighting when she was killed by a stray bullet. She was the only civilian killed during the three-day battle.

Even in the domestic sphere, however, war was dangerous. Ginnie Wade (also known as Jennie), a twenty-year old seamstress in Gettysburg, stayed in town during the Battle of Gettysburg to help her sister, who had just had a baby. Ginnie was baking bread for Union soldiers on the third day of fighting when she was killed by a stray bullet. She was the only civilian killed during the three-day battle.

With many husbands and sons fighting in the war, some women were forced to find new sources of income. Mary Jane Demus, an African American woman from Mercersburg in Franklin County, was married to a soldier in the 54th Massachusetts Regiment. Pay for African American soldiers was notoriously irregular, so Mary Jane hired herself out to work for others, including husking corn on nearby farms. Her husband, David Demus, took a dim view of this, and in March of 1864, Demus wrote to Mary Jane, “[I] am sorry to think how you hafe to get a long[.] [I] never thot that you [would] hafte to Wark so hard to get a long[.]” A month later, Demus wrote to his wife that he would get paid soon, and he wanted her to stop working outside the home because he knew that “you Cant stande it mutch longer….” Life was tenuous in the best of times for African Americans, and war made life even more difficult.

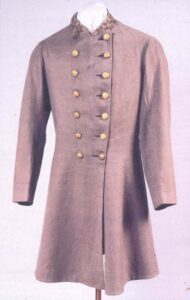

Those women who sympathized with the Southern cause had a more difficult time showing their support of soldiers who joined the Confederate army due to the presence of Union troops beginning in June 1861. While they could not so easily wave Confederate flags or prepare feasts for Confederate troops, as these activities would be viewed as acts of disloyalty, women with southern sympathies were no less committed to their soldiers and the cause for which they fought. Gathering discreetly, “behind closed shutters, they stitched shirts and drawers for their boys.” Jane Claudia Johnson, the wife of Frederick attorney and Confederate General Bradley T. Johnson, went a bit further. She showed her devotion to her husband and the Confederacy by traveling to her native North Carolina to obtain arms for the Maryland troops who had assembled with the Confederate army at Harpers Ferry.

Those women who sympathized with the Southern cause had a more difficult time showing their support of soldiers who joined the Confederate army due to the presence of Union troops beginning in June 1861. While they could not so easily wave Confederate flags or prepare feasts for Confederate troops, as these activities would be viewed as acts of disloyalty, women with southern sympathies were no less committed to their soldiers and the cause for which they fought. Gathering discreetly, “behind closed shutters, they stitched shirts and drawers for their boys.” Jane Claudia Johnson, the wife of Frederick attorney and Confederate General Bradley T. Johnson, went a bit further. She showed her devotion to her husband and the Confederacy by traveling to her native North Carolina to obtain arms for the Maryland troops who had assembled with the Confederate army at Harpers Ferry.

Another instance of a woman, this time from Shepherdstown, aiding the Confederate war effort was chronicled by Catherine Susannah Thomas Markell in the diary she kept during the war years. In an entry on May 26, 1863, Markell told how her friend Ellie Harper, with whom she had gone shopping in Frederick, concealed her purchases when she left the next day. Ellie, Markell said, “left this morning with gray cloth for two soldiers’ suits, a pair of cavalry boots, [and] two pair’s trooper’s gloves … fastened to her hoops!!! She was so heavy we had to push her up the car platform at the depot whither a crowd of us escorted her.” Ellie Harper was taking advantage of the feminine fashions of the day to smuggle gray cloth, boots, and gloves to some Confederate soldiers.

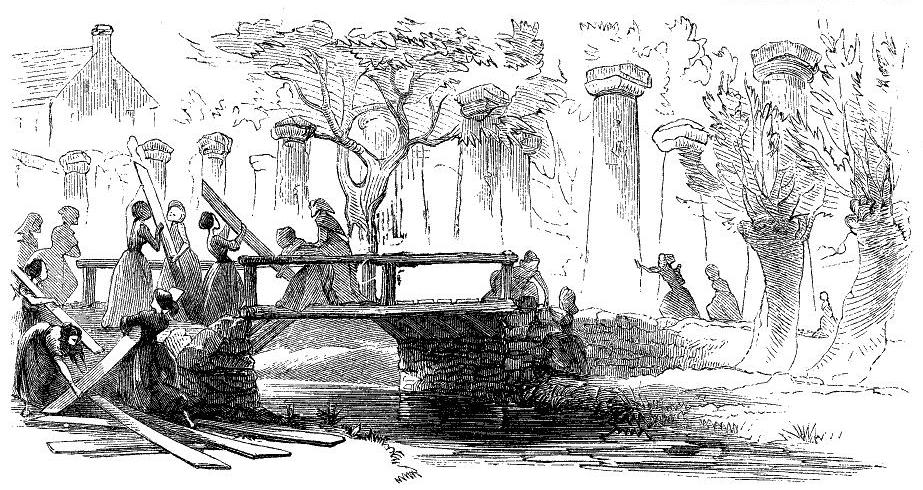

Pro-Union women in Confederate Virginia also took a few risks in expressing their loyalty. On October 1, 1862, Union forces neared Martinsburg, Virginia, which was  in the possession of Confederate defenders. A bridge over a mill-race had been disassembled to block entrance to the town, but as soon as the Union banners were spotted in the distance, women from surrounding houses descended on the bridge and replaced the bridge’s plank flooring to allow the Union troops to cross over. A few hours later, when the Federal soldiers retreated from Martinsburg, the same ladies reappeared to again disassemble the bridge to block Confederate pursuit.

in the possession of Confederate defenders. A bridge over a mill-race had been disassembled to block entrance to the town, but as soon as the Union banners were spotted in the distance, women from surrounding houses descended on the bridge and replaced the bridge’s plank flooring to allow the Union troops to cross over. A few hours later, when the Federal soldiers retreated from Martinsburg, the same ladies reappeared to again disassemble the bridge to block Confederate pursuit.

Ladies’ Relief Associations

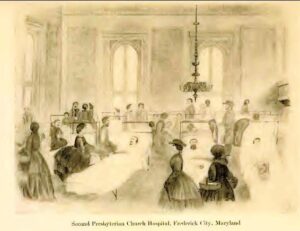

Most towns and communities in mid-Maryland formed relief societies or associations, and women were always in the lead. Here was an opportunity for women to help the war effort by extending their benevolence to the soldiers. In Frederick, the Ladies’ Relief Association was created in August 1861 when fifty women established an organization, elected a president and officers, and formed seven committees (one for each day of the week) with the responsibility for obtaining supplies and articles needed to aid sick soldiers in local hospitals. The women cooked, knitted socks, rolled bandages, and then made daily visits to hospitals to distribute the food, clothing, blankets, and medical supplies. They would also solicit contributions of food and supplies from local citizens and farmers, as they did in October 1861, and then collect and distribute them. And when the number of patients, and the need for supplies, steadily rose over the next six months, in March 1862 the Ladies’ Relief Association published another appeal for assistance: “The number of the sick is great, but let us show that it is not greater than our patriotic benevolence and charity.”

The Frederick women performed their work diligently, so when Dorothea Dix requested that supplies be sent to the military hospital in Frederick because “they need everything,” the Frederick ladies took offense. They informed Dorothea Dix that she was mistaken, that “the wants of the soldiers have been generously provided for by the Ladies’ Relief Association of this city, in all respects” and that they trusted when this information became available to her she would repudiate the “reputation of neglect” that she had cast upon the Frederick group.

The Frederick women performed their work diligently, so when Dorothea Dix requested that supplies be sent to the military hospital in Frederick because “they need everything,” the Frederick ladies took offense. They informed Dorothea Dix that she was mistaken, that “the wants of the soldiers have been generously provided for by the Ladies’ Relief Association of this city, in all respects” and that they trusted when this information became available to her she would repudiate the “reputation of neglect” that she had cast upon the Frederick group.

Carroll County women undertook to provide relief to suffering soldiers after the Battle of Antietam, even though the battlefield was two counties and forty miles away. The women collected two wagon-loads of supplies from local citizens and distributed them to hospitals in Frederick, Middletown, Keedysville, and Sharpsburg. The Westminster American Sentinel praised the Carroll County Ladies’ Relief Association: “Our Union ladies need no eulogy from us, they understand their duty in the time of their country’s trial, and faithfully are they performing it.”

Women in the region also worked with or alongside national organizations, such as the U.S. Christian Commission and the US. Sanitary Commission, formed to minister to the spiritual needs of soldiers and to improve the condition of military camps in order to prevent the spread of disease. In 1864 the women of Clear Spring and Hagerstown held fairs to raise money for both the Christian Commission and the Sanitary Commission. Not to be outdone by the Hagerstown ladies, the women of Frederick also worked to solicit contributions for the Christian Commission in early 1865.

Local newspapers were filled with letters of thanks from soldiers to the women who tended to their needs and lifted their spirits. These serve as testimonials to the contributions of the women’s relief associations. Of the Hagerstown Ladies’ Relief Association, some grateful soldiers wrote: “It was our good fortune to be made the chosen recipients of the patriotic, munificent regard of the ladies of the Union Relief Association of Hagerstown. The vast profusion, variety and excellency of their sweetmeets, &c., which they presented to the rank and file of the 1st Infantry and 1st Cavalry Companies, 4th Regiment Potomac Brigade, Maryland Volunteers, at the Fair Grounds, our head-quarters, on Christmas day, has deeply impressed us all with thankful obligation, which our grateful memories will never forget.”

Camp Followers and Caregivers

Some women wanted to support their causes, and their loved ones, closer to the battlefield. They found ways by following their husbands, sons, and fathers to army camps, or by caring for sick and wounded soldiers in military hospitals. After the battle of Gettysburg, resident Fannie Buehler put it this way: “Our Union men had, with God’s help, driven the enemy back from our homes in the North. It remained for us to do our part as nobly and as well.” In doing their part, some women left, at least temporarily, their private domestic spheres and ventured into places occupied primarily by men.

Camp followers appeared to defy social conventions by entering the male-dominated world of military camps and blurred the lines between the proper spheres for men and women. Yet their activities were framed in ways that allowed them to conform to expected roles. Some wives followed their husbands to wash, cook, and mend their clothing. Some young women followed their beaus. Two young women from Sharpsburg and Hagerstown, Maryland, were discovered in Culpepper Court House, Virginia, in August 1862, accompanying the ammunition train and the signal corps in one of General Pope’s brigades. Their “lovers were enlisted men in the brigade and [they] were sharing the chances of war with them.” The newspaper reporting this “novel scene” pointed out that “had they been dressed in their proper apparel, and been at home under the care of kind mothers, [they] would have been ornaments to their homes.” Entering the world of men was an aberration: “War has some singular matters connected with its varied workings, but none are stranger than this.”

Nursing sick families had always been part of women’s work, but in both the military hospitals and the public buildings that became hospitals in the aftermath of battles, women had been excluded from the male environment of army medical care. Military hospitals employed male nurses, but in June 1861 Dorothea Dix, superintendent of Army nurses, convinced skeptical military officials that women could perform nursing work. As this idea became accepted, Dix put out a call for responsible, matronly volunteers who would not distract the troops or behave in unseemly or unfeminine ways. Dix insisted that her nurses be “past 30 years of age, healthy, plain almost to repulsion in dress and devoid of personal attractions.”

Whether or not the women of the mid-Maryland region met these criteria is uncertain, but it is clear that they played a significant role in providing nursing care to wounded soldiers who flooded the towns and villages after the battles of Antietam, Gettysburg, and Monocacy. Although their names do not appear on hospital staff lists, the shortage of trained male nurses meant that female volunteers with the Ladies’ Relief Associations and the Sanitary Commission often provided care along with supplies. “Quietly, and without any effort to attract the attention of the public,” the women of the region lent “aid to the medical officers.” Benjamin Prather, a Georgian soldier wounded at Antietam, put it simply when testifying to the care he received from local women volunteering as nurses: “The women … are so good to me,” he said. This sentiment was echoed repeatedly.

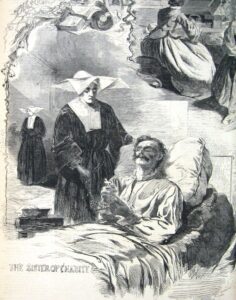

After the battle of Antietam, Daughters of Charity came from Emmitsburg to contribute to the care of the wounded soldiers. The Frederick Examiner reported: “In addition to the other nurses employed inthe U.S.A General Hospital at this city, ten Sisters of Charity from Emmitsburg were applied for, who arrived at the Hospital on Thursday last, and entered upon their duties.— The engagement of these Sisters of Charity, who are schooled to the vocation, is very opportune….” The Sisters were instrumental in helping to establish better patient care, and tended to the needs of both Union and Confederate soldiers. The Daughters of Charity would also travel to Gettysburg in July 1863, where they would be granted permission to care for troops on both sides, enjoying the complete confidence of the provost marshal.

After the battle of Antietam, Daughters of Charity came from Emmitsburg to contribute to the care of the wounded soldiers. The Frederick Examiner reported: “In addition to the other nurses employed inthe U.S.A General Hospital at this city, ten Sisters of Charity from Emmitsburg were applied for, who arrived at the Hospital on Thursday last, and entered upon their duties.— The engagement of these Sisters of Charity, who are schooled to the vocation, is very opportune….” The Sisters were instrumental in helping to establish better patient care, and tended to the needs of both Union and Confederate soldiers. The Daughters of Charity would also travel to Gettysburg in July 1863, where they would be granted permission to care for troops on both sides, enjoying the complete confidence of the provost marshal.

Women Soldiers

Women soldiers in the Civil War were both rare and revolutionary, displaying a spirit and boldness at odds with contemporary views of women’s proper role. By their actions, women soldiers demonstrated that they refused to stay in their socially mandated place. They had to resort to deception in order to achieve their goal of being soldiers, and then they faced not only the enemy’s guns but also the disapproval of society. If a woman aspired to the life of a soldier, she could not at the same time remain a true woman. This did not, however, stop some mid-Maryland women from pursuing the fighting life.

A Frederick woman by the name of Mary Galloway disguised herself as a soldier and set out to join her beau, Lieutenant Harry Barnard of the Third Wisconsin. Mary was wounded at the Battle of Antietam, and was lucky enough to be treated by famed nurse Clara Barton, who soon discovered the soldier’s true identity. Mary returned to Frederick, where she waited for news of her beloved. When a soldier being treated for gangrene from a wound suffered at Antietam spoke of his sweetheart named Mary, an effort was made to locate the girl. The couple were reunited, and later married.

Whether they were making flags or mending soldiers, the vast majority of women on the mid-Maryland border performed domestic tasks associated with the benevolent work traditionally assigned to women – feeding hungry troops, caring for the wounded, continuing to take care of their own families. They did not spend the war in their homes or their cellars, however, and some of the work they were called upon to perform required that they step out of their traditional private sphere. In the absence of their husbands, women took over the masculine duties of running farms and businesses, and in doing so challenged some of the characteristics attributed to nineteenth century women. As they faced the hardships of war and took on tasks formerly reserved for males, the women on the mid-Maryland border changed the role women played in American society, at least temporarily.

Stories in Focus