The citizens of mid-Maryland lived in a crossroads of both political and military action. The location of the nation’s capital meant that Maryland’s loyalty was essential for the Union, and the federal government would take extraordinary, sometimes extra-legal, steps in mid-Maryland to ensure that the loyalties of its citizens would remain with the Union. Citizens in the Confederacy were likewise asked to give up certain civil liberties in the hope that doing so would advance their liberty and security in the future. Civil liberties thus became a casualty of civil war for both the Union and the Confederacy.

The citizens of mid-Maryland lived in a crossroads of both political and military action. The location of the nation’s capital meant that Maryland’s loyalty was essential for the Union, and the federal government would take extraordinary, sometimes extra-legal, steps in mid-Maryland to ensure that the loyalties of its citizens would remain with the Union. Citizens in the Confederacy were likewise asked to give up certain civil liberties in the hope that doing so would advance their liberty and security in the future. Civil liberties thus became a casualty of civil war for both the Union and the Confederacy.

Lincoln, Davis, and Civil Liberties

When Abraham Lincoln took the oath of office on March 4, 1861 to become  the sixteenth president of the United States, the country had literally come apart. Seven Deep South states had left the Union and formed a new nation. Lincoln’s predecessor, James Buchannan, maintained that Lincoln’s election was an insufficient ground for the Southern states’ secession, but he also believed that he lacked constitutional authority to coerce the Southern states to stay in the Union. Over the winter of 1860-61, dozens of proposed compromises, including those by President Buchanan, Senator John Crittenden, as well as a Peace Convention in Washington, D.C., failed to avert a deadly confrontation between the United States and the newly formed Confederate States of America. In his inaugural address, Lincoln observed that “…in contemplation of universal law and of the Constitution, the Union of these States is perpetual. Perpetuity is implied, if not expressed, in the fundamental law of all national governments.” The new president warned that he would not condone this attempt by the Southern states to destroy what the Founding Fathers had created, “You have no oath registered in heaven to destroy the government, while I shall have the most solemn one to ‘preserve, protect, and defend’ it.” Lincoln’s position was clear: he would take whatever steps necessary to keep the Union intact.

the sixteenth president of the United States, the country had literally come apart. Seven Deep South states had left the Union and formed a new nation. Lincoln’s predecessor, James Buchannan, maintained that Lincoln’s election was an insufficient ground for the Southern states’ secession, but he also believed that he lacked constitutional authority to coerce the Southern states to stay in the Union. Over the winter of 1860-61, dozens of proposed compromises, including those by President Buchanan, Senator John Crittenden, as well as a Peace Convention in Washington, D.C., failed to avert a deadly confrontation between the United States and the newly formed Confederate States of America. In his inaugural address, Lincoln observed that “…in contemplation of universal law and of the Constitution, the Union of these States is perpetual. Perpetuity is implied, if not expressed, in the fundamental law of all national governments.” The new president warned that he would not condone this attempt by the Southern states to destroy what the Founding Fathers had created, “You have no oath registered in heaven to destroy the government, while I shall have the most solemn one to ‘preserve, protect, and defend’ it.” Lincoln’s position was clear: he would take whatever steps necessary to keep the Union intact.

With the bombardment and surrender of Fort Sumter in April 1861, Lincoln’s position measurably worsened. The Upper South states of North Carolina, Virginia, Tennessee, and Arkansas left the Union and joined the nascent Confederacy. Maryland, a slave state south of the Mason-Dixon Line but with significant economic and social connections both north and south, remained on the sideline. Because of its geographical location, Lincoln could ill afford to have this key state desert the Union for the Confederacy. To that end, Lincoln and the United States government applied intense pressure, especially during 1861 and 1862, to ensure that Maryland remained a loyal state. Mid-Marylanders felt the strong arm of the Union as President Lincoln issued orders that infringed upon the citizens’ civil liberties. Later in the war, with Maryland secure in the Union, civil liberties violations would continue, but retribution seemed to be the primary motivation.

Meanwhile, in northern Virginia, the Confederacy also engaged in civil liberties’ violations. While the Confederate Congress passed legislation strictly controlling President Jefferson Davis’s exercise of the suspension of habeas corpus and any limitations on freedom of expression, it also passed the Alien Enemies and the Sequestration Acts in August 1861. The former required the deportation of all United States’ citizens living in the Confederacy who were fourteen years and older and who would not declare that they intended to become citizens of the Confederate States, while the latter authorized the seizure of Northern-owned property in retaliation for the United States’ First Confiscation Act. These acts provided justification for private citizens and the Confederate army to impinge directly upon the civil liberties of local inhabitants.

strictly controlling President Jefferson Davis’s exercise of the suspension of habeas corpus and any limitations on freedom of expression, it also passed the Alien Enemies and the Sequestration Acts in August 1861. The former required the deportation of all United States’ citizens living in the Confederacy who were fourteen years and older and who would not declare that they intended to become citizens of the Confederate States, while the latter authorized the seizure of Northern-owned property in retaliation for the United States’ First Confiscation Act. These acts provided justification for private citizens and the Confederate army to impinge directly upon the civil liberties of local inhabitants.

The Legislature Meets in Frederick

Maryland, like other states in the Union and Confederacy during the winter of 1860/61, was divided over its future course. Governor Thomas Hicks had resisted a call by a number of state senators in December 1860 to convene a special session of the legislature to discuss Maryland’s secession from the Union. Events pressed the issue, however. After the fall of Fort Sumter, Lincoln’s call for 75,000 troops, and the attack upon the 4th Massachusetts by Baltimore citizens on April 19, 1861 (known as either the Pratt Street Massacre or the Pratt Street Riot), the governor could no longer prolong the inevitable. With local militias engaged in destroying railroad lines and the City of Baltimore in virtual rebellion, Hicks called for a special session of the legislature to meet in Annapolis on April 26. Union troops occupied the state capital, however, and so the governor redirected the legislature to meet in Frederick on the appointed day. Convening initially at the county courthouse at Courthouse Square, the legislature relocated to what is now known as Kemp Hall on Market Street, a building owned by the local German Evangelical Lutheran Church, where the Senate met on the third floor (or the Red Men’s Hall), and the House, on the second. The legislature heard Governor Hicks recount the turmoil facing Marylanders and the difficulties which lay ahead. He then sent a mixed message for the legislators in their upcoming deliberations. He began, “I honestly and most earnestly entertain the conviction that the only safety of Maryland lies in preserving a neutral position between our brethren of the North and of the South.” The governor then, however, asserted that Maryland should remain in the Union: “I can give you no other counsel than that we should array ourselves for Union and Peace, and thus preserve our soil from being polluted with the blood of brethren. Thus, if war must be between the North and South, we may force the contending parties to transfer the field of battle from our soil, so that our lives and property may be secure.”

Maryland’s geographic reality and deep sectional divisions were not lost on the state legislators. Citing that it lacked the constitutional authority to determine whether the state should secede from the Union, the General Assembly, one day after the occupation of Baltimore by Union troops on May 13, passed Joint Resolution 4 of the Special Session of April 1861, which declared,

The war now waged by the Government of the United States upon the people of the Confederated States, is unconstitutional in its origin, purposes and conduct, repugnant to civilization and sound policy; subversive of the free principles upon which the Federal Union was founded, and certain to result in the hopeless and bloody overthrow of our existing institutions.

While the resolution continued by recognizing Maryland’s loyalty to the Union, it noted that its citizens, “sympathize deeply with their Southern brethren in their noble and manly determination…” and protested against a war “which the Federal Government has declared.” The General Assembly further called for the Legislature to send commissions to both Richmond and Washington, D.C. to consult with Jefferson Davis and Abraham Lincoln, respectively, in an effort to define the relationship between the state and the respective national governments. These efforts came to no avail.

While the resolution continued by recognizing Maryland’s loyalty to the Union, it noted that its citizens, “sympathize deeply with their Southern brethren in their noble and manly determination…” and protested against a war “which the Federal Government has declared.” The General Assembly further called for the Legislature to send commissions to both Richmond and Washington, D.C. to consult with Jefferson Davis and Abraham Lincoln, respectively, in an effort to define the relationship between the state and the respective national governments. These efforts came to no avail.

Throughout the summer of 1861, the federal government took measures to ensure that Maryland would remain in the Union. Federal troops, ensconced in Baltimore, were increased in number and had their positions fortified, while other troops were sent to Frederick. Federal authorities arrested Southern sympathizing leaders in Frederick and throughout the state, including Delegates William Salmon, Thomas Clagett, and Andrew Kessler of Frederick County, Bernard Mills of Carroll County, and State Senator Charles Macgill of Washington County. They would be released only after Maryland’s secession crisis passed. President Lincoln also suspended the writ of habeas corpus, which allowed the federal government to hold citizens indefinitely and without a hearing (see below).

By the time the legislature reconvened in September, with many of its members arrested and troops from Wisconsin stationed in the city, neither the House of Delegate nor the Senate could assemble a quorum. No further debate occurred on the issue of secession. Efforts to secede thus ended in the city of Frederick, successfully subverted and silenced by the Lincoln administration.

Suppressing Speech

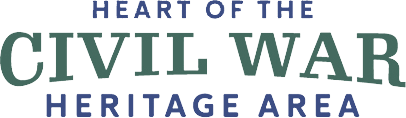

Those in mid-Maryland who supported Confederacy had to be careful of the language they used or face possible repercussions from the government and their Unionist neighbors. Public affirmation of the Confederacy and its leaders could lead to arrest. After William Kelley toasted Jefferson Davis, he was arrested for “treasonable language,” while Richard Warner, of Liberty, met the same fate for giving a cheer for the president of the Confederacy. Three young ladies were arrested in Frederick for singing secessionist songs. Thomas John Claggett, also of Frederick, was arrested and imprisoned for singing “Dixie.”

Desecrating the American flag was an act of symbolic defiance that was certain to elicit condemnation. The Hagerstown Herald of Freedom and Torch Light warned those who chose to demonstrate disrespectful behavior toward the flag that they “should not complain if they are compelled to cast their lot among traitors.” In 1861, when someone “bedaubed [the flag’s] Heaven-born hues with printer’s ink,” the Frederick Examiner concluded that “the villain, who would desecrate the National flag, is capable of any crime.”

Even subtle displays of opposition to the flag could also mark one as a Confederate sympathizer. A Hagerstown paper laid out the rules: “He or she, man or woman, who passes into the street, or sidles to the edge of a pavement, to avoid walking under the American flag, offers to the Government an indirect insult, and affords unmistakable evidence of disloyalty. Instances of this kind are said to have occurred in our own town, but those guilty of such treasonable conduct, whether male or female, if they persist in it, may get themselves into trouble before they are aware of it.”

Waving, or wearing, the Confederate flag was an overt demonstration of support for the Confederacy. Ulysses Hobbes was arrested at Monocacy Junction on July 28, 1862 for “a display of treasonable opinions.” Specifically, when an acquaintance produced a small Confederate flag, Hobbes indicated that he “was not afraid or ashamed to wear it,” pinned it to his chest, and subsequently blurted “some bombastic expressions.” At this point, Hobbes was ordered to surrender the flag, but refused. Captain Yellott, the arresting officer, offered this Confederate sympathizer his release upon taking the oath of allegiance. Hobbes refused and was transported to a Baltimore jail.

On a few occasions, those in possession of a Confederate flag avoided punishment. In June 1861 soldiers of a Rhode Island regiment, upon entering John Hagan’s tavern, located “at the [Braddock] mountain, and seeing a Secession flag there, seized it.” Hagan chose to report instead the theft of a gold watch, a charge that was described in a lively account printed in The Frederick Herald. When a number of the Union officers “went to the Herald office to demand an explanation for a scurrilous article in that journal… some one (sic) cried out there was a Secession flag in the office.” The flag, “it is said, was spirited away out of the back window.” No action was taken against Hagan.

Citizens in northern Virginia also faced the threat of repercussions if their voices dissented from the majority’s. In Waterford, Virginia Mollie Dutton, a Quaker, confirmed this in a letter to her friend in March 1862:

Oh! These Virginians, worse by far than the South Carolinians themselves – and the Mississipian (sic) soldiers have expressed astonishment at their behavior.They come they say to protect and do nothing but destroy. Oh! Deliver me form this Southern Confederacy! We are the sorriest slaves that ever trod the earth. To talk is Treason. To act,Rebellion, our every movement watched the vilest set – mean,contemptible men.

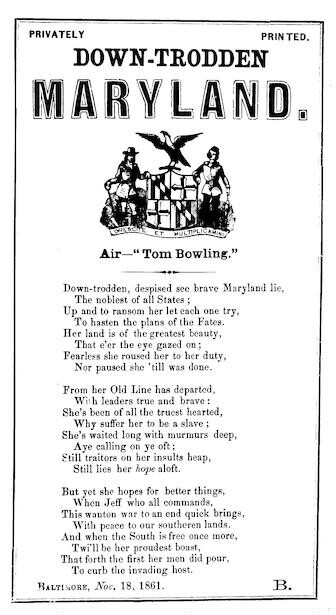

During the Virginia secession crisis, Union supporters were under constant pressure to conform: “Any dissent, even the attempt to change the direction at the ballot box, was treason.” Some who voted against the secession ordinance “had to face charges and endure loyalty hearings.”

Closing Newspapers

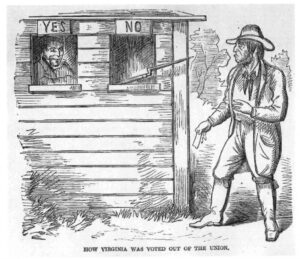

Freedom of speech also extends to newspapers, and suppression of the press became a controversial issue during the Civil War. Washington, Frederick, and Carroll counties all had certain newspapers which endorsed the Union cause and others that supported the Confederacy. John A. Dix, commander of the Maryland Department for the Union, advised one Unionist in favor of closing “secessionist presses” in Baltimore that “There is no doubt that a majority of the Union men … (who) desire the suppression of all the opposition presses … but there are many – and among them some of the most discreet – who think differently.” Despite the initial reluctance of the government to censor the press, the Southern sympathizing presses were eventually shut down by the government, some permanently and others to resume publication after the termination of hostilities.

In the early stages of the war, many Southern supporting papers were forbidden to use the mail service to deliver the papers. In February, 1862, postmaster W.D. Jenks, “received an order from the Post Master General, directing [him] not to receive or mail the [pro-Confederate] Republican Citizen until otherwise ordered.” This had a negative impact on readership, and placed severe financial strain on the publication. Ultimately, the Citizen’s operations were suspended in 1862.

As the war progressed, the Southern supporting presses in the region were faced with increasing pressure from the government. The Free Press, a weekly publication originating in Williamsport, began publication on October 31, 1862, but suspended publication from 1863 to April 1866. Publisher A.G. Boyd was arrested on March 12, 1863 for printing “a ‘copperhead’ concern,” according to its Unionist rival, the Herald of Freedom & Torch Light, “and subsist[ing] upon the rewards of its envenomed opposition to the Union cause.” To ward off any allegations of partisanship or bias, the Unionist Herald of Freedom & Torch Light proclaimed, “We understand that it has been insinuated in rebel circles that this proceeding was instigated for our personal benefit, [but] we have never advised any interference with their venomous sheets, nor do we desire, or would we intrique (sic) to obtain one cent’s worth of their patronage.” Boyd was banished to the Confederacy. Another newspaper forced to terminate publication in 1861 was the Frederick Herald, which had supported John C. Breckinridge in the election of 1860 and the Confederacy after its formation.

As the war progressed, the Southern supporting presses in the region were faced with increasing pressure from the government. The Free Press, a weekly publication originating in Williamsport, began publication on October 31, 1862, but suspended publication from 1863 to April 1866. Publisher A.G. Boyd was arrested on March 12, 1863 for printing “a ‘copperhead’ concern,” according to its Unionist rival, the Herald of Freedom & Torch Light, “and subsist[ing] upon the rewards of its envenomed opposition to the Union cause.” To ward off any allegations of partisanship or bias, the Unionist Herald of Freedom & Torch Light proclaimed, “We understand that it has been insinuated in rebel circles that this proceeding was instigated for our personal benefit, [but] we have never advised any interference with their venomous sheets, nor do we desire, or would we intrique (sic) to obtain one cent’s worth of their patronage.” Boyd was banished to the Confederacy. Another newspaper forced to terminate publication in 1861 was the Frederick Herald, which had supported John C. Breckinridge in the election of 1860 and the Confederacy after its formation.

In some instances, the government did not need to actively intervene to stop publication of a “copperhead” paper; it could rely upon the actions of an angry public. While the government briefly incarcerated the Hagerstown Mail’s editor, Daniel Dechert, in 1862, an angry mob ransacked the paper’s office during the evening of May 24, 1862 and destroyed the presses and type, which were then scattered over the public square. The Mail was forced to suspend its publication for eighteen months. Likewise, on evening of April 15, 1865, after the assassination of President Lincoln, a group of citizens met at the courthouse in Westminster and passed a resolution condemning the Western Maryland Democrat for its criticisms of the late president. After midnight, a mob stormed the newspapers offices, destroying the type, machinery, and paper, and, reportedly, hanging the editor of the paper, Joseph Shaw.

Suspension of the Writ of Habeas Corpus

The writ of habeas corpus requires the official responsible for the incarceration to produce the petitioner in open court so a judge may determine the legality of the imprisonment. Chief Justice Salmon P. Chase, in Ex parte Yerger, observed in 1869 that the writ has been “esteemed the best and only sufficient defense of personal freedom.” If the writ is suspended, one can be detained indefinitely without appearing in court. The Constitution allows for the suspension of the writ of habeas corpus “… when in cases of rebellion or invasion the public safety may require it.”

In the spring of 1861, President Lincoln was keenly aware of both the precarious loyalty of Maryland and the continued guerilla activities in the state that were inhibiting federal troops from reaching Washington, D.C. On April 27, he ordered the military authorities to suspend the writ of habeas corpus along the Philadelphia-Washington, D.C. corridor. With the federal seizure on May 25 of John Merryman, a well-known Baltimore County Confederate sympathizer, the constitutionality of the suspension of the writ was challenged. Chief Justice of the Supreme Court, Frederick’s Roger Brooke Taney, sitting as judge on the federal circuit court for Maryland, held in Ex parte Merryman that Congress, not the president, possessed the authority to suspend the writ of habeas corpus. Lincoln chose to ignore the opinion, defending his action as the result of “…popular demand, and a public necessity.”

In the spring of 1861, President Lincoln was keenly aware of both the precarious loyalty of Maryland and the continued guerilla activities in the state that were inhibiting federal troops from reaching Washington, D.C. On April 27, he ordered the military authorities to suspend the writ of habeas corpus along the Philadelphia-Washington, D.C. corridor. With the federal seizure on May 25 of John Merryman, a well-known Baltimore County Confederate sympathizer, the constitutionality of the suspension of the writ was challenged. Chief Justice of the Supreme Court, Frederick’s Roger Brooke Taney, sitting as judge on the federal circuit court for Maryland, held in Ex parte Merryman that Congress, not the president, possessed the authority to suspend the writ of habeas corpus. Lincoln chose to ignore the opinion, defending his action as the result of “…popular demand, and a public necessity.”

In mid-Maryland, federal authorities used the suspension of the writ to exert authority over those not only in direct opposition to the federal coercion necessary to maintain Maryland in the Union, but also against those who expressed sympathy for the Confederacy. The most egregious example of the former was the arrest of three legislators from Frederick County and one representing Carroll County because of federal authorities’ fear that they would support a secession ordinance. Once Maryland was securely in the Union camp, the men were released.

Far more numerous were instances involving individuals held for their known Southern sympathies. John Baughman, editor of the Republican Citizen, was arrested at Sandy Hook on July 12, 1861 on the charge of treason. He had letters addressed to Bradley T. Johnson, then a Confederate major from Frederick. Among other evidence against Baughman was that “he has been in the habit of visiting Sandy Hook frequently, under the pretext of looking after his papers mailed to Virginia; but in reality, as was suspected, to convey information to the rebels.” Typical of these types of cases, Baughman was released within days after taking the oath of allegiance.

Exile

The most extreme punishment implemented by the Union was the exile of civilians who demonstrated public support for the Confederacy. Deportation of citizens who have opposed the government during wartime is not constitutionally authorized, and has been utilized sparingly in our country’s history.

While imprisonment or shutting down one’s business were the usual consequence for those exhibiting public support for the Confederacy, General Robert C. Schenck, commander of the VIII Corps, also employed banishment to remove those charged with disloyalty to the Union. In the spring of 1863, Richard D. Poole of Liberty and John S. Lynch of Baltimore were arrested at Westminster and exiled, because they “profanely called upon the Most High to d—n the Yankees.” This was not an isolated incidence of banishment by General Schenck. In March 1863, A.G. Boyd, publisher of the Maryland Free Press in Washington County, was arrested and “taken off, it is said, for the purpose of being sent beyond the Federal lines.” On July 30, 1864, the Daily National Intelligencer in Washington, D.C. reported that the Republican Citizen had been shut down, with its editors, Baughman and Norris, banished south of the Potomac River. Baughman’s wife and three children were sent to the “Senandoah [sic?] Valley of Virginia alone, entirely isolated from her friends….” Upon taking the oath of allegiance, Norris was permitted to return.

Perhaps the most far-reaching implementation of this policy occurred in the summer of 1864. In mid-July, Major John I. Yellott, Provost Marshal for Frederick County, complained to General David Hunter, commander of the Department of West Virginia, which included the counties in western Maryland, that local Confederate sympathizers in the county identified the property of Union men to the Confederates who had occupied Frederick prior to the Battle of Monocacy. The Provost Marshal sought guidance on an appropriate federal response. Hunter ordered the immediate arrest of all persons known, or suspected, of having engaged in such behavior. Also to be arrested were the suspect’s families as well. The men were to be taken to a federal prison in Wheeling, West Virginia, while the families were to be deported behind Confederate lines. In addition, their homes and furniture were to be seized, with the proceeds from the sale of the furniture at a public auction to be used “for the benefit of Union citizens of the town who are known to have suffered loss of property from information given by these persons.”

To avoid these consequences, male citizens in Frederick City and that portion of Frederick County falling within the purview of the Department of West Virginia were required to appear at the Provost Marshal’s Office between 8:00 a.m. and 5:00 p.m. to swear an oath of allegiance to the United States.

To avoid these consequences, male citizens in Frederick City and that portion of Frederick County falling within the purview of the Department of West Virginia were required to appear at the Provost Marshal’s Office between 8:00 a.m. and 5:00 p.m. to swear an oath of allegiance to the United States.

By August 1, twenty-three southern sympathizers and their families had been marked by Hunter for arrest and banishment, including James M. Schley, George Potts, Sr., Dr. Robert Johnson, William Wootten, and F.H. McGill. While the Frederick Examiner supported Hunter’s policy, others were adamant that Hunter’s policy would result in more harm than good. George R. Dennis, a lieutenant colonel in the 1st Maryland, wrote to the Lincoln administration on behalf of “a large number of prominent Union Citizens of Frederick.” In his letter, Dennis referred Lincoln to the “horror at [the guerrilla warfare in] Missouri,” stating that Fredericktonians wished “to avoid the unhappy state of her citizens,” and requested that the President “interpose his authority, and modify, or have the order revoked.” Likewise, Francis Thomas, a former governor of Maryland and member of the House of Representatives during the Civil War, advised that “Major Yellott, selected for arrest, such persons a Union man pointed out.” He concluded, “This wholesale proceeding, seems to me, madness and folly…. The arrest of quiet, inoffensive citizens, who have not, publicly, given, by words, or acts of encouragement to the enemy, cannot but be mischievous.”

In his defense, Hunter argued that those arrested and ordered beyond the federal lines were identified “to me by the loyal citizens of good standing as dangerous persons, sympathizers with the rebellion, who have by all means in their power aided and abetted the rebel cause, communicating habitually with the enemy across our lines, giving military information, denouncing loyal citizens on the advent of rebel raiders, and otherwise giving moral and material aid to the rebel cause.” He concluded, “It is impossible for me to conduct military operations advantageously in this department if these spies and traitors are permitted to go at large and continue their disloyal practices in the midst of my army.”

Hunter’s defense did not sufficiently outweigh the harm which banishment would have caused. Lincoln directed that “the Secretary of War will suspend the order of General Hunter … until further orders, and direct him to send to the Department a brief report of what is known against each one proposed to be dealt with.” As a result, Hunter requested that he be relieved of command. He was granted a leave of absence on August 8 and was relieved of command approximately three weeks later. This suggests that there were limits to President Lincoln’s willingness to violate civil liberties. By 1864, when a Union victory seemed assured, Hunter’s orders went farther than Lincoln felt was necessary.

Seizure of Property

Even prior to the passage of the Sequestration Act during the summer of 1861, Confederate and local authorizes were active confiscating the property of pro-Union citizens. In Leesburg, Confederates scrutinized poll lists in order to “identify everyone who had voted against secession.” Those who had “were the first have farms, horses, wagons, and forage taken by the Confederates.” A magistrate in Lovettsville wrote to Governor John M. Letcher, objecting that the Southern soldiers were “’taking by impressments and otherwise, the property of our people, in an illegal and rebellious manner, leaving in some cases our citizens almost without the necessities of life, and without horses, thus depriving them of the means for making a living.’” The property of Unionists living in Loudon County was, apparently, at a high risk of being seized.

For those in the Union, however, confiscating property of Southern supporters presented a thorny problem, as the North’s position was that Southerners were not enemy aliens but rebellious U.S. citizens. Despite grave reservations, Lincoln signed the Second Confiscation Act, passed by Congress in 1862, which allowed for the seizure of property of Confederate military officers, Confederate public officers, persons who took an oath of allegiance to the Confederacy, or any person giving aid or support to the Confederacy. This included the immediate liberation of slaves of disloyal owners. Confederate General Bradley T. Johnson of Frederick had his property confiscated, and his home became the headquarters of Union General Nathaniel Banks.

Conclusion

From the Civil War to the present, attention has focused on whether the Lincoln administration violated citizens’ civil rights or acted appropriately in a time of crisis to preserve the Union. Americans were confronted with difficult choices at a time when upholding certain civil liberties could jeopardize the existence of the Union. Yet, should the government be able to destroy the very thing it is trying to preserve? In mid-Maryland, violations of civil liberties occurred, ranging from arrests for singing “Dixie” to arrests of state legislators in order to prevent a quorum from voting on secession. The latter was nothing less than interference with the legislative process of the democratic republic. President Lincoln’s understanding of constitutionalism within the context of a perpetual union permitted him to act in the first years of the War with considerable latitude regarding citizens’ civil liberties during America’s greatest constitutional crisis. Once the crisis receded, Lincoln rescinded orders in the field that violated civil liberties. As president, Lincoln infringed upon the citizens’ civil liberties to a degree commensurate with the crisis confronting the Union. President Davis was likewise committed to the survival of his country, and would sacrifice civil liberties to preserve the Confederacy.

Stories in Focus